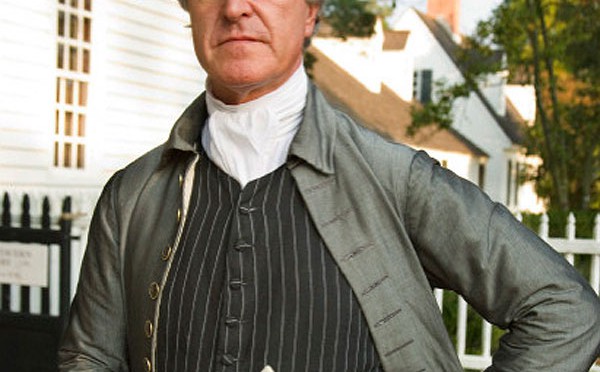

Political pressure and personal bias have hounded American journalists since the first newspapers were printed. Interpreter Dennis Watson talks about the Virginia Gazette.

Podcast (audio): Download (2.7MB)

Subscribe: RSS

Transcript

Lloyd Dobyns: Hi. Welcome to Colonial Williamsburg: Past & Present on history.org. This is “Behind the Scenes” where you meet the people who work here. That’s my job. I’m Lloyd Dobyns and mostly I ask questions. The roots of American journalism took hold in the rich soil of the New World. Here to discuss the history of Williamsburg's own newspaper, The Gazette, is Dennis Watson, an actor interpreter who portrays newspaper publisher Alexander Purdie at Colonial Williamsburg.

I’m sure you’ve thought about it by now, what’s the difference between the colonial Virginia Gazette, and newspapers now?

Dennis Watson: I think when you look at the Virginia Gazette in the time that I’m portraying, I think people have a keener interest in what was going on around them. I think people want to know the detail and the particulars of whatever you’re printing, whether it be political, domestic, entertaining. I think the obvious difference today is, if you will, that today we have more than just newspapers.

Lloyd: Because of that, because newspapers were the only medium, do you think there was more influence when an article was printed than there is today?

Dennis: Well I think that when you look at the 1700s and the various newspapers that are printed in North America in the various colonies, what was the overall influence on the individual printer, who was putting out the newspaper weekly? The influence sometimes on the article is by the printer himself, or in some cases, herself. Or external forces – I mean, there’s examples of that. That’s a challenge today when people say, does the governor influence your newspaper? Does the House of Burgesses influence what you print? Many things influence what I print.

Lloyd: You said “the publisher himself or herself.” What role did women play in colonial publishing?

Dennis: Well, we know that we had a handful of women printers. I mean, the one that comes to mind is the one that I talk about on occasion: Clementina Rind. Clementina Rind is the wife of William Rind, who himself died in 1773. Clementina Rind, with the help of William Pinckney, decided to continue her husband’s Virginia Gazette. The difference is, there was a difference. Not only now do we have the first woman printing a newspaper in Virginia, but we have a woman who prints the paper in a different style than her husband did. You can look at William Rind’s Virgina Gazette, and you can look at Clementina Rind’s, and there is a distinct difference in how the paper is laid out, and the sentiment of the newspaper.

Lloyd: Which one was better?

Dennis: Well I always praise Clementina Rind. There’s a lot more poetry, she wrote a great number of articles, among the arrival of Lady Dunmore, for example.

Lloyd: Other than Clementina Rind, how did women fare in 17th, 18th- century journalism?

Dennis: Well, as I say, don’t forget we have Catherine Goddard, who prints with her brother, up in Maryland. We have Margaret Draper up in Massachusetts who is printing, and a few others. I think as Dennis Watson portraying Alexander Purdie, I work that into my interpretation on occasion. I work in the other printers in the other colonies, and the fact that there are other women who are laying out the paper, who are responsible for gathering the news and deciding what is going to go to the paper for men and women to read.

I like to bring in to context the fact that here in Williamsburg, and in Virginia as a whole for example, we have women who are involved in different businesses, who are paying taxes, who have responsibilities, who are influenced indeed by the actions of government. The same goes for journalism – what influences any woman printer, whether it be Clementina Rind or any other woman in any other colony in the laying out of her paper.

Lloyd: Do you know where, in the history of American newspapers, that your Virginia Gazette falls?

Dennis: Well, I at this time, am one of several Virginia Gazettes printed in Virginia. So I’m not the sole newspaper. As in many cases, in many colonies, there’s not one singular paper. By this time, there’s a number of papers. They’re all printing the news in one fashion or another. As the printer, and as indeed this being his roots if you will, having been here some eight and twenty years, he takes it upon himself to start to print his paper in a way which I feel shows a support for those in opposition, once and for all, to parliament’s intrusion into the rights and liberties of the people of America.

