The first combat submarine was invented as a vehicle to transport underwater bombs. Jerry Roberts of the Connecticut River Museum tells the story of an intrepid American inventor.

Podcast (audio): Download (11.2MB)

Subscribe: RSS

Transcript

Harmony Hunter: Hi, welcome to the podcast. I'm Harmony Hunter. 1776 was a year of rebellion and a year of invention for America. It was in September of that year that the first combat submarine saw action in the waters of New York Harbor.

The sub was called the Turtle, and our guest today is one of four experts in the world on its creation and its operation. Joining us now by phone is Jerry Roberts, Director of the Connecticut River Museum. Jerry, thank you for being with us today.

Jerry Roberts: Glad to be here.

Harmony: Well we're talking about the Turtle. This is not the first submarine in the world. What kind of first was this for America and for the Revolutionary War?

Jerry: Well, you know, it is often counted as a first successful submarine in the world. There were some submarines earlier that really weren't submarines. The were sort of covered boats that they managed to force underwater temporarily, but this is the first modern submarine as we know it that truly had functioning ballast tanks and pumps and navigation equipment and really worked as a submarine.

Harmony: Who's our inventor here?

Jerry: David Bushnell, who was a fellow who lived right nearby here. His father was a farmer. He had a younger brother named Ezra. The father died and left the farm to David, who was the elder son. But David wasn't interested in being a farmer, so he sold his half of the farm, or he sold his interest in the farm, to his younger brother who did want to be a farmer and David went off to Yale. He was a very inquisitive fellow, he was in Yale, and that's where he got exposed to the whole concept of underwater explosives.

Harmony: And underwater explosives were his true interest, not so much submarines?

Jerry: That's right. He didn't set out to invent a submarine at all. He was fascinated with the concept of exploding. At that time, of course, they were using black powder and many people didn't think that that would explode underwater. People thought that if you tried to do an explosion underwater that the water would immediately extinguish the explosion and it would have no effect, but while in Yale he was exposed to other people's experiments in all of the library resources there and he began to do experiments.

He found if you took a small canister of black powder and you set it next to, like say, a rowboat and you exploded it, it really didn't do any damage to the boat because all the force of the explosion would go off sideways. But if you placed it right underneath the hull, the explosion would bounce off the shock wave that was created in the water and break the hull of the boat and so he figured if he could get a keg of gunpowder underneath a major warship you could damage it.

Of course, we were ramping up for the Revolution. He knew very well that we did not have a large and powerful Navy and England certainly did. The only way to, perhaps, even out some of that score was to come up with this very, very high tech way of attacking a ship. And so, once he perfected his under water bomb he had to figure out how you get that underneath the warship. So now he had to invent the world's first practical submarine.

Just before they were going to attack the British in Boston, they were going to take it from here up to Boston, they found out something that put a damper on the whole project. This thing was designed to attack British ships at night under water, so it's going to be pitch black. So to navigate under water you had to have a depth gauge and you had to have a compass, but to see those things you couldn't light a candle because that would burn up your air. You only had a half an hour of air inside this little submarine.

So they asked many people, including Benjamin Franklin, who was the leading scientific mind of the day, "what's the best system to use?" And the best system to use was something called foxfire. It's basically sort of a fungus that grows between the bark and the trunk of fallen, rotted trees. If you pull back the bark of a rotten tree in the forest you get this green glowing effect for a while. I personally never have seen it, but apparently it was a well-known fact.

So they would collect this foxfire in a little tub inside the submarine and smear it around the compass and the depth gauge and it would glow kind of like a glow stick, but they found out when they were ready to attack the British in Boston it was winter time and they found out that foxfire will not glow in the winter. It won't glow when it's that cold. So the submarine couldn't go to Boston to attack the British for that simple reason because this fungus doesn't glow in the dark in the winter.

The next opportunity came when the British had left Boston and had now surrounded Washington's forces. Washington was in Manhattan. He had already lost the Battle of Brooklyn Heights and now the British had 400 ships in New York Harbor preparing to cut off Washington's forces in Manhattan and pretty much end the war at that point. So Bushnell was asked to rush the submarine down to Manhattan and the feeling was if this little submarine could go out into the Harbor and attack the British flagship, HMS Eagle, which had Admiral Lord Howe aboard, that that would at least delay the British onslaught on Manhattan enough so that Washington could reinforce his troops or whatever.

