Modern-day curators focus on reversible restoration techniques. Conservator Shelley Svoboda describes the renewal of the Carolina Room.

Podcast (audio): Download (2.7MB)

Subscribe: RSS

Transcript

Lloyd Dobyns: Hi. Welcome to Colonial Williamsburg: Past & Present on history.org. This is “Behind the Scenes” where you meet the people who work here. That’s my job. I’m Lloyd Dobyns and mostly I ask questions.

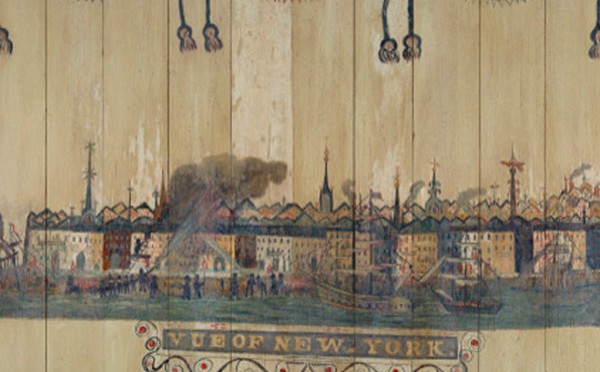

In 1836, a painter’s wall-to-wall decoration transformed a North Carolina planter’s parlor into an elegant sitting room. As decades passed, the painting dulled under layers of grime, soot, varnish, and overpaint. Painting conservator Shelley Svoboda is with us today to talk about the effort to reveal the original face of the Carolina Room.

Shelley Svoboda: The Carolina room was part of a planter’s house that was originally in south-central North Carolina, Wagram, to be exact, or Scotland County. It is still a rural community. The house no longer survives, with the exception of the parts that Colonial Williamsburg has in its collection.

Lloyd: Where can we see this, now?

Shelley: This room is currently on view in the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Collection that is in the new space adjoining the Wallace galleries. It is its own space, and it is installed as a conservation exhibition. It’s currently 65 percent clean. You can go in the room and see it 65 percent clean and the rest of it is still overpainted. So, it’s an opportunity to go in and really compare and contrast what it was before we have removed these unoriginal layers and to look at the beautiful paint surfaces that the artist, Isaac M. Scott, painted for us.

They’re from the American Fancy period. It was a time of celebration of the human creative spirit and imagination and putting things together that would never have been together. It has imitation wallpaper borders at the ceiling line, and imitation wood at the dados. The fireplace mantle is a faux stone creation, as are the baseboards. It’s quite whimsical, and it is visible as it was intended by the artist in its untouched state.

Lloyd: So it’s actually an example of the way things used to be done that was transformed to Williamsburg so it could be on display.

Shelley: That’s correct. The house itself is believed to have been a smaller, one-and-a half story home, so not a large ostentatious home, but one that was painted with these decorative interiors that were quite impressive, special, fancy. When the house fell into a state of decline in the early 20th century, these rooms were seen to still have merit, value and were removed from the houses and sold to antiques dealers, where they passed several times from dealer to dealer in piles of hundreds of pieces. Ultimately, in the ‘50s, it was acquired by the folk art collection here, Abby Aldrich’s collection.

Lloyd: Fitting those pieces together must have taken some considerable work.

Shelley: Well we know from the black and white photographs that were taken during the 1956 installation that they did struggle with it. I imagine it would have been very difficult, because the 137 or so-odd vertical boards are quite similar in their decorative schemes. They have different lengths, depending on whether they sat on a wainscoting, or a door, or a window.

But we know from the photographs that, one, they didn’t have all the parts initially from the dealer. They were missing a couple important dados, and had tried to put dados from a different paint scheme in. I believe also the mantle was not in the first delivered load. There is in the file a set of letters that is inquiring about perhaps getting some additional pieces from the dealer, would he check in his attics, etc., barns.

We did end up with all the dados for the room, and the correct mantle. We did retain these other dados, which give us some very interesting information about other parts of the house that don’t survive in their entirety. We also, we know that the ‘50s did a fabulous job getting this room together. Again, for something that was in hundreds of parts, it is a rare survivor in that it is virtually intact structurally.

