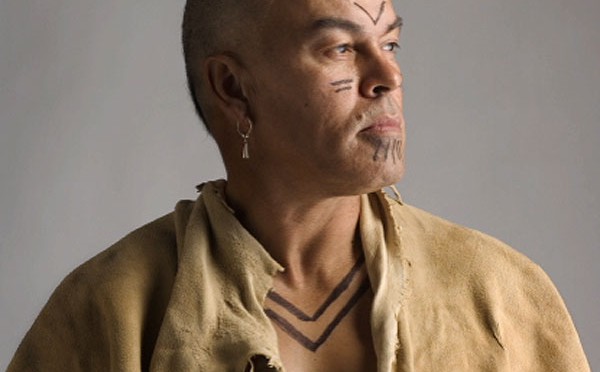

Stratified social organization, strategic alliance, and lineage leadership were hallmarks of Powhatan’s rule over southeastern tribes. Buck Woodard describes the society that existed before first contact.

Podcast (audio): Download (2.4MB)

Subscribe: RSS

Transcript

Lloyd Dobyns: Hi. Welcome to Colonial Williamsburg: Past & Present on history.org. This is “Behind the Scenes” where you meet the people who work here. That’s my job. I’m Lloyd Dobyns and mostly I ask questions.

When America’s story is told, it usually begins with the settlers: men brave enough or desperate enough to cross an ocean to get a new job. But America’s story begins well before the first attempts at colonization – native tribes occupied the acres that the English counted as wilderness. Buck Woodard is here to tell us more about the indigenous people of the New World.

How many of them were there? Do we know with any certainty?

Buck Woodard: No, we don’t know with any certainty how many there were before contact. It ranges wildly in terms of numbers. At the beginning of the 20th century, estimates were 2 million, something along those lines. Here in Virginia specifically within the boundary that we call Virginia, if we were to maybe think of it as the Chesapeake region, get rid of the political boundaries of Maryland and Delaware, and North Carolina, we might consider 10,000, 12,000 people in the Tidewater.

Lloyd: So a big empty place, it really wasn’t.

Buck: No it wasn’t. It’s all relative. You know, how many people live in the same space today, compared to how many people lived in those places in the past? But we’re really talking about different points in time, different types of resources, different social organizations, different complexities of communities. There’s areas in the Southeast and the Midwest where are huge metropolises that had 30, 40 thousand people living in a very small and dense area with a high amount of social organization with people who are very powerful at the top and people who are quite subservient and worked at the bottom, and a lot of range …

Lloyd: Pretty much like today.

Buck: Yes, and a lot of range in between. So the Americas was not without those types of organizations, and cities, permanent structures, monumental architecture. But here in the Atlantic Seaboard, it was much, organized much differently. Not every place in the New World, as it has been called, had the same level of organization or development through time, much like it is around the rest of the world as well. Things rise and fall, whether they’re Mayans or Egyptians or Romans and the like.

Lloyd: So you’ve got, there are, there is, a society here before the Englishmen arrive in 1607.

Buck: Very much so.

Lloyd: What kind of society?

Buck: The groups here were fairly organized as what we might think of as chiefdom complexes. They had individuals in the society that clearly had more access to resources than others, you might think of them as elites. They came from distinct lineages, and those lineages were known, and those lineages, usually they passed down that level of wealth or status or position through the bloodlines from one generation to the next.

There’s also a portion of the population that we might think of as commoners, or different groups of lineages that don’t have that distinction. The society is stratified so that we have higher people at one and lower people at the bottom. They have differential access to resources, whether it be skins, furs, shell, certain types of feathers or paints, certain types of foods, non-seasonal foods. For instance, having corn all year round, even when it’s not being grown or in season coming in fresh.

So the groups that were here, we call them chiefdom complexes because they seem to be in a period of change at the time of European contact. Going through a lot of stress and shifts in population. One of the reasons why it’s thought that maybe there’s only 10 or 12 thousand people in the Tidewater is because it’s recently gone through a series of epidemics, because of European contact in the past hundred and some-odd years. But also because one individual today who we most popularly refer to as Powhatan began expanding his political dominion over a large portion of what is now today Virginia, Virginia Tidewater. We call that political organization that he formed “The Powhatan Paramount Chiefdom.” Which is bringing in smaller polities, collecting them together to make one larger polity that he governed over the entirety of it.

Lloyd: I’ve heard, seen him referred to in various books sometimes as king, sometimes as emperor. Is either one of those titles sort of appropriate, more or less?

Buck: Well that’s how the English described him, and I think they were attempting to make sense of what they saw. They paralleled a monarchical government of England with that they seem to think of as a monarchy in Virginia. He was a lineage leader, Powhatan was. His proper name was Wahunsunacock, and he was born in a place called Powhatan. Powhatan was the territory, the lands that was known by that name, a series of villages up around the falls of Richmond, falls of Virginia, a place called Richmond. He took that name from his native town when he rose to power and prominence in that region as a lineage leader.

It would seem, some academic research suggests that it was a marriage alliance between what is the James River drainage and the York River drainage some generations before Powhatan’s birth that allied two groups of people that lived on these river drainage together. So that the English say Powhatan inherited six districts, or territories: so six different. We thought of them as different groups, but maybe it might be really lineage, dominant lineages and use lands in certain areas. He inherits them as the weroance or the lineage leader, the dominant lineage leader over all of them.

So when the English meet him, he’s expanded that territory, let’s say he comes to power in 1565, 1570. By the time the English come and set up Jamestown in 1607, he controls not six groups, but what we think of probably around 30. So he’s really expanded his influence and his dominion through coercion and partnership of various kinds over much of the Tidewater Virginia.

Lloyd: So as the paramount chief, all the other chiefs do what he says, or maybe and maybe not?

Buck: Not always. They don’t always work together. You have to, I think, realize the political theater of the period. Powhatan expands in 35 years, into territories that his family never previously controlled. So we have to ask, well how did he do that? Was it military? What kind of offers did he make people that they couldn’t refuse to become part of his organization?

In the early records, it’s pretty clear that not all weroances, or chiefs, are willing to do what Powhatan says. In some cases they do, in other cases they don’t. They all pay him tribute, some of them willing. I mean, tribute – they send him, they collect tribute from their villagers and they send tribute from their communities up the pike to Powhatan. One tactic that he uses is that he makes various strategic marriages across the tidewater, so that he has quite a few wives by the time of 1607. They say upwards of 100 children. Pocahontas is probably the most famous daughter, is just one of those children.

So one way in which he could exert influence and control those territories and to make groups fold is to make strategic marriage alliance so that the next generation of children are loyal to both him and to their original lineage. So also for the first time in Tidewater, one man is related to the elite members of almost the entire region we know today as Virginia. One man. He’s related to all of them.

Lloyd: It’s very hard to fight a relative.

Buck: Yes. It is. So when the English arrive, they take note that Powhatan’s sons are chiefs at a number of locations around the James River area. He’s married to a number of women from the Appamoatox area. He has apparently sent a daughter to live among the Potomac region. He has all these different elite arrangements and alliances that appear to be unfolding very recently in time. The English see that as being akin to what they know of as the royals in England and the people of status in their own background. They accord those titles of kings and queens and they think of it that way.