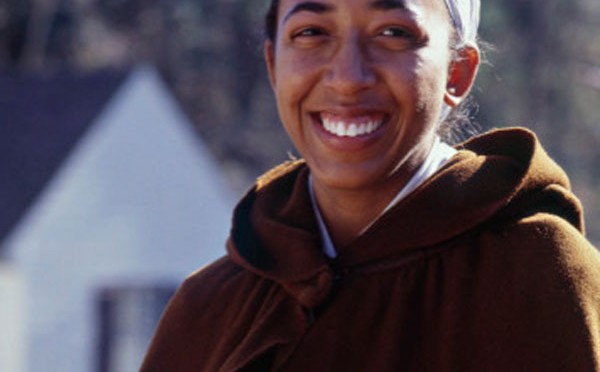

Hope Smith talks about the women and children who followed their men to war.

Podcast (audio): Download (3.1MB)

Subscribe: RSS

Transcript

Lloyd Dobyns: Hi! Welcome to Colonial Williamsburg: Past & Present. We’re on location today to talk about the contributions of enslaved and free blacks to the American Revolution. Colonial Williamsburg this October celebrates “Brothers in Arms” with a weekend of 18th-century military encampments, demonstrations, and character interpretations. I’m Lloyd Dobyns on history.org. Today I’m talking with Hope Smith about black women who followed the British army, hoping to find their freedom.

Lloyd Dobyns: When Lord Dunmore issued his proclamation, it asked for able-bodied men, and about half the blacks who went to him were women and children. How come?

Hope Smith: Well, actually, the proclamation states that indentured servants, slaves owned by rebels willing and able to bear arms, so he doesn’t explicitly say “men only,” he does want men to add to the soldiers that he has already, but also by having women and children leave their masters, it is disrupting your enemy and how they make their living. And for these enslaved individuals themselves, they’ve heard the rhetoric of the revolution for years now, where they’ve heard wealthy white men comparing themselves to slaves, so when this offer of freedom comes about, a lot of them are making the decision to secure some freedom themselves.

Lloyd: So all the talk of freedom actually for the slaveholders was sort of a double-edged sword. You’ve planted the idea.

Hope: Absolutely.

Lloyd: Okay, so you go to the British camp. What do women do? I mean, you’re not carrying a musket. That’s out.

Hope: A lot of the same things that they would have been doing on their properties. You have women who are nurses; you have women who are cooks; you have women who are laundresses, seamstresses. Children, depending upon their age and size, might be doing some of the day laboring, jobber work, looking for wood, that type of thing. So, the labor doesn’t really change. The conditions are going to be difficult for everybody – white or black, free or enslaved – who joins with Lord Dunmore’s troops. But the labor is going to be pretty much the same as what they were doing on their home properties. The choice is what’s different.

Lloyd: It makes sense in one way; in another way, you’re sort of curious about why you are running away to do the same kind of work and just as much of it under worse circumstances…

Hope: I think it is the choice. There is the Revolutionary War, but then there is the revolution on a lot of different fronts. And, a lot of the ideas that these enslaved blacks are hearing – you know, whites talking about them being slaves, or them being in chains or in bondage to England… the irony, you know, was not lost on them – not just during the time of the war but before the time of the war.

I think the difference as opposed to people running away or maybe smaller scale insurrections is that this proclamation is essentially the backing by the mother country – the king’s representative in the colony – and then Lord Dunmore’s proclamation, within two to three years, becomes applicable to all the colonies. So slaves from all colonies who run to the British can receive their freedom. So it’s a little bit different this time – not to say that they trust the British, or that the British are doing it because they are benevolent, but it’s legal backing from the British government that you can secure your freedom by helping them deny the freedom that your oppressors are fighting for.

Lloyd: How did it turn out?

Hope: Well, the British…lost.

Lloyd: Lost…makes a lot of difference.

Hope: When you look at these blacks that are leaving, as opposed to – on the Continental side especially – white soldiers, you are fighting usually for a period of time. But it’s the duration of the war. So, you have these camp conditions which are going to be difficult, when there are shortages of food or medicine. Food and medicine is going to be given to those that are soldiers first. So, you might find yourself going without food, with [out] medicine if you are sick.

Speaking of medicine, one thing that happens when you have all these people, and especially [traveling] with the British army, is you see smallpox devastating the population as they are traveling together, and that’s something that you see happening at the last decisive battle. Yorktown is where slaves are turned out because of that – shortages of food and sicknesses and illness. It is still about a two-year time period where the war ends so much, technically with the battle of Yorktown, and the British troops evacuate. So you see a lot of blacks, especially in New York, but then you see about 15,000 blacks having to evacuate now the United States, not colonies, if they wanted to receive their freedom.

