By 1820, the original Declaration was showing signs of wear. John Quincy Adams commissioned a now-famous facsimile. Librarian Doug Mayo describes Colonial Williamsburg’s copy.

Podcast (audio): Download (8.6MB)

Subscribe: RSS

Transcript

Harmony Hunter: Hi, welcome to the podcast. I’m Harmony Hunter. This week we’re talking to Doug Mayo, Associate Librarian at the John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library. Doug, thank you for being here with us today.

Doug Mayo: You’re welcome.

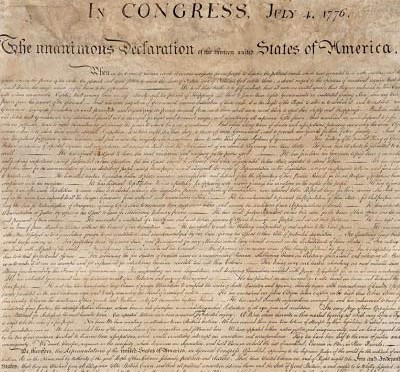

Harmony: You’ve come to talk with us about a rare surviving artifact of the American Revolution: the Stone Declaration of Independence. What is that document?

Doug: Well actually, it’s a version of the Declaration of Independence that was a generation later. So it’s not actually from the time period of the original Declaration of Independence. It’s from the 1820s. It’s a commemoration of the original Declaration of Independence.

Harmony: What is the story behind the Stone Declaration of Independence? Why did we need to do a reprint?

Doug: Well, even by the eighteen-teens, the original Declaration of Independence was starting to deteriorate. There was starting to be ink loss. It was starting to fade. It was decided that there needed to be a copy that could stand in, in a sense, for the original Declaration of Independence.

Think about what had happened to the original Declaration of Independence. It’s written in 1776, and during the American Revolution, it travels a lot. Every time the American government has to move because the British get close to the Congress, the document gets moved. In fact, it takes quite a bit of time before things settle and the document is allowed to stay in one place for a large period of time.

Even thinking back during the War of 1812, when the British come in to Washington, the document has to move at that time, too. It continues to move throughout the 19th century into the 20th century, until it finally finds a permanent home at the National Archives.

Harmony: I want to talk about the materials. You mentioned that there was ink fading. What type of paper was it printed on? Why did the ink fade?

Doug: The Declaration of Independence was actually handwritten on parchment. We believe it was handwritten by a man named Timothy Matlack. He had assisted Charles Thompson, who was the secretary of the Continental Congress. Matlack is the man who had written out the commission for George Washington.

But over time, documents that get rolled and unrolled continually – every time some visitor comes to Washington and wants to see it, it is unrolled and then it’s rolled back up. And then there are periods of time when it’s exposed to light. Light, over time, is going to have a negative impact on any document written in ink.

Harmony: I read somewhere that the ink, the formula for used when the Declaration of Independence was written included a component of iron. So the sort of rusty color that we see when we see a picture of the Declaration today is not the color of the ink it would have been written in at the time, but that’s an effect of oxidation.

Doug: It would be age. There could be some acidity to it as well. It could change the paper, or the parchment, in this case, as well.

Harmony: Even if you’re seeing it today – if you go to the National Archives and see it – you’re not going to see it the same way. It’s not going to look the same as it did.

Doug: No, in fact there’s very little of it that’s legible now. It’s in very poor shape, unfortunately.

Harmony: Hence the need for a copy. Who commissioned the Stone Declaration, the Stone reprinting?

Doug: The Secretary of State at that time was John Quincy Adams. He had actually been approached by another man by the name of John Binns. Before the government commissions an official version, there are other men who are creating copies of the Declaration of Independence for sale. Now, these copies that they’re creating are not exact facsimiles of the Declaration of Independence. Some are put out by men who are calligraphers. So they are changing the way the text looks.

Some are put out by, for instance, John Binns. He makes a very elaborate frame which has George Washington’s portrait, as well as that of Jefferson and Hancock and the 13 state seals which surround the text. So these productions are being put out there for sale with the intention that people will hang them up in their homes and display them. John Quincy Adams is approached by this man, John Binns, and Binns wants Adams to purchase 200 of his copies for the government. Adams instead turns to William Stone, and commissions Stone to create an exact facsimile that will then have 200 copies printed which will be at the disposal of the government.

Harmony: How do you do that before copy machines?

Doug: Well, what Stone does is – and let me clarify that we’re not exactly sure what Stone does – we know that the process involves a copper plate. So he’s creating an engraving. He’s essentially taking a document that’s handwritten, and then he’s going to create an engraving of it on a copper plate.