So they rushed the submarine down there and were preparing to launch it. George Washington was aware of this. I don't know if Washington actually believed it would work, but he figured anything was worth a shot. And just as they got down there, and they were living in close quarters with all the thousands of American soldiers in Manhattan, camp fever was going around the troops. People just got sick from living close together. Ezra Bushnell, David's younger brother who was the only trained pilot, became deathly ill with this camp fever.

So now you've got the Turtle in place, the British in place, the clock is ticking, but you don't have a pilot for this world's first submarine. So they ask for volunteers and three men came forward. The one that was selected was fellow named Ezra Lee, who was also from Connecticut. They trained him for a week and in that week he probably got four or five or six dives in this submarine and then they rushed him back to Manhattan. Now, this fellow who had never stepped inside a submarine, probably not even a serious boat before in his life, is going to row out into New York Harbor and attack the flagship of the world's greatest Navy.

Harmony: I think now might be a good time to talk about what this submarine looks like. This is not the cigar-shaped vessel that we're used to seeing now. It's like a walnut shape.

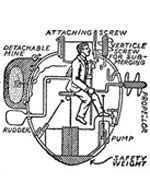

Jerry: That's correct, and that's a very, very good analogy as a walnut. It was about, let's say 6 feet high and maybe 6-7 feet in the longest part. An almond shape is, again, a way to describe its shape. Little bit more streamlined than a walnut. Think of an almond perhaps, and maybe about, let's say, 4 feet at its narrow dimension.

So he would climb down into this thing through a brass hatch on top. There was a very, very cleverly built brass hatch which could be sealed down. He would propel himself with a propeller and it was believed to be the world's first operational propeller, which is a key to this story later on. So a propeller would make him go forward and backwards. He had a tiller that passed through a watertight gland and had a rudder on the back of the submarine.

He had another small propeller for going up and down. He then had a ballast tank that he could let water into the submarine and that ballast tank really let water in just beneath his feet into the bottom of the sub and that he could pump that out. He had a rudimentary snorkel system so that on the surface if a wave went over the top of the thing he could breathe and the snorkel would close itself, but during the attack he had to close everything down and he just had the area inside.

And then the key to the operation was there was this big, imagine something the size of a barrel, but much more substantial than a wooden barrel that had probably 3-inch thick sides and 150 pounds of gunpowder in it, and there was the flash pan for a flintlock pistol was in there, as well as a timeclock. So this thing was strapped out of the back of the submarine and then a rope led to an auger.

So from inside the submarine he could turn a crank and drive this auger up into the hull of an enemy ship. Once the auger is stuck in the wood he could release the auger and he could release the bomb from inside the submarine so he would then pedal away for his life while this time clock ticked away. Now the barrel is floating up against the bottom and after an hour it would go off. So that was the system.

Harmony: How did it work?

Jerry: Good new and bad news. The submarine performed flawlessly and he actually did three, there were three missions. He took two of them and another man took a third. But during the three missions and the classic one was the first one. Now think of it. It's night. It's pitch black. You've got all these British ships out there with guard boats rowing back and forth in between them.

So a rowboat would pull him from the battery of Manhattan out into the British fleet and the rowers with muffled oars would get as close as they dared to the fleet, several hundred yards I imagine, they would cast him loose, he would then pedal on the surface and on the surface about two feet of the submarine are sticking up, and they've probably got black tar spread over the brass so it's dark.

So he's got to now, with his own body power, crank and steer this thing. He got caught in the current and taken away from the British fleet so it took him hours and hours to get into position again. So he's been pedaling out there for like five hours. I mean, just imagine how exhausting that is inside of this dank little wooden thing. He got to the Eagle, he submerged, got underneath the Eagle, but try as he might, he could not make the auger bite into the hull of the British ship and that was the failure. They were never able to get this auger, this screw bit to go into the hull of the ship.

