The little-known process of manumission was a means of securing freedom for a handful of Virginia slaves.

Podcast (audio): Download (3.1MB)

Subscribe: RSS

Transcript

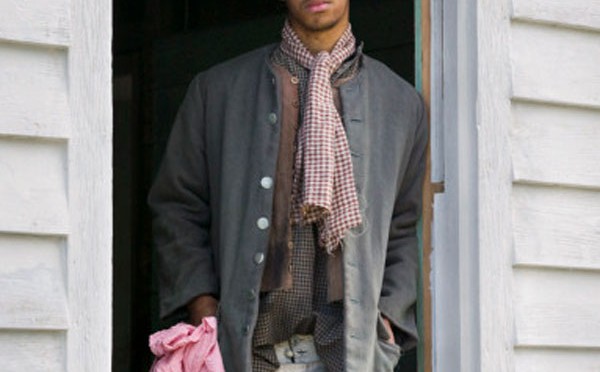

Lloyd Dobyns: Hi! Welcome to Colonial Williamsburg: Past & Present on history.org. This is “Behind the Scenes” where you meet the people who work here. That’s my job. I’m Lloyd Dobyns, and mostly I ask questions. This time, I'm asking Bridgette Houston, and in Colonial Williamsburg, she's an African American interpreter. We have been chatting about something I had never heard of. It was possible for slaves to be freed, or get their manumission, if their masters applied to the general assembly in Virginia.

Bridgette Houston: The process would have been to actually petition the governor's councilmen, and or the governor, to manumit your slaves. That had to be done through that petition up until 1782.

Lloyd: But why would a slave owner want to free a slave?

Bridgette: Some type of meritorious service may have been. There are two cases where one man, an enslaved man, had actually been able to come up with a cure for a particular disease, and one of the governors actually manumitted this enslaved individual. That was for a cure for a rattlesnake bite. The other one was for a particular venereal disease, and that slave was manumitted.

Lloyd: These are not your everyday slaves, when they are curing things like rattlesnake bites.

Bridgette: There actually were laws that did not allow slaves to legally administer medicine. My take on it is, laws are written, but are they always enforced? So if it's to one's advantage, as a European of that time, then I'm sure you would take advantage of that particular situation.

Lloyd: I had never heard of that.

Bridgette: Usually when you think of manumission, from what we learn from the movies and the history books, we usually think along the lines of, through a deed, buying your freedom, or last will and testaments. Again, that's not something that's readily available to slaves from 1723 to 1782, so it's after The Revolution, more into the 19th century that you find people manumitting them under the circumstances that we learn about from the movies.

Lloyd: I was aware that George Washington had declared that when his wife died, his slaves would be freed. She, very wisely, decided that right now was a good time.

Bridgette: That, too, is a little later. That's well after the Revolution.

Lloyd: Lafayette had a spy, who was, after the Revolution, not immediately, but when Lafayette came back, you could say he petitioned for James Armistead. Armistead was freed, and became James Armistead Lafayette. Was that part of this program?

Bridgette: No. Actually, by the time of the Revolution, when our last royal governor, Lord Dunmore, makes that offer of freedom to able bodies of rebelled masters to obtain their freedom, there are thousands who are going and actually joining the British in hopes of receiving their freedom. In Lafayette's case, that is a little different.

Lloyd: Because, in the first place, he never joined the British. He was a colonial spy, a Continental spy. OK, now, we have somebody who has done a meritorious deed, and his master or owner says, "That's a meritorious deed." How do you petition the governor? Just write the governor and say, "Hey, my guy did something really neat, can you manumit him, please?"

Bridgette: You know, you said something earlier: why would someone want to free their slaves? First, we've got to understand that it's an investment, and you really don't want to let all of your investments go. So, in the case where someone might petition for that particular slave, it's not going to be for many – it's one that you're looking at for that person, losing. Are people bothering to go through that process? Most people aren't, because of the legalities, so that's one of the reasons why you don't find a lot of people being manumitted.

Lloyd: I am guessing that it would have to be a complicated process that has a lot of roadblocks to getting it done. You have to ask the governor's council, they have to say yes, the council has to talk to whoever the governor's closest advisor is, he has to say yes.

Bridgette: Senior governor's council.

Lloyd: Now, the governor has to say yes. It's going to take a while.

Bridgette: Yes, it is. So, again, that's why it's not a process that you see happening a great deal. There's a free black man in Williamsburg in 1769 who actually – his name was Matthew Ashby – he actually had a sponsor, which was Mr. Blair, who was the senior governor's councilman at that time, to represent him. He was actually able to, because he owned his family as slaves, and he was actually able to petition for them to be granted to receive their freedom. It cost him £150 British Sterling, but he was able to come up with the money.

