Britain’s tax on paper goods was unremarkable in itself, but the colonies’ furious response surprised two continents. Historian Linda Rowe talks about the Stamp Act.

Podcast (audio): Download (3.4MB)

Subscribe: RSS

Transcript

Lloyd Dobyns: Hi, welcome to Colonial Williamsburg: Past & Present on history.org. This is "Behind the Scenes" where you meet the people who work here. That's my job. I'm Lloyd Dobyns, and mostly I ask questions.

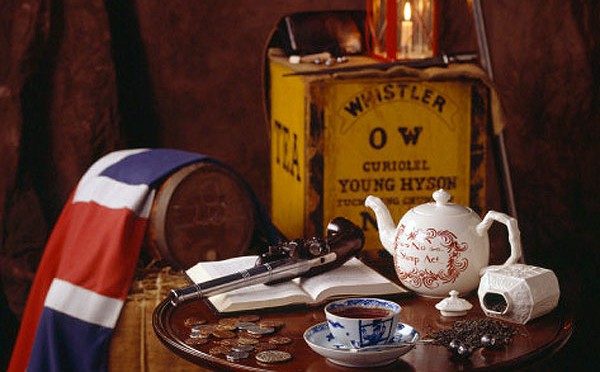

Throughout July, our program considers revolutionary documents, famous writings that helped transform ordinary discontent into all-out revolution. The Stamp Act is one such document. It said that colonists in America would have to pay taxes to England for things like newspapers, licenses, and diplomas.

Colonial Williamsburg historian Linda Rowe is here with me now to tell us what it was about these new taxes that infuriated the American colonists.

I guess, what is a stamp act?

Linda Rowe: Stamp duties had a long history in England. It was a way of collecting revenues by requiring that a stamp be placed on various products made of paper: paper itself, licenses, all kinds of court documents, wills, for example, even playing cards. So it was a way of raising revenue for the government to raise revenue in England.

So, as with many things – everything in life I suppose, and history – the Stamp Act that raised such a to-do in the American colonies is of course connected to other events. It grew out of the fact that the British government had just signed a peace treaty to end the Seven Years War, the French and Indian War, the American phase of that war was known in 1763. By that treaty, Britain acquired all of Canada, everything French east of the Mississippi, and some other areas. So their empire in North America that needed administering and defending was greatly increased. Not to mention, the accumulation of a large war debt for conducting seven years of war with France.

So, Parliament had the quite reasonable idea that the Americans ought to help pay for their own defense, and possibly to help reduce the debt from the war itself. So, George Greenville, in the British government, proposed in 1764, proposed to Parliament that they consider levying a stamp tax on the American colonies.

Now, this would have been the first direct tax on activities within the colonies. I think many colonists were adjusted to the idea that there would be maritime taxes, import duties, export duties – that kind of thing. But the Stamp Act, or the proposed stamp duty was the first time that a direct tax was going to be levied by Parliament on activities going on within the colonies. Everyday things where you needed paper to record your will, or play with a deck of cards, that kind of thing.

So, as soon as Greenville proposed a stamp duty to raise revenue in the American colonies, as soon as word reached America within a few months, an uproar began. The basis of that was that American colonists felt that their constitutional rights as British subjects were being trampled upon. A hallowed area of those rights was that you were not to be taxed by a body in which you did not have any representation. So this is really the beginning of that "no taxation without representation" that became such a familiar …

Lloyd: Rallying cry.

Linda: … rallying cry, right, a good way to put it. So when the Stamp Act, as it was officially known, was passed in 1765, in the spring of 1765, the colonists were already in an uproar about it and had sent petitions to be read before Parliament, memorials to be read in the House of Lords and to the king. Parliament refused to even acknowledge that any of those petitions had arrived in England. So, once the Stamp Act was passed, word reached America within a few months in the spring of 1765. Almost immediately, a number of activities started that …

Lloyd: A lot of people got angry.

Linda: … a lot of people got …

Lloyd: But the Stamp Act, the idea of if it's on paper you have to pay a tax. That was not particularly new in England, was it?

Linda: No, it wasn't. I can't give you chapter and verse for every time such a revenue had been laid in England, but it was a time-honored way of raising revenue. The individual amount that would be charged on any individual document was small. But you can imagine the proliferation of things that involves paper.

Lloyd: Yeah, if you take everything that's a piece of paper and put a stamp on it, you're going to get a lot of money.

Linda: Right. And one of the things that developed out of this is the fact that if the stamped paper hadn't arrived, or if the stamp commissioners – and I'll talk about them in a minute – had not arrived with their stamps, then ships might not be able to clear harbors because their paperwork and so forth had not been stamped. Courts might not be able to operate if they chose to wait for stamped paper or for the stamps to come. Newspapers, as you can imagine, particularly with pamphlets, newspapers themselves, almanacs.

Lloyd: Playing cards.

