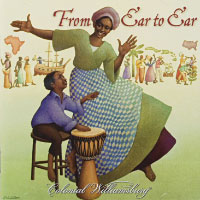

Emily James talks about the music of Africa performed on a new Colonial Williamsburg recording.

Podcast (audio): Download (2.8MB)

Subscribe: RSS

Transcript

Lloyd Dobyns: Hi! Welcome to Colonial Williamsburg: Past & Present on history.org. This is “Behind the Scenes,” where you will meet the people who work here. That’s my job. I’m Lloyd Dobyns, and mostly I ask questions. This time, I’m asking Emily James, who is involved with a new music project, so the first question is obvious –what is the new music project?

Emily James: Well, the new music project is a CD. Larry Earl and Abigail Schumann and Chuck [Smith] and several others have been involved with a CD. When Larry first approached me about the CD, I was of course excited. He talks about a CD that would have a backdrop of the Middle or Trans Atlantic [slave trade], and talks about doing some African songs, and British West Indian songs, and then some North American songs much like some that would be done on the Sea Islands of Georgia. For me, I had two that I am the leader of those two – the call and response, and I am very excited about it.

Lloyd: Call and response? There is a lead singer and then everybody else answers?

Emily: That is correct. It’s a way also…it’s an African tradition, also religious belief – you call and you respond. But “call and response” is popularly known as a field song. You’re in the fields. It’s a way to regulate, and to pace, and to slow the work down, while sometime masters – if you look in a book called The Black Family in Slavery and Freedom by Herbert Gutman. Masters are tapping their feet to the beat of the music want you to speed up, but you aren’t going much faster. Because there are quotas to be met, and if you cannot, or if this gang cannot meet their quota, then they would be disciplined, most often whipped. So therefore you have a hollerer, or a shouter, that shouts some words out, and then you have the group that would respond. So, when you raise the hoe up, everybody would raise the hoe up at the same time, and then you take it down, and each row would be completed at the same time.For instance, one of the music on the CD, and this is from Jamaica, the British West Indies, most often sometimes the maroons, which would have been slaves that took to the hills and refused to be slaves, and they formed their own community.

(Sings) “Bring me half a hoe, run come gimme ya,” and the response would be “Bring me half a hoe, come gimme ya.” “Busha want me figa dig up pitata. Bring me half a hoe, run come gimme ya.” So he’s pumping his feet to the beat of the music. He’s entering in his diary; “It’s increasingly hot, and you can hear my Negroes singing from sunup until sundown,” not realizing they are regulating, they are pacing the work; they’re slowing it down, and most often sometimes they can be singing about the master. You’re singing about a buzzard, then quite naturally it would have been the master you’re referring to if the master is approaching, then you carry the tempo faster, or if he’s not,

then it’s slower.

Lloyd: (Laughs)

Emily: So therefore you are mimicking him, with him not realizing, and he’s writing in his diary – and that’s what you are reading today, how these Negroes were happy; you can hear them singing from sunup to sundown, but when they are singing, maybe they may be refer to his wife as Emma.

(Sings) “Hoe, Emma, hoe, hoe Emma, hoe. You turn around, dig a hole in the ground. Hoe Emma, hoe. Emma, you’ve got a great big foot.” And then the response: “Hoe Emma, hoe. You turn around, dig a hole in the ground. Hoe Emma, hoe. With foot that big, you shouldn’t be married,” and the response: “Hoe, Emma, hoe. You turn around, dig a hole in the ground. Hoe, Emma, hoe.” So, we make you believe we’re happy, not realizing we’re surviving…

Lloyd: …all these happy slaves are just making fun of you.

Emily: That is correct.

Lloyd: So all these songs have something to do with slavery at the time.

