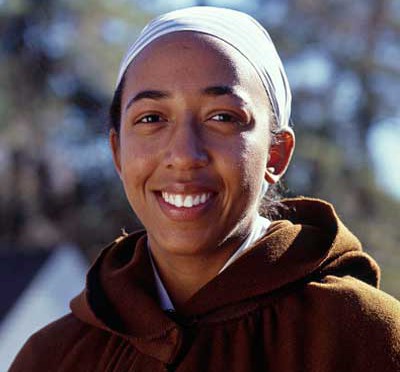

Independence was a promise extended to landed white men only. Historic interpreter Hope Smith lays out a slave’s perspective on freedom.

Podcast (audio): Download (4.0MB)

Subscribe: RSS

Transcript

Lloyd Dobyns: Hi! Welcome to Colonial Williamsburg: Past & Present on history.org.

Today I'm with Hope Smith, and at Colonial Williamsburg, she interprets Eve, a skilled and valued slave in the Peyton Randolph household. Portraying Eve, she'll describe what the prospect of independence meant to Williamsburg's enslaved population. Did it have any meaning, really?

Eve: Well, not as I can see yet, sir. This independency will only affect the gentlemen most. It will not even affect most of the citizens in this colony. It will not change things for men that are not propertied, even if they are white. It will not change things for Negroes that are already free. And it most certainly will not change things for them that are slaves. It only states that these 13 colonies will no longer be colonies at all to England, but that they will become 13 separate countries. It seems as though they are going forward still with slavery as a part of it.

Lloyd: That being the case, do you have any particular feelings about being independent from Great Britain, or not being independent from Great Britain?

Eve: Well, I cannot say. There were rumors as far back as before I was born that when Governor Gooch came, there were going to be changes for the Negroes, that those in England had problems with the treatment of some of the slaves, or even them that are free here. Nothing changed greatly, though.

And then there was the Somerset case a few years back. A man who was a slave in England ran away and was to be sold to the Indies as punishment. When he was taken off the ship, the case was tried in the high court in England, and Justice Mansfield ruled that that man could not be held as a slave. When the news arrived here, well, it arrived very differently than what it seemed to be. People thought that slavery was ended completely in England. It was not, but it was a crack in the wall that was significant. Somerset got us freedom. I heard, well it was in the Virginia Gazette, that there was a ball held with 200 Negroes and their ladies in attendance, and Justice Mansfield himself was a guest. I can scarcely imagine such a thing happening here in Virginia.

Lloyd: You said before you were born... when were you born?

Eve: Oh, I was born '42. Not of this city, at Barkley. Do you know it? Right up the river. I came into the Randolph household when I was about 8 or 9. They had suffered a smallpox epidemic and lost a large number of slaves in their household, so I came to take the place of the woman that waited upon Mrs. Randolph.

Lloyd: So, you have always been an inside, a household, slave as opposed to a field slave, is that correct?

Eve: Oh no, when I was small, there was much work to be done. If you were a child, you could be spared easier than the adults that are skilled. You get my meaning&ndash some of the worming, some of the weeding, so the adults could do some of the more labor-intensive tasks. So I'm much used to it. I've never worked the fields as an adult, though.

Lloyd: You were, at one time, valued by the Peyton Randolph household as worth at least £100, making you one of the more valuable slaves in with Peyton Randolph. This sounds an odd question, but it's not, really: were you happy to be worth that much?

Eve: It was embarrassing. The ordeal was awful. After Mr. Randolph died in Philadelphia, it was a few months after, men came through the house and assigned a value to every thing, every thing in the home, save for a few personal items. Then they turned to us. It was as if you were standing there unclothed -- we were not -- but we were being looked over, asked about our skills, asked about what we did, asked about our age. It was an embarrassing ordeal, and I was glad when it was over.

Lloyd: Still, you came through it rather well.

Eve: It just reminds you how some people view you, when you hear a value assigned to you. Well, I think about it this way: There's a woman there on the property named Succordia, she is an elder. I do not know for sure, but I would say she's maybe upwards of 60. And when the assessor said that she was only worth £10, well, she cannot work as she used to, but she is invaluable to all the children there.