Lloyd: I have read of a free black on the Eastern shore who eventually was able to buy his family, but it was big money for those days. As I remember the story, he owned some land and sold part of it in return for his family. So, there are some stories like that, but not many.

Bridgette: No, I think another key thing, too, is that if you look at free blacks in general for that time – not people who are freed, but people who are free – most people who were free had likely never been slaves, they were born free. Because the status of the child, in Virginia, will be determined by the condition of the mother, as of 1662. So, we're talking about white women who were having mulatto children with African men, and that's just not something you hear a lot about. We usually think the reverse: white masters and enslaved women. But if you look at the government and how that law is written, it's really, in a sense, to control there being a large free black population even coming into existence.

Prior to, say, the 1660s, you don't have a large number of African women that are being brought in from the Caribbean Islands, it's more as they start to make their way into the western part of Africa that you see an influx of African women coming in. So, you had those indentured women and men coming from Europe who were working right alongside, as slavery is starting to develop, who are working right alongside those Africans.

What's happening, relationships are developing just naturally by association, assimilation, acculturation. Family structures come out of that, to the point that not only will they write a law in 1662 that says the status of the child is determined by that of the mother, but they will also write a law by 1691 that says the only – let me make sure I get this right – in how you are cohabitating, Negroes and Christians, it said, were not to cohabitate, and Negroes and Christians were not to marry. And, you know, why are laws written? Because something's happened. So we know that there were cases of …

Lloyd: (Interrupts.) If nothing has happened, then there's no need to write the law.

Bridgette: Right. Exactly. Same is true in today's society.

Lloyd: So you've got the law from 1662 that the mother determines the fate of the child. Then, in 1690 …

Bridgette: (Interrupts.) 1691.

Lloyd: Thirty years later, they say, yeah, but, except. And that would prevent the free black population from ever developing.

Bridgette: Right. And if you look at society and say, OK, slavery is solely based around the economy, what sense would it make to have a free black population that's going to be competition within a society that's dependent upon that slave labor?

Lloyd: I keep forgetting that, if you really want to know what happened in life, look at the economy. We know that not many people are going to do this under any circumstance, because: one; their investment goes "kaplooey," and two; the government doesn't want it done, anyway. Do you have any idea how many slaves did win some freedom through this process of petitioning?

Bridgette: As a whole, or are you talking about by the time of The Revolution?

Lloyd: By the time of The Revolution.

Bridgette: Well the numbers, we know, aren't really clear. We know there's a little over 4,000 who are actually going in hopes of receiving their freedom. What I don't think will ever really be clear to us, though, is what happens when the war comes to its end, and how many of them were actually able to obtain that freedom. Oftentimes, people had to leave. You had to be removed from, really, this country. People got sent to places like Canada, Nova Scotia specifically, Barbados, Jamaica, Freetown Sierra Leone is developed from all of this, and as we make our way into the 1830s, that's partially how we get Liberia.

Lloyd: I am doing some research on that for another article I'm writing, and I must confess, while I've not finished the research, not a whole lot of people wound up being what you would call free.

Bridgette: Exactly.

Lloyd: It really was just that big a part of everybody who left. It wasn't a lot.

Bridgette: I just wanted to say this, since I did mention Governor Dunmore, who is the last royal governor who makes this offer, I think one of the things that I always try and stress to people is, realize when he comes out with this offer of freedom to able bodies of rebelled masters, it's not something he's doing out of the kindness of his heart. He's angry, and he had a reason to be angry. If we, today, put ourselves in his position, and say, OK, these people here are going against his mother country, they're saying that they're being treated – the patriots, people like Peyton Randolph and Jefferson – are saying that they're being treated as slaves, by his king. So, he's totally angry with the government, and the best way to get back at the Virginians is to hit them in their pockets. I say, why would you trust a man who's not offering freedom to his own slaves?

Lloyd: One of the things I researched was, why would Lord Dunmore do that, and it was revenge, pure and simple. You want to hurt me, I'll hurt you. And I can hurt you worse.

Bridgette: And, you know, if you were to the city of Williamsburg, I say, as an enslaved individual, you might really question his motive. Because, that was in November of 1775 that he made that offer. In just April that same year, he had accused you, the Negroes, of going into the gunpowder magazine and taking gunpowder out, and he had his own troops to go in and do it – with no muskets. I mean, like, what sense does that make, that you would go in and take gunpowder with no muskets?

Lloyd: It's not very helpful.

Bridgette: No.

Lloyd : That’s Colonial Williamsburg: Past & Present this time. Check history.org often, we’ll post more for you to download and hear.