London’s foundling children were orphans in the midst of a crowded city. The exhibit Threads of Feeling tells their stories, as well as those of their mothers.

Podcast (audio): Download (12.6MB)

Subscribe: RSS

Transcript

Harmony Hunter: Hi, welcome to the podcast. I’m Harmony Hunter. We have a really fascinating show for you this week centering around an upcoming exhibit at the museums of Colonial Williamsburg. The exhibit, Threads of Feeling, opens May 25, 2013 and runs through May 27, 2014. Threads of Feeling centers around the story of the London Foundling Hospital. Our guest today is John Styles, curator of the exhibit on loan to us from the London Foundling Hospital Museum. John, thank you for being here today.

John Styles: It’s a pleasure.

Harmony: So, John, tell us first what is the London Foundling Hospital? What did they do there?

John: It's called a hospital, but we think of it as more of an orphanage. It was set up, founded in 1739 in the middle decades of the 18th century to take in children, in fact babies, very, very small children, who had been abandoned in the streets of London. London was then, as now, the capital of England and was a growing, very successful center, but was characterized by real extremes of wealth and poverty. There were the lords and ladies and the bankers and merchants at the top of the pile but there were very, very poor people at the bottom. People felt, richer people felt, philanthropic people felt, that there was a real problem of child abandonment and that something had to be done about this for the good of the children.

Harmony: We’ve talked about these children as being abandoned, but often they were also surrendered by their mothers. How did that process work when the children were brought to the Foundling Hospital?

John: Well yes, behind the setting up of the hospital was this idea that there were children being just left in the streets of London with no one to look after them. And of course, that did happen from time to time then as it still happens today. But actually most of the children who came were, as you say, brought by their mothers who felt that they just couldn’t look after these babies anymore. I mean we’re talking about one week or two-week-old babies. Its often thought that these were all the offspring of single mothers, that they were illegitimate children, but that’s not strictly true. Something like a third of them were probably born to married parents who had also fallen on hard times. So most of the children who came were children who had one or more parents, but whose parents were just so poor, so impoverished they just couldn’t look after them.

Now at the start, the funds available were limited because this was a subscription; it depended on the generosity of benefactors. And so they had to restrict the numbers and something like three quarters of the mothers who came didn’t have their children admitted. The way they organized that was, to our eyes, rather harsh, although they were trying to be fair. They actually instituted a lottery. The mothers would come into the hall these days, several days a year when they did this, and they’d put their hands into a bag which contained different balls and if they pulled out a white ball that child was in and if they pulled out a black ball they were rejected.

And hence in English we sometimes say someone is being black balled and this is where that phrase comes from. So it was quite tough. You took your chances and only about a quarter got in and there must have been hundreds and hundreds of disappointed desperately upset and disappointed mothers whose children didn’t have the chance to get to the hospital.

Harmony: Heartbreaking as it is to consider these women having to make the choice to surrender their children, what do you think, what can we surmise was behind their choice to try to get them admitted to the Foundling Hospital? Did they believe that the children would receive better care? Would be better provided for? Would maybe receive some kind of an education? Why would they make that choice?

John: Well I think of in all these desperate situations there’s two things at work. On the one hand there’s a sense that they just can’t go on. They just can’t cope and I think you do get letters left by the mothers or dictated by the mothers because many of them were illiterate, that make it clear that they were in absolute, in many cases, in absolute desperation. But on the other hand the Foundling Hospital seemed a very attractive option when you were in this kind of predicament because it was well funded. By 1741 it had this enormous new building, magnificent building, which was built on the then-outskirts of London. It guaranteed that the children would be given medical care, would be carefully looked after and then would be sent to school and eventually given an apprenticeship which was the general way of getting into work in the 18th century. So as institutions of this sort went at the time, it was doing a pretty good job and you see a number of mothers leave letters which pretty much say, “I can’t really look after this child properly anymore and I’m giving it over to the Foundling Hospital because I hope that way it will have a better future than I could provide it with.”

Harmony: And what do we know about the conditions and the survival rate inside the hospital for the children?

