You can call him a shoemaker, you can call him a cordwainer; you can even call him Al. But one thing you must never call him is a cobbler.

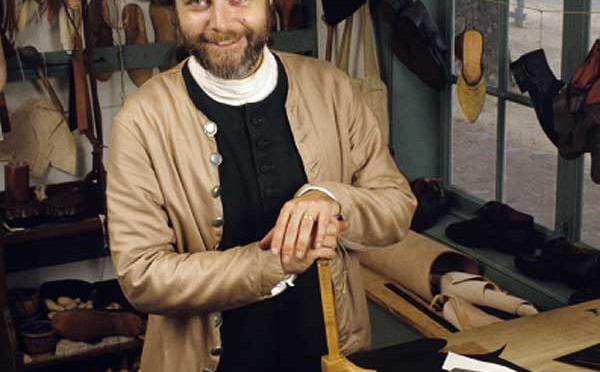

Master boot and shoemaker Al Saguto discusses his trade in this week’s show.

Podcast (audio): Download (7.0MB)

Subscribe: RSS

Transcript

Harmony Hunter: Hi, welcome to the podcast. I'm Harmony Hunter. Continuing our series on historic trades, this week we're talking with the master of a trade we could hardly do without: the shoemaker. Our guest today is Al Saguto, who's master boot and shoe maker in Colonial Williamsburg's Historic Area. Al, thank you for being here today.

Al Saguto: Well thank you Harmony.

Harmony: We've been talking to a lot of the tradespeople of Colonial Williamsburg's Historic Area, but I understand that shoemaking, as a trade in the 18th century, was one of the most widely-practiced trades. Why was there such a demand for this trade?

Al: Well, first of all, everybody's got feet and they all have to have shoes. The rate of consumption per pair, per year, per person from the 18th century doubles from about two pair a year to about four pair a year, so it necessitated a lot more shoe makers.

Harmony: We know that one of the first trades that arrived in Virginia is the shoemaker's trade. Jamestown colony is established in 1607. Sixteen-ten we see the first shoemaker. Does that suggest something about the necessity of this as a trade? If you're breaking a wilderness, you're going to need shoes.

Al: Well absolutely, and Britain had had some experience in supplying its colonists from a distance just as the Romans did centuries before them. The supply lines were very long, however, and the idea that the London Company had at the beginning at Jamestown was to sell them everything they needed and that wasn't very practical when it came to shoes at the rate that they were wearing out. So they went on a very aggressive recruiting campaign in London to recruit shoemakers and other trades too by 1610 to come over here and supply the needs.

Harmony: I've also heard the shoemaker called the cordwainer. What is that about?

Al: Well, that's an old French term that we couldn't get our tongues around. The French word is "cordonnier," which means a worker in cordovan leather in French. The English just sort of chopped it into cordwainer.

Harmony: And now in the parlance of our times it's shoemaker.

Al: It's shoemaker, or it's still cordwainer in the inner circles.

Harmony: But the one thing that you will not tolerate being called is a cobbler. How is that different from what you do?

Al: Well, according to the dictionaries of the time, a cobbler is a bungling workman in general, especially a botcher or a mender of old shoes. Shoemakers and cobblers have lived in enmity since the middle ages because the cobblers wanted to fix old shoes and sell second hand shoes and of course the shoemakers, or cordwainers, wanted to make and sell new ones.

So we basically squashed the cobblers through legislation. They wind up being sort of the wretched trade that sits out in the street with the dogs mending old shoes. They're prohibited from buying new leather. They have no friends.

Harmony: Tell me about how you make a shoe. What are the materials that you need? What is the assembly process?

Al: Well it varies widely between men's shoes and women's shoes at our time period. Most of the women's shoes are made from textiles in the uppers, the upper part of the shoe is made out of silks and wools, the heels are carved out of wood. The soles, of course, are leather and it's all stitched together around a wood form called a last.

The men's shoes are all leather; top, bottom, inside and out and they're likewise made around a wood form. The whole process was divided into specialized tasks within a shop very early actually, about 2,000 years ago. So it's not one person making the shoes start to finish.

You have the master of the shop, who does the pattern work and who buys the leather. So he cuts it out to make sure none of it gets embezzled. Then it goes to another worker called a closer who sews the uppers, the real thin parts of the shoe together. Once the uppers are completed, the master cuts out the rest of the bits and gives them to the journeymen in the shop and they build the shoe around the wooden last, again sewing and stitching all the way.

Harmony: I imagine you must have some specialized tools to accomplish all of that. What are some of the tools that are distinct to the shoemaker's trade?