Harmony: Meaning that he’s going to try to exactly trace the original document, but in copper?

Doug: Right. What that process entails is actually doing it in reverse. Because when you then print from that plate, when you turn that paper around, then you’ll be looking at it correctly. It necessitates him essentially copying 57 hands. When you think about it, the document is written in one hand: Timothy Matlack, we think. And then signed by 56 members of congress. The process takes about three years.

There’s no contemporary account of exactly how he does it. Now a lot of people think that what he did was called a wet transfer process, whereby he took a sheet of paper that he dampened, placed on the original to remove some of the ink, and then transferred that ink onto his copper plate. Now, that story actually first appears in 1881. So there is no proof that supports that story, though it is possible that that’s what he did.

Harmony: How else could he have done it?

Doug: Well, he could have done it by simply, laboriously learning those scripts and copying them on to his plate. Well there may have been several other techniques at the time period that he could have used, but that wet transfer process was something that was very common back then.

Like I say, we’re not entirely sure what he did. The report that came out in 1881 is some 60 years after the fact. So we’re never really going to know for sure. Though there was a group of conservationists who looked at the document and decided that they couldn’t see any evidence that a wet transfer process had taken place.

Harmony: Did he do a good job, when you compare the Stone copy against the original, are they close?

Doug: Definitely. It’s very hard to compare, now. Because again, that original is so faded.

Harmony: How do you know a copy of the Stone Declaration when you see one, if it’s such a close copy of the original?

Doug: Well because Stone left an imprint.

Harmony: He signed it.

Doug: So essentially it says that it was done by Stone, and it was done for the Secretary of State, John Quincy Adams.

Harmony: So these copies were printed in 1820, you said?

Doug: About 1823.

Harmony: The 200 copies were printed in 1823.

Doug: Right. Actually 201. Stone was asked to do 200, he did 201. It was very common to make a copy for himself.

Harmony: Where is that copper plate today, has that survived?

Doug: That’s at the National Archives.

Harmony: So we have in 1823, 201 copies printed. Where did they go out into the world? How many are accounted for now?

Doug: There’s about 31 that are accounted for now. There was an elaborate plan as to how these would be distributed, the 200 copies that were commissioned. They were supposed to go to the various departments of the government, to the various states and to some of the universities at that time, as well as the president, the former president, the vice president and the signers who remained at that time, of whom there were three. At that time that that plate was printed from, there would have been three signers: Thomas Jefferson, John Adams, and Charles Carroll.

Harmony: So we have 31 surviving copies. We’ll fast-forward to the present day –we have today in the collections of Colonial Williamsburg a copy of the Stone Declaration. How did we come to acquire this really rare artifact?

Doug: The Stone Declaration came to us in 2001 from a couple in California: the Epsteins. In fact, what they have placed here at Colonial Williamsburg is a larger collection that also includes something signed by every signer of the Declaration of Independence. Also something signed by each one of the presidents up through Ronald Reagan. So it’s part of a historical document collection that they’ve put on loan here at Colonial Williamsburg with the understanding that one day it will be a gift.

Harmony: How do we take care of a document like that? If the original Declaration was so susceptible to air and moisture and light, how do we take care of this one?

Doug: Essentially what happens in a museum setting is, temperature and humidity are controlled. That and the light are the most important thing. The Stone Declaration is actually on exhibit right now. If you go and you view that document, once you enter the space where you can view that from, a certain amount of light comes on. After a certain amount of time, that light goes off. So it’s set up to minimize the amount of exposure.

The Declaration, the Stone Declaration will not be permanently exhibited. It will come down and then it will be put in a vault in special collections where the lights are only turned on if somebody’s going back there to retrieve materials.

Harmony: What strikes you about this document when you look at it and when you hold it?

Doug: Well I’ve never actually held it. It’s been in a frame ever since I’ve been responsible for it. When I look at it, what strikes me about it is two things. First of all, it evokes the circumstances in which it was created -- that American struggle in 1776 to free ourselves from the British.

The other thing about the Declaration of Independence though is the fact that it has universal appeal. It’s not necessarily just about that moment in 1776. When you read that “We hold these truths to be self-evident that all men are created equal,” that is not a statement that applies just to Americans. It should not be a statement that applies just to Americans, it should apply to all humanity. It’s a very moving document.

Harmony: You mentioned that it’s on exhibit now. Tell folks more about how and where they can come see it.

Doug: It’s at the DeWitt Wallace Gallery at Colonial Williamsburg.

Harmony: Doug, thank you so much for being here with us today.

Doug: You’re welcome, thank you.