John: Well they’re, to our eyes, they’re not good at all. Something like two thirds of the children died, but we should remember that something like two thirds of children of poor people in London died at the time. So the death rates in cities — and this was not just true in England but across the great cities of western Europe and in cities like in towns and cities like Philadelphia and Boston in colonial America — death rates were appalling. I mean cities were death traps.

The healthy places were out in the country away from infectious disease. All these people crammed together in cities fostered tuberculosis, dysentery, all the other diseases that we’ve gradually overcome in the course of the last century, but at that time were the great killers. So the death rates were very high and of course what you were getting was children who were already often weakened by poverty and cold and being out on the streets and so on.

But if the babies got through to a year or two years old then their survival chances were actually pretty good. So I think on balance one can say the hospital didn’t do worse than the generality of people in London at the time. Once the babies had become little children of two or three then the hospital actually did a pretty good job and gave them good opportunities.

Harmony: The really remarkable thing about this exhibit is that it tells us so much. It gives you such an eye-opening insight into the life of the 18th century poor women and their children. But where you get involved in your area of expertise is actually textiles. There’s a whole second side to this story. Tell us how textiles are part of the story of these little London orphans and what they show us that we really never knew before.

John: It does seem odd to our eyes to think that textiles is a way into this story; the story of abandoned babies. But actually they’re crucial and they’re crucial because the hospital had a policy that the mother should be entitled to reclaim her baby if her circumstances changed. And this wasn’t just true in London, there were orphanages and foundling institutions in many other parts of Europe and they almost all have the same rule. And I think its testimony to the very deep gut feeling in western culture that babies should be with their mothers. It’s just a kind of baseline assumption at the time, as it remains in many ways, that babies ideally should be with their mothers.

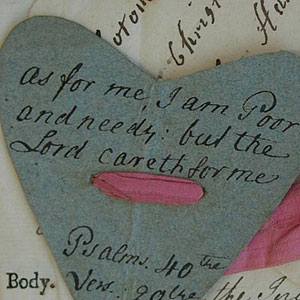

Of course, the Foundling Hospital was built on the assumption that there were circumstances in which the babies couldn’t be with their mothers, but the mother had the right to reclaim the baby. Now the problem was that if these babies were left when they were a week old, two weeks old, and the mother came to reclaim them when they were two or three years old, how does she know that the baby she’s reclaiming is her baby? Because babies change so much in the first months and years of life. It might often be very difficult to tell. So the hospital needed some way of linking this baby and this mother. One of the key ways they did that was to ask the mothers to leave a token.

In fact, they had over the gates of the hospital a sign saying, “Bring a Token.” And the token, more often than not, was a piece of textile. Why that? Because what did these impoverished poor women have? What they had was mainly the clothes they stood up in, and the clothes they dressed their babies in. In addition to that, textiles were a colorful and often distinctive. So what tended to happen was that the mothers would leave a scrap of textile often cut from the baby’s garments with the hospital clerks and the hospital clerks would compile an entry, a registration form for each baby, and then pin or clip the textile to it. Â

And you can tell that’s what’s going on because the textiles tend to be fairly colorful and decorated. The majority of textiles in the 18th century world were probably rather plain and everyday, but the mothers and the clerks picked out decorated, distinctive textiles so that the link could be made between mother and baby and often clearly the mother kept the textile, the piece of textile that had been cut in half, so that half stayed with the hospital and the baby and the other half was kept by the mother. And there are letters in the hospital’s archives saying, you know, “I left my baby eight years ago and I left with my baby, I left a piece of textile that was like this,” so the mother actually knew what the textile looked like.

Harmony: And you point out in your book Threads of Feeling, which is the companion to the exhibit, that this class of textile is so rarely preserved; what gets saved in museum collections, what gets handed down through generations are usually really the very finest garments, the richest garments, the most elaborate garments, but we have so few surviving examples of workaday fabrics of the working class. Did this just really open your eyes to what those people were wearing?

John: Absolutely, because I came into this because I wrote a book called The Dress of the People which was about what ordinary people in 18th century England wore and it was very, very hard to find any surviving garments. I mean, as you say, museum policies then and now collect what as they see as the best, the most fashionable, the top of the market. So I just couldn’t find any museum which had ordinary people’s clothes.

