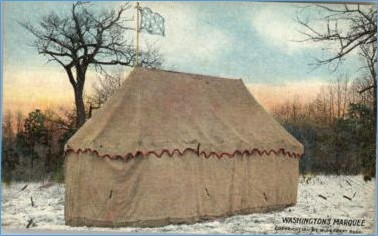

George Washington slept here, ate here, planned here, and plotted here through the eight years of the Revolution. A joint project with the Museum of the American Revolution is reconstructing the tent that Washington called home during the war. Learn more about the great man when you see his life in the field.

Podcast (audio): Download (18.3MB)

Subscribe: RSS

Transcript

Harmony Hunter: Hi, welcome to the podcast. I’m Harmony Hunter. We all know that George Washington was the first President. What we also all know -- even though we might think about it less -- is that before he was president he was a General fighting in a war that there was no assurance he would win.

Telling the story of George Washington as General is usually accomplished using maps and oil paintings, but a really fun and fascinating new project between Colonial Williamsburg and The Museum of the American Revolution is bringing new life to this story through a reconstruction of Washington’s camp tent.

My guests today are project leaders Mark Hutter, Supervising Tailor at Colonial Williamsburg, and Scott Stephenson, Director of Collections and Interpretation at The Museum of the American Revolution. Thank you both for being here today.

Mark Hutter/Scott Stephenson: Thank you Harmony. It’s great to be here.

Harmony: Well tell me how this partnership began. We’ve got two museums coming together to reconstruct a tent. Where did this idea begin?

Scott: Sure. So as Director of Collections for The Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia, we’re developing exhibition plans for this new museum that will be built in the Historic Area. One of the signature objects in our collection is the original sleeping and office tent, that marquis that George Washington used during the Revolution. It’s an object that descended through the Custis and Lee family; was acquired by the organization about 100 years ago, but it really had never been studied.

It’s very much like an old building where there are bits and pieces that may be missing from it, there are clues left in the textiles and so on. So we needed to pull together experts in different areas to really study this historic textile that’s also a piece of architecture. So it was natural to turn to Colonial Williamsburg.

I’ve known Mark Hutter for decades now and worked on other projects together. Initially it was a kind of research project and the reconstruction project has grown out of this effort to kind of study the tent, understand how it would have appeared when it was actually set up in the 18th century, how it functioned, how the space actually worked, how did Washington actually occupy the space within this tent.

Mark: We think of it very much like a building; a piece of architecture, but it’s a deflatable one. It’s a piece of canvas, and unfortunately unlike most buildings which are worthy of restoration, there’s enough original material that you can keep that intact and standing. In the case of the tent that’s not so. It’s now so fragile and the piece, the fragments of it, are scattered between diverse institutions.

There’s really no opportunity to ever re-assemble and re-erect Washington’s Headquarters as it would have stood in the field during the war. So our only opportunity to ever see what is home for the eight years of the war would have been is to reproduce it.

Harmony: This is such an interesting idea. You know you never think about, or I never think about, what Washington did in between battles, but he had a camp tent and it’s what you’ve been calling the first Oval Office. This was his base of operations.

Scott, you started to allude to the division of space in that tent and this is not your regular pup tent. Talk to us about how this tent was sort of engineered for the business of living and the business of running a war.

Mark: Well, perhaps we should clarify and actually say that these are really tents. We are currently working on one of two marquis that exist and together these two marquis, two oval tents, make up the headquarters. And then they are further divided within to have more room. So it’s a suite of tents that makes up the campaign or the field headquarters.

Harmony: A suite of tents. What did they need to do?

Scott: Well, so the tent that’s in our collection; this is the sleeping and office tent. It’s a slightly smaller by a couple of feet, you know, in height, width and length than the dining tent which was a sort of larger more open tent that you would have been able to bring groups in, you know, as suggested for meetings, dining and that.

This tent actually has an inner chamber within it, so it’s actually divided. It's about 22 feet long by a dozen feet wide, thereabouts. I mean, again, because you’re able to stretch these, an object made of a textile like this, it expands a little bit on all dimensions. But then within that tent, if you can imagine, there’s actually an inner tent that was about 8 x 10 feet. So the term we, we sort of use the terms tent and marquis sort of interchangeably.

In the period, the tent was actually that inner chamber and the marquis was the outer covering. So when that’s all assembled, it forms probably three distinct spaces within Washington’s sort of living tent. And one of the benefits of doing this reconstruction project is we can sort of set this thing up, we can play with different theories about how those elements interacted with one another. We’re still working out, “Well, how did this original inner chamber, when it was actually set up within the outer tent in our collection, how did that all work together?” I mean, there are still questions to be raised. In unison we have questions, yes. That’s right.

Harmony: Well talk to me about the documentation for this tent because if ever there was an ephemeral structure, it’s a tent. I mean, do you find plans for it? Do you find references to it? How do you know that you’re on the right track as you’re attempting this reconstruction?

Mark: Well, obviously we begin with the artifact or we should say the artifacts, the several pieces that are scattered between the collection of The Museum of the American Revolution, The Smithsonian and the National Park Service at Yorktown. So the study of the physical pieces is our first approach, but then there is certainly supplementary and supportive written documentation from within Washington’s own life and existence.

Scott and his team, for a couple of years now, have been ferreting out virtually every paper reference to the tent, both during the period that it was being built in the area of Reading, Pennsylvania and in its 19th and 20th century uses and context as well.

The tent is not unique in its form. These oval ended marquis are standard in 17th and 18th century into the mid-19th century military, European and American usage, and so thankfully we have other sources, military manuals of the period that illustrate and discuss the usage of tents like this.

One English book by an author with a French name, Lewis Lochée, provides some very useful illustrations and dimensions, which were very similar to Washington’s tent. He discusses those three inner rooms that Scott mentioned and in this case specifies that the inner most chamber, the square area, is to be the office.

