The Indian School at the College of William and Mary was conceived for the religious conversion of Indians. Professor Jim Axtell shares the storied building’s history.

Podcast (audio): Download (9.0MB)

Subscribe: RSS

Transcript

Harmony Hunter: Hi, welcome to the podcast. I’m Harmony Hunter.

When colonists first landed on Virginia’s shores in 1607, they thought they were entering an uninhabited wilderness. What they discovered was a complex native society.

In the years that followed, English colonists struggled with their relationship with native people: sometimes making alliances and friendships, and sometimes going to war with them.

In 1723, the colony built an Indian school whose mission was to propagate the Christian faith among the Indians, so that young students who were taught there would return to their tribes and become missionaries by proxy, converting their kinsmen to Christianity as well.

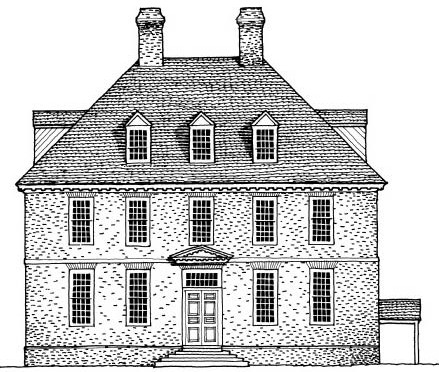

The school was called the Brafferton, and it still stands today on the historic campus of the College of William and Mary. My guest today is Kenan Professor of Humanities Emeritus at the College of William and Mary Jim Axtell, who has spent a good part of his career studying the history of European and Native American interaction. Jim, thank you for being with us today.

Jim Axtell: It’s nice to be here.

Harmony: Can you talk about the first contact between native tribes and European settlers? Who was here already and how did those first interactions go?

Jim: Well the Indians who were in the Virginia area, especially along the James River and between the York and the James and south of the James, were the Powhatans.

They were named after their paramount chief, but you’re really talking about 32 tribes that he had put together from the late, the last quarter of the 16th century by conquest, by diplomacy, by inheritance. He inherited only six of those tribes and then put together the rest into the second-most powerful confederacy in North America.

It’s exactly the wrong place for European colonists to try to settle. Because he’s on the muscle, he’s conquered recently all kinds of people around him, and the riverine character of the colony makes it extremely difficult to defend.

Harmony: When we say that a colony built on the river makes the colonists vulnerable to attack by Indians, the underlying assumption is that the relationship between the Indians and the colonists is a confrontational one.

Jim: What you have to remember is that both of these groups are farmers. They live primarily by agriculture, both the English and the Indians. So they have already figured out where the most fertile lands are, which tend to be up and down the rivers and between the rivers. And the English, when they come, they belong to an economic company that’s trying to make money for its stockholders.

They, if they’re going to make plantations, they’re going to have to have the best farm they can get. So there’s an inevitable conflict over the best farmland in this part of the world. So Powhatan doesn’t really have much use for the English.

Harmony: In 1607 when colonists first arrive, the advantage definitely lies with the Powhatan people. By the time we get to 1723 when the Brafferton School for the education and the Christianization of Indians is built, their numbers have dwindled almost to nothing, while the European population has grown exponentially.

Jim: By 1723, or even earlier, by the time William and Mary is established in 1693, the Indian population is drastically reduced from something like 13,000 to maybe 1,000 in the colony proper.

When the Rev James Blair, a big political figure, a major religious figure in the colony, goes to London to try to obtain a charter for a new college in the colony, at that point there is only Harvard, way up in Massachusetts. So he is trying to have Virginia have its own college.

But in 1691 he’s over there lobbying Parliament and all kinds of bigwigs, he hears about the death of Sir Robert Boyle, who was a great scientist, great chemist, an important man a member of the Royal Society of London. He leaves a big estate, 5,400 pounds. It’s for charitable purposes of various kinds. So Blair marches up to the trustees of this charity and tries to sell them on an Indian school.

He gets the trustees of the Boyle fund to give him – and to share with Harvard which has its own Indian school by then – half of the money that comes from an estate. The Boyle people have bought a big estate in Yorkshire called the Brafferton. The profits again from that, the tenants and so on, are now brought together for charitable purposes and split between Harvard and what becomes William and Mary. And so he is perfectly happy with that.