Now we know that most baby clothes in the 18th century for poorer people were actually made from the cast offs of their parents, because when a gown or a petticoat had worn out, there would still be sections of it where the fabric was absolutely fine and unworn and that would be cut out and made into various baby clothes. So in a sense, these items that were left with the babies, sometimes cut from the babies' clothes, sometimes given by the mother were, it seemed to me, a very good guide to the sort of fabrics that the mothers had worn as adults. It was probably a very close relationship between what was left with the babies and what poorer adults wore, especially poorer adult women. It’s interesting that it tends to be women’s fabrics that survived with the babies in the Foundling Hospital collection, not men’s fabrics. I suppose that makes sense because it’s all really about the bond between the child and its mother.

Harmony: What has been the impact of this insight of being able to see these fabrics, touch these fabrics and study them?

John: Well I think for me one of the most important things has been to completely change the way I think about the famous Industrial Revolution of the 18th century. The end of the 18th century is the moment when in Britain, and very shortly after in America, the making of textiles moves from being done at home by hand into factories. The first big factories are really textile factories; cotton mills, worsted mills. And its really changed my view of that, because one of the things one sees in the foundling textiles are masses and masses of cotton fabrics. And yet these all date from the 1740s and 1750s: the years before the great inventions that created the industrial revolution, and some say therefore create modern society.

It’s that the new inventions didn’t create the market for the new textiles. It was the fact that the new textiles were already so popular, even when they were made by hand, that stimulated manufacturers to go out and invent new and cheaper ways of making them. So it kind of turns a lot of the ways we think about the industrial revolution on its head. We stop thinking about it as, if you like, being led by the great inventors and actually we find it’s led by fashion and by fashion among pretty ordinary women as it turn out.

Harmony: When we think about these twin stories of the orphan surrendered by lower class families and then we look at the fabrics and textiles that tell us so much about the daily life of these women and the work that they did. How do those two studies help us have a better understanding of how society has changed or maybe how we have evolved and are maybe doing the same thing in a little bit different way today?

John: I think my view of this is gone in two ways. First of all I’m struck by how these objects tell us something about the way we as a society deal with things and especially textiles. I mean these mothers put great thought often into the textiles they left as tokens. You’ll find they’ve cut out from printed cottons and linens little butterflies and birds and particular animals and flowers, all of which somehow I think express their love for the children they’re having to leave with the hospital. And I don’t think we’re so, as a society, so attuned to expressing emotion through little things, little pieces of fabric. It’s as if in the 18th century there was a whole vocabulary of things, a material vocabulary, if you like, which expressed love and affection. I think that still goes on and but it goes on in a slightly different way now.

When mothers and children are separated now there’s great emphasis on making sure that the child has some object which can remind it of the mother. So in the case of orphans, in the case of international orphans where the mother is in one country and the child is a refugee in another, you’ll get a lot of stress by social workers and so on in trying to get objects from the mother that can go that the child can have as to remind the child of its family and its mother in particular.

The sad thing about the foundling textiles is that the foundling children virtually never got to see the textiles. It’s the ultimate irony and sadness. Here are we in the 21st century able to see these thousands and thousands of textiles which were meant to connect mother and child, but those children never saw them. They stayed in the record books of the Foundling Hospital there in case the mothers came back to claim their child. But sadly, very few of those mothers did ever claim their children and so the children never really got to see the textiles.

Harmony: What a remarkably rich and touching story. We want to make sure that everybody gets a chance to come out and see this exhibit on loan to us from the London Foundling Hospital Museum. We’ll have it at Colonial Williamsburg opening May 25, 2013 and running through May 27, 2014. In the meantime, you’ve got a remarkable on-line exhibit where we can actually see some of these samples that we’ve been talking about at www.threadsoffeeling.com and that’s where they can see some samples of some of these little scraps we’ve been talking about.

John: They certainly can.

Harmony: John, thank you so much for being our guest today. It’s been a fascinating conversation and I hope all of our listeners get a chance to come out and see some of these remarkable objects and learn more about this story.

John: Thank you Harmony. It’s been a real pleasure.