Al: Well, relative to other trades like the blacksmiths, we use very few tools compared to some of the other trades: mostly awls for sewing, curved pointy things for poking the holes for the sewing, knives for cutting, pinchers for pulling and stretching the leather, polishing sticks and rubbing bones to polish the work up when you're done and that sort of thing. The old phrase was, "A good shoemaker could make a pair of shoes with a knife and a fork." But all the while, the tool makers and marketers of tools were trying to make more and more tools to sell to more and more workmen.

Harmony: And in the 18th century we don't have a distinct form for the left and the right foot?

Al: Not any more. The crooked-shaped, crooked forms were given up about 1600 for economy. So like your socks or your stockings, there's no shape to it until you put your foot in it.

Harmony: I want to think about some of the styles that were popular in the 18th century. What are people looking for in a shoe? What's defining the style of the time?

Al: Well shoemaking, like a lot of the other trades, were real arbiters of fashion through all the centuries. The number of styles for men and the number of styles for woman were very diverse. You had slippers for indoors, common shoes for wearing every day, strong shoes for workers and say rural workers and farmers, boots for riding, other types of boots for hunting on foot, even specialized forms like tennis shoes were popular with the French who were quite given to playing the royal tennis in specialized shoes, dancing pumps for dancing.

Good heavens, there's endless variety of styles. Actually there was an archeological example dug up on the eastern shore of Virginia from about 1660 and the toe of the shoe forked, not real pronounced in the devil horns like some of them did in Europe, but into the little forked shapes so even the outrageous styles were making their way to transatlantic.

Harmony: You mentioned evidence that came from an archeological dig. I imagine that must be one of the sources of research that you use. How do you know what you know about shoes and shoe making in the 17th and 18th century?

Al: Well, you've really hit the nail on the head. Archeology probably informs about 95 percent of what we do and know about shoes in the time period; how they're put together. Fortunately, most of them have fallen apart over the years so we can actually peek inside of them, which the curators don't like us to do with nice shoes in Collections. So they're very informative in that regard. Shoemaking also has benefited from having a number of sort of do-it-yourself textbooks since the 17th century published on how to make a shoe. That also informs our work.

Harmony: So we have the shoemaker as a resident trade in the colony, but he's also competing with imports. How is that organization working?

Al: Well, the vision for the colonies in the beginning was one of creating a new market abroad for goods from home. However, that model didn't succeed terribly well and you had entrepreneurial people here too that wanted to make some money. So early on, the shoemakers in Virginia were making shoes, but they were exporting them out of Virginia. Local people were not getting the benefit of them. They were going off on the coastwise trade, down to other colonies and areas.

So by 1661 Virginia nationalized the tanning and shoe making industry in the colony. It was that important. They basically stipulated that each of the 16 counties at that time had to erect one or more tan houses and shoe manufactories and they forbade export. So while this is going on locally, the shoemakers in London of course see this as a cash cow. They're exporting up to 40,000 pair a year they send here in the 1640s. So you've got locally-made products, some of which are being sold locally, some are being exported, and then you've got thousands and thousands of pairs coming in from England as well.

Harmony: Is there a difference in quality between the imported or the way that the shoemaker in colonial Virginia constructs a shoe versus the way that the imported shoe is going to be made?

Al: Not fundamentally. The shoemakers here are English shoemakers, or at least one generation removed, or they were trained by English shoemakers. The product, if it's substandard, isn't going to sell. At least it's not going to sell locally where there's sophisticated taste. You might get away with it on the Eastern Shore, down in the Carolinas. But locally the product is pretty comparable to shoes coming out of London. The point there is, no country ever exports its best stuff. Even though there are a lot of comments made during the 18th century about how superior British goods are and how wonderful they are, and in many cases they were, the best never left Britain.

Harmony: What's your favorite thing about practicing the trade here in Colonial Williamsburg's Historic Area?

Al: I think one of the most delightful things for me as a shoemaker for almost 40 years now is when people put on a shoe or boot that I made and they go, "This doesn't feel like a new shoe, this feels like my foot." I feel like I bridged that gap between something that I made with my hands throughout the day that somebody else has put on and interacted with it successfully, that it works as a tool, as a garment. I mean you figure making trousers, you know, you could miss and make them an inch too short and they just sort of look nerdy, but a pair of shoes you don't have that luxury if you miss, you know, you cripple somebody.

Harmony: We can see your work throughout the Historic Area on historic interpreters and even interpreters like George Washington and Thomas Jefferson. Where can people come see you at work?

Al: Well, the shoemaker's shop is located right next door to the Greenhow Store on the Duke of Gloucester Street in the middle of the Historic Area. We are the smallest interpretive space in the entire Historic Area, but we're in there diligently making shoes, trying to give people a good understanding as we like to say.

Harmony: Al, thank you so much for being our guest today. We hope that everybody makes it by your shop on their next visit to the Historic Area.

Al: Why thank you Harmony.