I think in great part, a great spark was the Boston events. In ’75 and ’76, Purdie changes the masthead of his paper three times. Which is interesting. If you look at the masthead of those newspapers, the later change is in ’75, and in ’76, he changes it twice. In the first half of ’76, the masthead reads, “Thirteen United Colonies; United We Stand, Divided We Fall.” He’s making a statement there as a printer, as a publisher. When he’s printing, indeed, the Declaration of Independence in July of that year, he’s changed it again to a coat of arms with a coiled snake. “Don’t Tread On Me.” The subtleties are there, and I think we know that Purdie himself, what he has is here, this is his foundation. He’s moving, if you will, with the sentiment of the times.

Lloyd: Purdie had his masthead to tell the people where the Virginia Gazette stood.

Dennis: Sure. And where he’s standing, himself. Prior to that, we know that a lot of printers – not all&ndashare printing in a way that shows both sides of the story. You might say that while Purdie is kind of taking that patriot cause, if you will. He’s taking the side of those who are opposing parliament and the war is underway and his newspaper is standing firmly behind it. I will print an opposing view. I will print the fears and worries of someone who is staunchly loyal to the crown and parliament still at that time. I have an obligation, I feel, as a printer, to put both sides of the story out.

Lloyd: So Alexander Purdie, in his own way, was more of a modern journalist than you would think, in that he tried to make both sides available.

Dennis: One could say that. The question is posed: do you write articles for the newspaper? People ask that question. Well I say, yes I have on occasion, and I’ve always made it known that I am the writer of said article. Or on something that I’ve reprinted from London or New York, I might give an opinion and put it to the paper showing that it’s my opinion or thought. I think you have to realize that at that time, articles we know again upon reflection looking back are being written by printers themselves and especially in the New England colonies in a fashion which are just totally fabricated propaganda. For the political cause if you will. But how much of that does the reader really know? I would say to a great extent, very little.

You might ask today, does the same stand today? Who writes the article, what’s the substance of it? I think today, people are very quick because of we have other media who are very quick to look into what a certain newspaper has printed and find out what’s the truth, what’s the basis of it, is it really accurate? For we know today in the 21st century here in America, we have, and people acknowledge politically the papers that are of one affiliation, or sympathetic to another. Just how accurate is the content? I think to some extent, it’s no different back in my time. But I like to say, no matter what it is, put it to the newspaper, let the people be informed, let them decide themselves.

Lloyd: Nowadays, unlike in your day, you can learn anything from anywhere in just a few seconds. In your day, it took at least 30 days just to get the news from London.

Dennis: Yes, ah, and even longer. I tell people, it’s always on the move. By the post from the North, by the post from the South, by ships coming down the coast up through the Indies, and by the ships who are crossing the Atlantic, coming up through the Mediterranean, up through the Indies. So I have, to use the modern vernacular, my own sources of information. I have indeed that which is constantly on the move and constantly coming to me. Do I then have an ability to have something perhaps that I can put to the paper quicker than one of my competitors? Yes, possibly. And so in that regard there is a delay. I’m not devoid of the news of what’s going on. It’s constantly on the move, it’s constantly coming.

I would say the only time indeed that it would slow us down is the wintertime, naturally, because transatlantic traffic, by ship, is less and more infrequent. But I’m not unable to fill the paper up from week to week. As a matter of fact, as I like to sometimes pull my paper out and show our guests, I’ll say, I have four pages of advertising, and two pages of news. But advertising is just as important indeed as any article of news I put to the paper. Because back then it’s different than it is today. Think about it. What is the ads put to the paper? Runaway negroes, slaves, indentured servants, horses lost, horses stolen, property for sale, and as we move into the ’75, here’s a fellow advertising his 41 pistols for sale, arms for sale.

It’s a wide and varied content of the newspaper, but very, very political as we move into ’75. Most of the paper doesn’t contain humorous articles any more. The space is filled with what’s going on in the congress, what’s going on with individual colonies, the political sentiment of the time. That’s the main focus. I mean truly, things have changed greatly. We’re in the throes of a revolution at that time. The different factions here in the colony of Virginia are looking for horses, they’re looking for mounted horses, we’re fighting a war. So things are distinctly different.

Lloyd: Would you prefer, do you think, being a publisher in colonial Williamsburg, or being a publisher in modern-day Williamsburg? Which would be more interesting to you?

Dennis: I think indeed I am quite content being Purdie in the 1700s, thank you very much. The competition is still there. The personal attacks still come, they do. I like to say, when I introduce myself on occasion, I’m Alex Purdie the printer and editor of the Virginia Gazette, liked by most but despised by a few.