So, even though it’s estimated that about 50,000 to 55,000 ran during the war, only a small percentage will actually leave to get that freedom, because that means leaving behind family members. And, for most of those individuals, they’re going back maybe two, or four, or five generations being born in this country, so it becomes very difficult. So those blacks will evacuate to Halifax, Nova Scotia…

Lloyd: …not exactly home country…

Hope: …not exactly home country….Some to England, some will go with Lord Dunmore, that Virginia governor, who will then govern the Bahamas, which is not as glamorous as it sounds today – very rough, very difficult conditions at that time. Some will eventually go on to settle off the West Coast of Africa in Sierra Leone, but it’s leaving the country, leaving home and family…

Lloyd: I just read about Sierra Leone the other day…when it was opened up as a home for past slaves – that was not a very nice place.

Hope: Very difficult. Very difficult conditions, and, again, for most of these former slaves, the colony where you were born, your family is going back several generations, so in turn, you are going in to a strange land, so it is not going “back to,” but you are going “into” a strange land, and the conditions are very difficult – the land, the climate, the work, you have to get used to that – and there are already groups of people living there, so kind of comparing it to what happens in these different colonies is the English are coming here.

Lloyd: Slaves, American slaves would no more fit into Sierra Leone than they would Nova Scotia, and the people who were there certainly would not have welcomed you.

Hope: Not really, not really, and in turn, like I said, I kind of think about how it was as the English were coming into these colonies with native Americans here, very different but on a different scale comparing it to these now blacks that are coming from these colonies settling in Sierra Leone.

Lloyd: For the ones who didn’t go to Nova Scotia and didn’t go to the Bahamas with Lord Dunmore, what happened to the slaves who had taken the chance for freedom and either got turned out because of sickness or because the British lost?

Hope: Very early on, you actually see “a window” offered where slaves who ran to the British can return to their masters without fear of punishment. That is right after the proclamation is issued, so it is giving them a period – I don’t think it is anything longer than a month – but for a couple of weeks, and it’s propaganda on both sides, so it is probably a lot of exaggeration on both sides. But for those that returned, there was no punishment. But for those who were captured after that, you see some being sold – as well as white loyalists, as well, indentured and free white loyalists – sent to the lead mines in the western part of the colony here; you see some maybe being sent to the sugar islands; you see some jailed for their beliefs or for wanting to follow the British.

You see, believe it or not, a small group of blacks after the war that managed to live as maroons almost, comparable to maroons in Jamaica, but in Georgia, the western part of Florida, off the Mississippi; they don’t want to leave, but they still want their freedom. So, they, this small group of people, managed to do that for maybe 15 to 20 years, but by the early 1800s, they are all either dead or recaptured. And then for those who are returned to their owners, how an owner punishes slaves is something they can decide, it is not decided by the law. And another thing is that those slaves that do leave, their family that remains behind may also be punished in different ways. By the time they are returned to that property, that family member may have been sold or sent elsewhere.

Lloyd: Were the lead mines as bad as they sound like they would have been?

Hope: Awful. Awful. A lot of times, before the war, being sent to the sugar islands was looked at as a slow death sentence, where, because of the intensity of the work – and the work is intense whether it is tobacco plantation, laundress, what have you – but the 24/seven work was a slow death sentence where you are dying probably within three to five years if you are sent there. I would say it’s about the same in the lead mines, maybe less than that.

Lloyd: Generally, unless I’ve got this all wrong, it did not turn out well for most of the people who ran to Lord Dunmore, but if they hadn’t run, it also wouldn’t turn out well.

Hope: Absolutely, you are absolutely right. I think it is that choice and being able to make the decision to run, and while you are running, being able to make the decision to stay. And, why you are staying, it might not have anything to do with an owner, or how an owner feels in his beliefs, but family considerations, and you are absolutely right. The most change is for that small group of wealthy white men at the top, after the Revolutionary War, but for everybody else, it’s happening in increments up until the 20th century!

Lloyd: I keep thinking, the two percent of white men at the top – it was about two percent – maybe something else…

Hope: …about two percent.

Lloyd: The Revolutionary War for everybody else was a loser. It just was.

Hope: Absolutely, you see some movement of the very upper, upper of the middling sort. So, before the Revolutionary War, you might have a wealthy tavern keeper – who is not going to be considered a gentleman because he was not born into the wealth – you might see his participation in government increase, but for other individuals, you know if that person who owned property or was a tradesman was black, you don’t see that happening for him.

Lloyd: “Brothers in Arms” is October 8th and 9th. For more information, check history.org, where you’ll also find more to download and hear. That’s Colonial Williamsburg: Past & Present this time. Hope you enjoyed it.