My work keeps me away from my son, even though he is right on the property with me. We scarcely sometimes only have a few moments to spend with each other. But I know that when he is with Succordia, he is learning how to be a proper young man. He is learning about how to be someone who has principles, and someone who has values and morals. To me, that makes her one of the most valuable people there. The same with Braches, one of the eldest to the property, and though he is ill now, they are my son's grandparents, since he has not ever met his own.

Lloyd: You say that she may be, you're not quite sure, upwards of 60. She was assigned a value of only £10, because she's not as good at working as once she was, as none of us are as we get on. Now, when you are upwards of 60, will they value you at £10?

Eve: It is quite possible. I've never been affected with bad health, which is a blessing. I have never been injured, never had any bones broken that have needed to be set. I am past my childbearing years, I do believe, so there is no fear that childbirth, or the complications that come with it, will affect me. So, I do not know what may happen.

Lloyd: Has it ever occurred to you that you would like to be free by the time you are 60?

Eve: Well you think about it all the time. That is the most ironic thing about all these goings-on. Them that know the most about freedom are the ones that are denied it in the first place. But the ideas of freedom are, well, not to live as the Randolphs. Not to live in a sizeable home and to have properties in other counties and to have other people serve me, but to make a living on my own, to be able to provide for my son, George, to know that I can leave him a legacy, maybe a bit of land, money and a home. To make choices about what will happen to him, make choices about what I do, and to know the work that I am doing is going to me and my son, instead of to someone else.

Lloyd: So, all the talk about revolution really doesn't have that much meaning for you at this moment.

Eve: Well, I will say to you that the words that the gentlemen are using are the same words that Negroes can use. There are more vocal demonstrations of that, further north. From 17 and 73, Negroes in Massachusetts Colony have been drafting petitions. Some of them are Negroes that are slaves, saying they wish to be free, saying they wish for their own bit of land, and to settle their families under a fig tree. Some of them are Negroes that are already free, but still are bound by laws that rights are not, much the same as free Negroes here in Virginia. Well, there is that clamor amongst the Negroes here. There has been no petition that I know of to come from this colony, but the attitudes are the same.

Lloyd: So when the, for lack of a better word, revolutionists, patriots, I really don't care, when they speak of freedom, they are not speaking of your freedom. They are speaking of a different freedom. Does that trouble you sometimes?

Eve: Well, it seems, some may say, ironic. Some may say it is hypocrisy. It is as if they cannot see the nose on their own faces. There are some of the gentlemen even that agree. Dr. Rush, from Philadelphia, did say that liberty is so tender of a nature that it cannot thrive long in the neighborhood of slavery. So I don't know if the gentlemen know what they are doing, and do it anyway, or if they are completely blind to what it is they are doing. I don't know which one is worse.

Lloyd: Do you think it's at least possible that for the revolutionists, they simply don't consider dark-skinned people worthy of freedom?

Eve: That is a possibility. It does not seem to be in line with many of them that claim to be Christians, but I'm sure that is what some of their beliefs are. There are some, a few years ago, that wished to stop the trade of Africans coming into the colony, and much of that has tapered off, as it were. But to stop the business of slavery entirely, only a few, far between, even have that view.

Lloyd: Stopping the trade might, in fact, be protecting your investment. If you had more slaves brought in, the price might fall.

Eve: Well, many of the Negroes to this colony are them that are born here. One of the first laws passed dealing with slavery states that the status of the child is that of the mother. So, that is a burden every woman who is a slave must bear. You are overjoyed to be a mother, but you know that every child you have will become the property of your owner.

With that law being passed well over 100 years ago, I would say that I do not know for sure, but I would say that near all of the slaves about the city, save for a few, were them that were born here. Their parents were born here, their grandparents, and maybe even their great-grandparents were born here. There is still a trade, but it is not much the necessity it was when we were a younger colony.

Lloyd: Change tacks real quick. Is there anything to fear from independence, from your point of view?

Eve: Well, I see things going much the same way they have, saving for the gentlemen, who make the laws who've traded one tyrant an ocean away to be the tyrants themselves, here. There's already been Committees of Safety, where there has been arm-twisting to get people to see their ways. If you did not agree with them, they may publish your name to the paper, tell people not to patronize your business, leave tar and feathers in front of the door of your home; does that sound like people that want true liberty, or does that sound like people who wish to take the turn being the tyrant themselves.

Lloyd: That’s Colonial Williamsburg: Past & Present this time. Check history.org often, we’ll post more for you to download and hear.