Now from 1691 when he gets this money promised to him to 1711 when they get their first students, this fund is building up. And they’re not spending it, they have a fair amount of money by the time they get their first students. In 1712, there were 24 students, which is extraordinary in number. In the 1720s, the numbers drop off drastically. The students realize that this is not for them and so on.

Harmony: This is an interesting point I wanted to bring out. Can we talk a little bit about what the European goal was in educating these Indian students, and then what did the Indians really get out of it? It wasn’t what the Europeans intended.

Jim: No. From the English point of view, when you land in the midst of this big confederacy, you’ve got two problems. One is, the Indians think differently. You don’t understand how they think and you can’t predict how they’re going to act, because of their cultural background and their own goals.

Secondly, they are dangerous, because Indian warfare is guerrilla warfare. It’s not conventional European warfare. You don’t know when they’re going to strike, it’s all based on surprise, and they have certain military customs like scalping and torture and a variety of other things that scare the heck out of the Europeans with perfectly good reason.

So from an English point of view, one of the ways to make the Indians more predictable is to convert them to English ways of thinking. And that’s what they hoped they could affect amongst these unpredictable dangerous unreliable neighbors of theirs.

Harmony: But the Indians were not interested in that.

Jim: The Indians were not interested in that at all. They don’t want to be predictable.

Harmony: They were able to use the Brafferton as a course in studying their enemy.

Jim: Exactly. There are lots of skills the Indians can pick up. One of them is literacy. If you have the ability to read and write and you come to a treaty in the back woods with the English diplomats and they pull out this piece of paper and make you sign it and so on, if you have literacy, you can discern what that says and you don’t have to rely on the English memory or version of what it says.

Secondly, if you learn elementary mathematics, mostly arithmetic, you can avoid being cheated by English traders who have their own little account books and this is a way for the Indians to have their own accounts. They already knew how to count, they already had tally sticks and a variety of other ways of keeping track, but it was to their interest to be able to read the English account books to make sure they weren’t cheating them in that way.

Thirdly I guess, the English religion, Christianity, had some benefits for some Indians. If your culture is being smashed by disease that’s inexplicable, if you are being beaten on a regular basis by English armies or If English technology seems to be superior, you might wonder if the English don’t have something, some superior backup. Some way of explaining the universe, some way of manipulating the universe.

And so several Indians, many Indians looked to the English religion for some assistance in their own problems. They thought if they could buy into the English god, that god would protect them from epidemic diseases the way they protected most of the English from those diseases.

Is that a success? No it’s not, because the kids died in rapid numbers from urban diseases, from unfamiliar clothing, from unfamiliar houses with fireplaces that overheat you in one part of your body and freeze you in another, unfamiliar food, racism amongst the other students or their parents or people in the street. And the curriculum is totally strange and mostly ridiculous from the Indian’s point of view.

So they run away if they don’t die. We have lots of accounts of them being cared for by doctors. Of course, the medical practices of the day are so terrible that they killed most of them with the so-called cures or the medicines, or they ran away. Some of them walked home 300 miles eating acorns and fruit and crossed the James River somehow to get back into North Carolina amongst their people.

Harmony: The Brafferton tells us a troubling story about our nation’s past and our history. When we look at that building, what should we learn from that?

Jim: It’s a great building but you have to remember it was only used as an Indian school for 60-some years, 66 years. It closed in 1777 as a result of the Revolution.

It’s an attempt, but if you look at all of the motives and not just the pure ones, not just the benign ones like giving you Christianity, giving you civilization, Like all of those early attempts at benign conversions, it’s a very mixed bag. It’s mostly unsuccessful.

You could argue on both sides whether it was harmful or helpful to the Indians who attended. Most of them wouldn’t have said it did them much good. But a few used its lessons, as we said, to fight their own good fight when they got home. Rather than being emissaries of the English and helping further conquest and colonization. They used it for resistance. So that’s a complicated story there.

Harmony: Jim, thank you so much for being here with us today, it’s been a pleasure having you.

Jim: Thanks a lot.