Forty-six pages from Thomas Paine’s pen whip discontent into outright rebellion. Public Sites Interpreter Alex Clark details the transformation.

Podcast (audio): Download (2.4MB)

Subscribe: RSS

Transcript

Lloyd Dobyns: Hi, welcome to Colonial Williamsburg: Past & Present on history.org. This is "Behind the Scenes" where you meet the people who work here. That's my job. I'm Lloyd Dobyns, and mostly I ask questions.

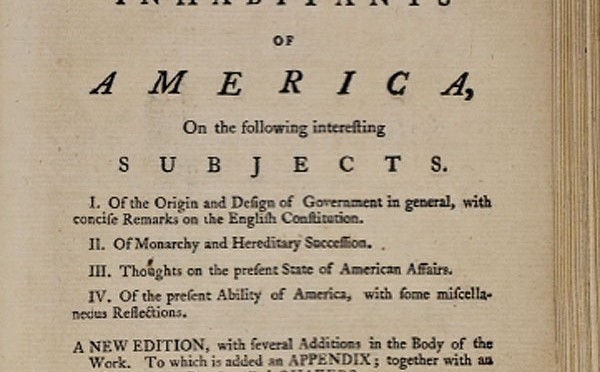

In our continuing series on Revolutionary documents, this week we'll take a look at Thomas Paine's pamphlet, "Common Sense. In it's pages, Paine transformed the raw emotions of colonial discontent into the rhetoric of revolution. Alex Clark, who is a public sites interpreter, is with me now to talk about the man who started a war, armed only with a pen.

In a specific sort of way, if you can – if someone walked up to you and said, "OK, tell me what 'Common Sense' did for the American Revolution?"

Alex Clark: It ignited it. Before "Common Sense," we were struggling to defend ourselves against ministerial forces that had been sent to dragoon us into an acceptance of unconstitutional taxes. Paine's pamphlet took it from an argument over taxation to the higher plane of struggle for existence, and a fight against a terrible power.

The point he makes is that he was all for reconciliation before the 19th of April of 1775. Once blood was spilled at Lexington and Concord, and later at Bunker Hill, he says, "We cannot pay a Bunker Hill price merely to change the British ministry and to repeal certain acts of Parliament. We must be set on the path for independence."

Lloyd: What did "Common Sense" say?

Alex: In broad terms, he takes on the traditional assumptions of members of the British Empire, particularly in America. He talks about the origins of government in general, and then relates it to development of the British form of government and shows how corrupt it has become. He takes on the origin of kings and derides the notion of hereditary kingship.

Then, he examines the affairs of America at the time, suggests that we have arrived at an intolerable situation, and makes the first really good plan of how the government should proceed, then finally talks about our capabilities in the military line. He's perhaps a little overestimating, but, nonetheless, we would succeed in the end.

Lloyd: Almost everybody on this side of the Atlantic overestimated how we would do militarily, except we did it in the end.

Alex: What they could see was the vast potential of the continent. That’s why Paine refers to our situation as "the cause of all mankind."

Lloyd: The pamphlet, "Common Sense," was what, 44 pages? Which is not what you would call very long.

Alex: No, but it was certainly enough to attack the traditional feelings of those who had taken pride in belonging to the British Empire, in such a way as to hold them up to ridicule, as well as an examination of common sense, which showed that it was in our common interest to separate. And then to lay out a coherent plan for that separation and the form of government that should ensue.

Lloyd: He read his audience correctly – which not many authors can do all that well – and he wrote for them.

Alex: He knew that he had to be amusing. A magazine editor publishes diverse pieces such as fables, political essays from England, original American essays. So, he knew that he had to be amusing and get just controversial enough not to antagonize either side in the political debate, but to boost readership.

Lloyd: Paine was the first man in America who wrote for the guys in the bar, so they could understand it. No Latin, no Greek, just English words that most people would recognize.

Alex: Not just English words, but the vernacular literature of the time. Throughout "Common Sense," he refers to the Bible, which is perhaps the most read book in the English-speaking world, and probably other places, too. He also refers to "Aesop's Fables," and just political maxims of the time.

For instance, in deriding the notion of hereditary government, he says that if hereditary government were such a good thing, then nature would not make a mockery of it by so often giving us an ass for a lion. Of course, he was referring to Aesop's fable of the ass in the lion's skin. He tries to impose on the other animals, dressed in a lion skin until his master recognizes his donkey ears and takes it off and beats him and says, "Notwithstanding you're dressed in a lion's skin, you're nothing but an ass."

It's really a political philosophy. He attacks the notion that we should remain loyal to an empire which has simply exploited us for its own gain, a king who is just a corrupt holdover of ancient bandits.

Lloyd: True, but not popular.

Alex: And that we should embrace our potential, a continent that could sink all future debts by the sale of the abundant land that we have. The thing that really strikes me about his pamphlet is, he's the first one that absolutely calls for a declaration of independence as a political necessity in order to obtain the notice of other European powers who might mediate an end to the war and also furnish us aid. Which, of course, Louis XVI's France does, without which we would never have won our independence.

Lloyd: The common man, that's who Paine was able to appeal to in a period when that was not what you would call a prime writer's audience.

Alex: Well certainly the tradesmen were not used to lavishing their money on political pamphlets. Paine had the knack for drawing everybody in and involving them, the common man, and advocating them as being a greater part of the government than had ever been suggested before.

He's the first to suggest a declaration of independence, assemblies in each of the states, submitting delegates from their various districts to a congress, and then writing a great charter for the United States through a continental conference to be drawn not only from the Congress and the people chosen by the state Legislatures, but the people at large. So they would combine knowledge and power, which he found the great motive to business.

Lloyd: Paine was a fairly – and I've forgotten how new – but a fairly new resident of what would be the United States. He'd, I don't want to say just come over from England, but theoretically, yes, he had just come over from England.

Alex: Yes he had. It was some time in early 1775. He works eight or so months on the Pennsylvania Magazine, and then begins writing "Common Sense," which is published in January. The striking irony is the fact that the same issue that published the advertisement for Paine's "Common Sense" was the one that carried the king's speech in the fall of 1775, in which he basically throws us out of the empire, says that we are beyond his protection, and we are at the mercy of the British army and navy.

Lloyd: I had never known that, that's quite remarkable. Is there anybody today who compares to Paine as a thinker and writer of revolutionary thoughts?

Alex: I would say that Walter Williams, he's a conservative writer, is able to do much of that. Also, the great political pundits -- the late Mr. William F. Buckley Jr. and, of course, Gore Vidal, his ancient antagonist.

Lloyd: Until he began to write, Thomas Paine was a bit of a failure. In school, he flunked out of what we would call high school, it probably is college now. Marriages failed, businesses failed. The only thing he seems to have been able to do successfully is think and write.

Alex: Well that's not perhaps exactly fair. He was withdrawn from his school because his father's staymaking trade was not going well. He was a master staymaker and a Quaker. His first wife died either of some lingering illness or in childbirth, we're not certain which. So he came home. He was not successful as a shopkeeper, but as I say, he had two stints in the excise and he became a spokesman for those officers. So that speaks of his ability.

Then, he undertook a very uncertain career as a writer at a time when there were very few who were able to make a living as a writer. So he was a success in that regard. Certainly he was an astounding success in enunciating the political philosophy of a new empire, which is what the Americans aimed at.

It would be later that Thomas Paine would actually take up arms in defense of this country's liberty. First, he was a political philosopher. He happened to hit upon a time and a subject that really formed the inchoate thoughts of the people and galvanized them into action.