They did get two boards in the wrong location. On the mantle wall, there are two small boards over the windows, that once the overpaint and grime was cleaned off, we could tell the swags did not match up. So we have put those back in their correct places. Now the room is as it was originally in the house.

Lloyd: How do you know what was original?

Shelley: We spent a fair amount of time, examining things closely with many different tools. Once the room was de-installed it was brought over to the conservation labs at the Bruton Heights Center. These, too can be toured by the visitor if they sign up to come in and see the labs, they can come see where we do some of this work.

But they are set up with very specialized equipment, microscopes that help us see the surface, microscopes that help us look at small samples, or cross sections that let us see the layer buildups kind of like an archaeological dig, where you see the earliest, original layers and you often see grime, or varnish that indicates either, grime would indicate a surface was exposed to the climate for a while, and having allowed soot and grime to deposit, and often varnishes are found as overpaint, as overpaint is often found on paint layers.

By looking with all of these tools and doing other types of tests, we are able to learn about what was original and what does not belong. Additional tests will help us determine a safe way to reverse the unoriginal things.

Lloyd: So, a great deal of your work is not with paint, it’s with scientific research.

Shelley: It is with scientific research on paint. So it’s all wrapped together. We know from our cross sections that this original scheme is very thinly painted. The overpaint was very thickly painted. Much of those are traditional oil paints, so we’re separating oil overpaint from oil original paint, which is why so much of the time resource for the conservation of the room has gone into the cleaning component.

A vertical board can take eight hours to remove the overpaint from the blue flat field section, but the fancy work at the ceiling line, the swag, can take anywhere from three days to three weeks to work on under the microscope to safely remove the thick daubs of overpaint from the very delicate, wonderful original high-key colors below.

Lloyd: You’re taking up to three days to work on an individual board. You must have the patience of a saint.

Shelley: Well, I also have a team of very dedicated folks that have been working alongside me for years.

Lloyd: Ok, they must have the patience of saints.

Shelley: They do, and we all do. I think that’s a component that you find in our building of specialists over here. We do have a keen interest in the integrity of the original, first of all, and then, a curiosity about the materials that go into both the original and historic restoration activities. We also have to have a knowledge of chemistry that helps us understand the new materials that we choose to consolidate the originals with.

They have to be different types of chemistry, so that in the future we can reverse it if we so decide to do that. The same with the varnish layer, it has to be a different chemistry. Unlike the ‘50s, where they chose oil paint to go on oil paint, we will in-paint to compensate some of the more major paint losses in the room, using a modern synthetic polymer that will have a chemistry very different from the original. So, down the road it will be a much less time-consuming process to treat.

Lloyd: This was done in 1836, according to what we’ve got. Was that a common decorating style, or scheme?

Shelley: Well, in some ways yes, and in some ways, no. It is common in that it is part of this American Fancy period, where many, many surfaces were enlivened with these creative human efforts of imitation wallpaper, imitation woods. It is rare in that this room is actually signed by the artist, Isaac M. Scott, and dated August 17, 1836. So we have a real time capsule of information that locks it together, and makes it even richer.

It is also rare in that it is surviving in its entirety. It is intact and represents exactly what it was originally. Many rooms of this period were stenciled, too. So it would be much more common to encounter a stenciled pattern. This room, however, is all free-applied artist’s paint. Even though there is repetition, say, in the swag areas, each one is unique in its width.

So he is not measuring anything, he’s free form painting these wonderful imitation wallpapers that themselves imitate hanging tassels and flowing flowers, and foliate elements. So it’s a wonderfully rich thing, and it’s a rare thing in that it has no surface kind of left unembellished. Again, it is signed and dated, so it’s a very rare example of this type of that was more common in the era.

Lloyd: And it’s now on display for people to see?

Shelley: It is on display, that’s correct. I think that people will be able to see the beautiful, beautiful high-key colors of the original artist’s hand. The blue is just so luminous. Even after working on it for years in the lab, walking in and seeing a wall installed in that lighting just brings it to life again.