The one round end outside of the office is the sleeping chamber and the other round end outside the office is to be baggage and storage area and sleeping space for any servants. We know that for much of the war Washington had his enslaved man with him by the name of Billy Lee and so while we think of this as Washington’s home, it may have been Billy Lee’s home as well. And so that sort of written evidence helps us to understand the use of the tent in ways that the physical object may not be able to provide.

Harmony: This is a tent, Scott, that tells us not only about George Washington’s life in the field, but also about kind of the engineering of battle and the waging of war in the 18th century. What have you learned about tents?

Scott: Well I’ll tell you, its…we’ve started calling this the other home of George Washington in that so much of our focus we think of Mt. Vernon as the home of George Washington which, of course it was, and the place that he took such great delight. But when I go back and sort of put my historian hat on and look back at the life of Washington, not just in this portion during the Revolutionary War, but if you literally go back to some of his earliest writings and experience, the diary he writes as a 16-year-old on his first surveying trip into northwestern Virginia, he spends a tremendous amount of time of his adult life under canvas.

You know, that experience during the French and Indian War as a young Virginia Colonel and again through eight years of the war of independence and then again just the following year after the peace appears, 1784, he goes to survey with his lifelong friend, James Craig, go look at his lands out in western Pennsylvania and the Ohio Valley, and hauls along quite possibly the very marquis that we are reproducing along with him for that trip.

So you do start to realize, the way that you live outdoors in the 18th century, it required a whole different set of accoutrements and ways of operating than working in the kind of reconstructed buildings that are so common here at Colonial Williamsburg, for instance. So in addition to reconstructing the tent, we are simultaneously working on documenting and in many cases try to replicate the pieces of campaign furniture that have come down through various lines of descent in the Washington family.

It will be a very unique experience to be able to see all of this brought together, replicated and put out on the ground and then eventually in The Museum of the American Revolution to actually come and see that tent installed so that you can actually see the original piece.

Harmony: It’s great to think that to really understand Washington you need to understand this part of his life and to see that life under canvas.

Scott: It’s important to remember I think as well, you know, it’s not…it gives sort of texture and human interest to Washington, but you could also think about this tent as, almost as a political item as well. Because at the end of the war, of course, there was great discontent in the Continental Army, there were fears that there might be a military coup at the end of the war, there was a lot of dissatisfaction with both soldiers and officers that they might be discharged with Congress not paying them off all the arrears in pay.

And of course there was the famous sort of called the Newburg Conspiracy in 1783 and this is when Washington, perhaps one of his greatest moments, steps up and addresses the officers and famously takes his eyeglasses out, and of course no one had seen him using eyeglasses, and says, “Gentlemen, you’ll forgive me, I have grown not just gray, but nearly blind in the service of my country.” Immediately, sort of in a sense, saving this fledging republic from the possibility of a military coup.

And Washington has that kind of authority because as he says in his speech, and also says in his later address to the troops when they are disbanded in 1783, unlike many general officers in the 18th century he remained in the field the entire 8 years of the war of independence. He is only at Mount Vernon for about 10 days in 1781, and it’s just because it’s literally on the road to Yorktown and back.

And of course during every winter campaign season Martha Washington would come and stay with him. And so he was able to say and look these men in the eye and say, “I shared the suffering and struggle that you did.” And that tent in a way sort of symbolizes his remaining in the field through the entire war.

Mark: We should probably add that, of course, there are a couple of dozen homes up and down the East Coast of the United States that rightly claim to have been Washington’s Headquarters at some time during the Revolution. And when the opportunity was there, Washington would request and pay for the usage of a home to provide a more permanent area, possibly a warmer and more secure area.

There’s a wonderful family record though written by George Washington Park Custis, Washington’s step-great grandson, who was supposedly told by a member of Washington’s life guard that even when the General was encamped in a house that he always had this tent set up nearby to serve as his private sanctuary, to retreat to, to rest and to write his dispatches. So to us this is very much his office; the first Oval Office.

Harmony: What’s next for this tent? You’ll get it reconstructed and it’s been a wonderful process. I should mention the reconstruction because we’ve been able to follow along on your blog and on a webcam as well.

Mark: And Facebook.

Harmony: And Facebook. What’s the address for the blog and the webcam?

Mark: You can find it all best if you simply search “first oval office” which is our address on Facebook. From that you can go to the blog which is hosted on The Museum of the American Revolution’s website and you can also get to the webcam which is hosted on history.org by Colonial Williamsburg.

Scott: Right, and even after the reconstruction process is over we’ll continue to host the first oval office blog. We’ll continue to add because we’re updating that constantly with research that we’re doing, sort of putting out the stories that we’re tracking together of the remarkable 19th-century history of how these tents were used and they were brought out when Lafayette returns 50 years after the Revolution and really have a very continuous and fascinating story of their use through the 19th century. So we’ll continue to update that even after the web cam goes cold for a while and the tent shop closes, so it’s worth checking “First Oval Office.”

Mark: But before that and the first public usage of the tent will be here at Colonial Williamsburg on November 16 at the official grand opening of the reconstructed Anderson Armory. On that day we will erect the tent there on the Armory site as part of our discussion and interpretation of Williamsburg’s efforts to prepare for war.

Harmony: I just can’t wait to see it. You think there’s nothing new to learn about George Washington. You think it must have all been said, but this really does show him in a different light and show, I think, a less examined part of his career and so it’s a wonderful project and I’m real excited to see it, to see the last knot tied in the thread there, Mark. Good luck to you.

Scott: Thank you.

Harmony: Look forward to seeing the project complete. Thank you both for being here today.

Mark/Scott: Thanks so much. Appreciate it. Thank you.