Good as new isn’t always as good as old. Curator John Watson talks about conservation at Colonial Williamsburg.

Podcast (audio): Download (2.9MB)

Subscribe: RSS

Transcript

Lloyd Dobyns: Hi, welcome to Colonial Williamsburg: Past & Present on history.org. This is "Behind the Scenes" where you meet the people who work here. That's my job. I'm Lloyd Dobyns, and mostly I ask questions.

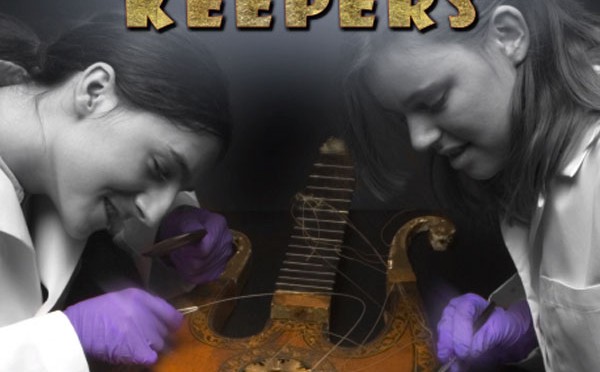

Restoring and conserving history is the business of conservators at the Museums of Colonial Williamsburg. This Thursday's Electronic Field Trip, "Treasure Keepers" explores the methods and philosophies that guide the practice.

John Watson: An object from the past is the product of hands, and of tools. It's very interesting the extent to which all of those tools and methods of construction are imprinted on the historical surfaces.

Lloyd: John Watson, conservator of instruments, is here to tell us more. The business of conservation has changed kind of dramatically in the last 25 years. You don't do what you used to do. Is that right?

John: That's absolutely true. Conservation has really developed from traditional restoration. It goes back, I think the Sphinx was first restored during the time of the pharaohs. So that long tradition of repairing what's important to us from the past goes back all the way.

What's changed in the last 50 years, dramatically, has been the way we approach restoration. Before, it was a matter of just replacing parts as needed to get things looking good again, refinishing old furniture, that sort of thing. Because we've come to see antiques as being documents from the past, full of evidence – physical, material evidence of the past – we've learned that traditional restoration tends to erase a lot of that evidence. So we approach restoration in a very different way. It's probably more appropriately called "restorative conservation" now.

Lloyd: You have a musical instrument, and it's wooden. Is your object to make it look like it did in 1775, or is it to make it, to learn from it of how things were made and put together in 1775?

John: Well that's a terrific example. As a museum, we look at antiques. We think of them as primary documents, as evidence of the past. So yeah, learning from it is the number one thing.

Now, to the extent that we can improve its appearance – if it has distracting scars and damage – so that the public, when they come and see it, don't really see the object, they see the scars. We might do something to reduce the appearance of the scars and make it look a little better. But those signs of age, very often, are the very characteristics where this record of the past is. So, erasing signs of age is not the business that we're in.

Lloyd: Ok, here we have an instrument. Which part of it do you try to fancy up so that it looks like it did in 1775, and which part of it do you want to leave as-is so people will see that yes it was used, and it was used like this?

John: That brings up an interesting aspect of all of this, and that is, we have to make judgments about the preservation worthiness of a thing. Sometimes it's perfectly fine to refinish and to replace parts – whatever is needed to make a thing function well or look good.

Other times, an object on the other extreme might be so historically significant and rare that to do anything at all would be to threaten some of that physical evidence. To give it the maximum kind of preservation, we might do nothing at all and leave it, in the case of a musical instrument, unplayable. So, there's that judgment that has to be made with every object that comes to us.

Lloyd: How do you make that?

John: Well, we look at a lot of things. We look at how rare the thing is. We consider how important the original maker was. If, here in Williamsburg for example, we know that the Bucktrout workshop advertised that it made spinets at one time. Well, no such spinet has ever turned up. If one ever did, it would be one of those things that we would never want to probably make any restorative changes to. We'd want to leave it untouched with all of its original evidence intact. That would be an example of that type of judgment.

Lloyd: OK now, we've got a pocket violin. Thomas Jefferson had one and played it. In that case, would you do more restoring, or conserving?

John: Well, there's rare and there's rare. A pocket violin, called in the period a "kit" in England and America because it fit in a pocket, was perhaps common in the period, but very few have survived.

So they're actually quite rare. We have, in our whole collection, we have just one. It actually was restored before it came into the collection, so it is playable. But here's a case where, although it's playable, it's very rare. It's the museum's job, one of the museum's jobs, to preserve things for the long term. If we're going to err on one side or other, as a museum, we may err on the side of preserving long-term. Therefore, the instrument is playable, but we allow it to be played very little.

Lloyd: Other than limiting its use, what are the preservation methods that you would use to keep this as-is?

John: One way that we preserve things is to just reduce the wear and tear from the environment. Changes of humidity, extremes of temperature, exposure to bugs that might eat the wood and cause damage of that sort, all of these environmental conditions cause things to age. We can control those conditions to some extent and greatly slow that aging process. Plus, as we've already talked about, the wear and tear of use. We can reduce that. We can be very careful in the way we store things, and the way we handle things.

Lloyd: If you're careful in how you store it and how you handle it, do people get to see it? If they don't see it, what's the sense of having it?

John: That's an interesting question. I've sometimes taken people into our large storage spaces in the museum. We have to turn on the light, and here's all these magnificent objects in the dark. One of the visitors sometimes says, "What a pity, all these wonderful things in the darkness, languishing in storage."

I've sometimes said, "Oh, no. This is like the Library of Congress reading room. This is full of historical documents that from time to time are visited by the world's great scholars studying them, and they reveal their secrets. They're in darkness because light, even light, causes fading and aging of objects."

When we do put things on exhibit, depending on the type of material -- especially paper objects, textiles -- those are shown for relatively short periods because the light does more damage to them. We will swap in, rotate the exhibits so that no one object gets too much exposure to light.

Lloyd: A violin, what does it tell you? You pick up this violin and it speaks to you in a way. What does it say?

John: That's a great question, and they truly do speak. We often have people coming to us with a violin that has a sticker on the inside that says "Stradivarius." They're all very excited, and they feel that they're going to be able to retire on what they'll get for selling this instrument. So, they bring it to us and it begins to speak, in a way.

We look at the workmanship, and we can gauge which century it was from by the kind of workmanship. After a certain time, you would expect the workmanship to be more machine-like, as if machines were used in the manufacture. You can look at wear marks. You can look at was it actually played, and for how long, by the wear. You can look at that sticker with Stradivarius' name, and was it the kind of printing that was actually done in Stradivarius' time? You can look at the types of damage that can only occur over long, long periods of time.

What very often happens is that what the instrument tells us is something like, "I'm about 50 years old, and I was made in a factory in Germany, and I'm a student-model violin." It may be worth a lot to you because of sentimental value, but it may not be what it pretends to be. It's the Stradivarius model, not a Stradivarius.

Lloyd: A heartbreaking discovery, I'm sure. Let's say that there really is an old violin. What would it tell you?

John: As long as the surfaces have been left alone and not scraped, tool marks are revealing of methods. Sometimes even on the inside of an object. There may be glue runs. Well, what does a glue run tell you? It tells you which way the object was sitting at the time that part was glued. What if you have one glue run running this way, and another glue run running crossways over it? Well that tells you a couple of things. It tells you that the object was sitting this way when that part was glued on, and it was sitting this way when that part was glued on. And, it tells you which part was glued on first is just one example.

But the closer you look, the more it reveals its entire process of construction: what tools were used, the methods and the order of construction. It's really quite amazing what the object reveals.