Linda: All kinds of things like that. Many newspapers ceased publication for a period of time. Some bordered their newspapers with black borders to say that they were going ahead …

Lloyd: A time-honored tradition.

Linda: … going ahead in spite of this. So, it was a mixed bag, but in every colony, quite an uproar began over this and continued. In Virginia, for example, the General Assembly meeting at the Capitol in Williamsburg was the first official body in the colonies to adopt a series of resolutions, now known as the Virginia Stamp Act Resolves, written and proposed by Patrick Henry and defended by him in debate with the famous "Caesar Brutus," or "If this be tyranny" speech, thereby establishing his reputation as a leading spokesperson for the patriot position.

Lloyd: For that reason alone, if I were the English Parliament, I would regret the Stamp Act. Because they made Patrick Henry a hero and Henry was a hothead.

Linda: I think you're right. And I also think that it's well to keep in mind the British position on this. They really were baffled by the American reaction, thinking that there was no question that Parliament had every right to tax Britons, wherever they lived in the world, whether at home or in the colonies. They had this large debt that had accumulated because of a war that was helping defend the American colonies, and has now enlarged the area that needed defending as a result of the treaty. So they were baffled by the American, what they saw as kind of splitting hairs over the right to tax the Americans.

I also think that there's something else here. There's the suspicion that there was a conspiracy to deprive Americans of their constitutional rights. When, in this period, when Americans are talking about recovering their rights or protecting their rights, they mean as British citizens. They don't mean as independent Americans. They're trying to protect or recover, as they see it, their constitutional rights as British citizens.

Lloyd: But it was their right not to be taxed unless they were represented, wasn't it, or have I got that wrong?

Linda: That is, that was certainly their position and there's ample evidence to support that. I also think that, you know, the other point they were making was then that their own legislatures in the colonies were the ones that had the right to tax them. That was where their elected representatives were – the House of Burgesses in Williamsburg. The Burgesses were elected by the electorate in the colonies, albeit more restricted than it is today.

Lloyd: Smaller electorate.

Linda: At the same time, each of the colonies felt that their own legislatures were where the right to tax lay, and it lay in the elected body, not with the Governor's Council and so forth. So that's another time-honored tradition of having revenue bills originate.

Lloyd: You know, if, from the English, the British point of view, you've just fought this war, and let's be honest about it – basically it is to protect the American colonies. No question about that, because it wasn't fought in Britain, it was fought here.

Linda: Right.

Lloyd: Basically the Ohio valley. So from the English point of view, asking you to help pay for your own defense is not an outrageous imposition.

Linda: Well, as all of us probably have feelings of patriotism that rise when we tell these stories, from this distance, I can easily understand that. That seems reasonable to me. So if you look at it from the English point of view, the British point of view, they were, I think they were, as I said before, baffled by this reaction.

I also wanted to point out that there were a few members in Parliament who actually felt that Parliament should not be taxing the Americans. You know, there were a few still small voices on the American supporting the American point of view in Parliament. But they were drowned out by the mainstream, of course.

Lloyd: The Stamp Act was never actually accepted in the American colonies.

Linda: It was not. That's a very good point. I mentioned before that I wanted to get back to the Stamp Act commissioners, or agents, as they were known. Each colony had an agent that had, would come to the various colonies with stamps and a stock of stamped paper, depending on which was needed. You know, from the very beginning, these agents endured harassment, being hanged in effigy, property destroyed, their lives threatened. One by one, starting in the Northeast in New England, these Stamp Act agents began to resign, throughout the spring and summer.

Lloyd: Gee, I wonder why.

Linda: Mob scenes ensued. One of the, I think it was the North Carolina agent escaped north from North Carolina, but he was identified by a crowd in New York and also forced to resign. Here in Williamsburg on October 30th, I might say that the Stamp Act was actually scheduled to go into effect on November 1, 1765. All of this knowledge that it had passed occurred back in the spring, so all of this lead up to the November 1st was quite an exciting period. George, Colonel George Mercer, the Virginia agent arrived in Williamsburg on October 30th. He was immediately assailed by a mob, an angry mob on the Duke of Gloucester Street. They kind of coursed up the street, surrounding him.

When they got in front of the coffeehouse, the governor and some of his council were sitting on the porch of the coffeehouse talking over the day's occurrences in the assembly. When Governor Farquier, a very popular governor, Lt. Governor Francis Farquier of Virginia realized what was going on, he strode off the porch, unconcerned for his own safety, and took Mercer by the arm and they proceeded up the street with the angry mob kind of muttering and …

Lloyd: Nipping at their heels.

Linda: … nipping at their heels. Eventually escorted him into the Governor's Palace, where things were allowed to die down. But he resigned the next day, of course.

Lloyd: What a wonderful greeting. Welcome to Williamsburg, we'll hang you.

Linda: Right. So those agents really didn't last long, and I think it soon became apparent to Parliament that repeal was the best course.