Jerry: He finally after trying as hard as he could he popped to the surface, the British saw him, he pedaled away as quickly as he could. They put boats in the water to chase him not knowing what he was. He let go of the bomb, as a diversion. It exploded, which fortunately scared all of the rowboats back to the ships and he was able to escape. They tried this twice more within a month. Each time the results were similar. It's amazing that he escaped with his life, but the submarine itself performed perfectly. The bomb delivery system did not.

Then the British did take Manhattan so Bushnell and his support crew moved the submarine further north up to approximately where the Tappan Zee Bridge is now and the British did a sweep up there to get all the American ships out of the Hudson and during that sweep they sank the little sloop that the Turtle was tied to. The British didn't even know that they sank it. They just sank all these sloops. But the submarine wasn't hurt. It was quickly recovered and Bushnell brought it back here where it was built, put it in the barn of his brother's farm where they built it, and saved it for a better opportunity, which never came.

The documentation we have on the submarine is that after the war Thomas Jefferson became our Ambassador to France and in the 1800s he was over there, in 1783. He was in France, the French were touting a demonstration of the world's first propeller-driven rowboat. Jefferson sees it and says, "Wait a minute, I think we had a propeller during the Revolution," and he writes back and says, "Find this guy Bushnell and I want a report on his invention of the Turtle because I think the Americans invented the submarine."

It took a year for Bushnell to be tracked down and answer Jefferson. Fortunately when he answered Jefferson he sent this long, long letter telling him everything that he knew about how he built the sub, including dimensions and technologies. No drawings unfortunately, but very detailed descriptions and then he'd also give a very detailed description of the three missions and he ended his letter with, "After it was sunk on that sloop he recovered it and prepared it for a better opportunity that never came."

So we know that the Turtle was still sitting in a barn in 1800 and then it disappeared. The house that his brother owned is still standing. The barn is gone. No one knows what happened to the Turtle and every reproduction, and our museum has two of them, that have been made of the Turtle have been made by painstakingly studying every single word of Bushnell's letters to Jefferson and trying to interpret what that meant in three dimensions.

Harmony: Do you still hope you'll find the original someday somewhere?

Jerry: It's one of those fantasy things that I'm sure the whole Turtle isn't sitting anywhere. It's a pretty big solid thing. We think the submarine was six inches thick. You know, it was broken up for firewood or rotted away, but the bronze hatch system that was quite elaborate was cast bronze, like a bell. Unless someone purposely destroyed it, it would have survived anything.

God knows, wouldn't it be great to find that propeller in somebody's attic or one of the two propellers. There are a couple of pieces associated with the Turtle. There's a piece of what we believe was a depth gauge or a timing device that the Connecticut Historical Society has. No one's quite figured out how it would have fit on the Turtle, but they're associated with the Turtle. But yeah, we also tell school kids when they come here that make sure you look in your attic because you never know what you might find.

Harmony: It's hard to pick what the best part of this story is. You have a wonderful engineering imagination, bravery, battle. What's your favorite part of this story?

Jerry: I like the fact that this is a classic example of Yankee ingenuity. This wasn't a government project. This wasn't NASA. This wasn't the Navy. This was a guy and his brother and a couple of friends who made this happen and then the fact that the man that was trained to do it for a year couldn't do it and the fellow who carried out these missions was a foot soldier who volunteered.

It's like volunteering to go on the first Mercury space capsule one week before the mission. I just can't imagine the bravery of getting down underwater in the blackness of a submarine all alone in New York Harbor against the biggest fleet on earth. Who would volunteer to do that?

Harmony: If people want to come see these replicas, tell us where they can find your museum.

Jerry: Sure. We're in Essex, Connecticut and Essex is a beautiful little town. We have an extensive exhibit about the Turtle including interactive electronics where they can basically learn all the mysteries. So we're open year round. We have a website – www.ctrivermuseum.org. So it's a great place to visit.

Harmony: Jerry, thank you for sharing this story with us and I hope that listeners who get up towards Connecticut will stop in and see your museum and the replica of the Turtle. Thanks so much.

Jerry: Thank you!