Emily: Some meaning. That is correct. Or, you’ll hear the children. Because most often we forget about the children, but as a parent [today] we send our children to school to give them a skill to later on survive in life. So, before you send these children [of slavery] in the field, you’re going to be singing, and you’re going to have them singing songs or playing games to regulate and to pace the work. “Mama, why do we have to be slaves?” You may sing a little song to them to show you how to survive. One such song we have on the CD is (sings) “Juba this and Juba that, Juba this and Juba that, Juba kill the yellow cat. Juba kill the yellow cat. Bend over double trouble, Juba; bend over double trouble, Juba, ha-ha, Juba.” Meaning the yellow cat would be the master. Bending over is probably a stomach ache. Why did mama do that? (Sings) “You bake the bread, you bake the bread, and you give us the crust, and you give us the crust. You cook the meat, you cook the meat, and you give us the skin, and you give us the skin. And that’s when my mama’s trouble began. I say Juba. Juba.” It’s a call and response, and it’s a patting game. (Claps) The children are patting, but basically teaching them how to survive, letting them know never let the master know how you think. Always have a face for the master: “Yes, sir, yes, sir, thank you, sir.” But then behind the master … or you have to have a face, and therefore you may read documentation about slaves always wearing a mask, and those are the masks we’re referring to…so you have to teach these children how to survive. Never let the master know how you feel. Keep your mouth shut, your eyes and ears open. That’s how you learn, so it’s a way to survive.

Lloyd: Where did you learn this, because clearly you were never a slave, so that’s out.

Emily: (Laughs) Well, you know, you read, and when you read to give justice to these people’s lives, you try to become this individual. And again, these are lessons, these are stories worth telling. This is American history; this is becoming an American, and I try to do justice to each and every character. My favorite character was one…because some of these characters…we’ll go to a museum, because most museums tap into Colonial Williamsburg [expertise], because we have been telling this story [of slavery] for many years. And when we go to do workshop; I remember doing a workshop at London Town House and Gardens in Maryland. I just had two words, maybe two lines, on a woman that had become crazy. And, you have to go back to the antebellum period and look at what’s happening during that period to tell the story. Why would she end up mad? Could she have had children that were sold off based upon the time period? That’s one of the most memorable characters I have done, because from that character, we booked that same night, we booked one program for Anne Arundel College, from the program I did, another one to the Frontier Museum, and then back to London Town. So that one night, it was so powerful that we booked three to four programs that one night. So, it’s a memorable character – and I love them all.

Lloyd: How do you keep up with the differences – 16 different characters?

Emily: Well, I read a lot, I love reading, and my library is probably half of this room, and in all my travels, I buy books and not only books on slavery, but I can talk about Benjamin Rush; I can talk about Benjamin Franklin, because you have to know about the oppressor to accurately tell the story of the enslaved. I just love to read a lot. My daddy was very strict, and so therefore we didn’t have Nintendos, I buried myself in books, and I love reading, and I am able to keep up with my characters in the Revolutionary City. I have two – Hannah at Carter’s Grove, and Flora at the Raleigh Tavern.

Lloyd: Well, do you think they’ll be fun? Do you think people will enjoy them?

Emily: My characters?

Lloyd: Yes.

Emily: Not only will these characters be fun, but the Revolutionary City is the best thing since sliced bread. I don’t like to put my name on a product if it’s not good, and I’m a part of the Revolutionary City.

Lloyd: Going to have any singing role?

Emily: I can, as I go about my daily duties, because these people were singing people.

Lloyd: It’s a shame to know as much about singing and do it as well as you do and not incorporate it in what you do.

Emily: To engage the guests, I can, because they are also religious songs. Most of these enslaved people were taught to read from the Book of Common Prayer, and from the Bible, and therefore, we know several 18th-century songs like “Amazing Grace” that John Newton had written. He’s a slave ship captain.

Lloyd: First mate and then captain…I know him.

Emily: Good…You’ve heard of him…then there are several other songs that I can do to also engage the audience, and then I may tell them my story. Hannah is a slave in the house at Carter’s Grove, and I talk about her being banished to the fields, and I’ll be wearing my gown to tell them how I feel with master actually taking me now to send me out into the fields to till the soil, for God’s sake, what is he thinking about? So, I’ll be able to tell my story in various ways, but in a proud and dignified way, not that I like it, but how I survive it.

Lloyd: That’s Colonial Williamsburg: Past & Present this time. Check history.org often. We’ll post more for you to download and hear.