Myths abound in history’s retelling. Historian and author Mary Miley Theobald shares some of her favorites.

Podcast (audio): Download (8.9MB)

Subscribe: RSS

Transcript

Harmony Hunter: Hi, welcome to the podcast, I’m Harmony Hunter.

My guest today is Mary Miley Theobald an author for the Colonial Williamsburg Journal who has made a study of some of the persistent myths in history and the struggle of historians to keep a balance between fiction and nonfiction in historical interpretation. Mary, thank you for being here today.

Mary Miley Theobald: Oh, you’re welcome.

Harmony: Now some of these myths are a lot of fun and I think that might account for their longevity in some cases but why else do you think these are stories that keep getting repeated?

Mary: Mostly because they’re either humorous or shocking or in some way catchy and the stories stick in our memories when maybe some of the less sexy information slips away.

Harmony: What are some of the myths that you uncovered and what you discovered about them?

Mary: One that you hear that is very persistent is that fire screens were put up between a woman and the fireplace to keep the heat from the fire from melting her wax make-up.

Harmony: Now when you say fire screen what does that look like?

Mary: It is a flat piece of wood usually decorated with some sort of needlework that is on a stand and sits next to the fire. Actually fire screens were fairly unusual in household inventories, which are lists of the possessions made after a persons death. In inventories there are very few fire screens in American homes. It was an expensive accessory, something that that showed off a woman’s needlework skills. But it was placed by the fire for use by men and women to shield them from the direct heat, no one’s face was in danger of melting.

Colonial American women wore little or no make-up at all and this was something that Europeans noticed and commented on whenever they visited America because make-up was more common in Europe among upper-class ladies, where they had come from. But in America they found that that this was not something that the ladies did.

Plus, when you look at 18th century housekeeping books where they give recipes and medicines and and household tips, there are some recipes for skin care but these are skin treatment, something that was intended to be applied and washed off and not a single one of these uses wax.

Harmony: So we also run into one frequently about the length of beds often that bed length is short because people were short.

Mary: Well this is a really old one, it was around at least in the 50s. Curators and historians have been trying to squelch this for decades without much success, I’m afraid to say. There are really two issues here. First of all, colonial-era beds were made individually, there was no standard size. Some beds are shorter than today’s standard, some beds are longer. Visitors are often surprised though when the guide takes a measuring tape to a “quote” short bed and then they find out it’s a lot longer than they thought. Today’s standard is 75 inches for a double bed.

I think it was in the 1980s, Colonial Williamsburg curators went around and measured all the antique beds in the exhibition buildings and found that all of them equaled or exceeded six foot three inches. Which is, that’s the standard today. Some are as long as 80 inches, which is today’s length of a king or queen bed. What curators think is that the high post, the fabric hangings, the canopy, the pillows, the ploofy mattress all combined to make the beds appear shorter to us than they really are.

Harmony: While we’re on the subject of furnishings in the bedroom, there is a story you bring up about there being a closet tax, so houses were built without closets to avoid the closet tax. Tell us about that.

Mary: That’s an often-repeated myth especially in the New England area, not just in the south, not just in Virginia. It’s another two-part myth really. First of all, many houses did have closets. They’re typically found on either side of a fireplace, more often in a bedroom or a dining room, and they were used just for general storage. Clothing wasn’t hung on hangers so they weren’t used the way we do them today.

People folded their clothing and stored them in furniture like chests or a clothes press or something. But today when people think of a closet, they think of a clothes closet. People didn’t have as much stuff back in back in the 18th century and even a well to do woman didn’t have that much clothing to store in a closet. The myth regarding the closet tax probably results from a misunderstanding about how closets were used and the fact they really weren’t located in every bedroom like they are today.

There was no closet tax, taxes varied widely from colony to colony but no researcher has ever shown up an example of a tax on closets in any of the 13 original colonies. So it’s a complete myth.

Harmony: One that I like involves the fashion of men who would tuck their hand into their vest you think of, I guess you always think of this as the pose of Napoleon where the man would tuck his hand into his vest to pose for a portrait. There is some mythology regarding the motivation for hiding your hand.

Mary: Right. The myth says that the reason the man’s hand was in his vest was to save money because the portrait painter would charge less if he didn’t have to paint the hand, the fingers which is a difficult thing to paint.There’s a variation of that called the arm and a leg myth. The expression that something costs an arm and a leg and that, the myth says that that came about because portrait painters charged more if they had to paint a subject’s arms or legs.

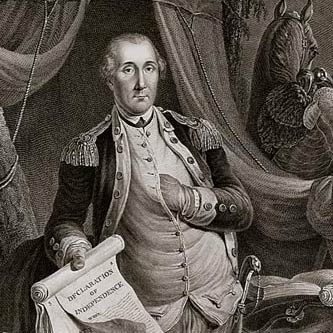

There is absolutely no historical verification for either of these stories. But standing with one hand tucked inside a vest or jacket was just a popular dignified pose for a gentleman of that era and we find it very commonly in portraits and in prints. It’s a little silly to think that people like King George III or the Emperor Napoleon or even George Washington were overly concerned about getting a discount from their portrait painters.

Harmony: What are some of the other myths you’ve run into that are fun to think about?

Mary: Well one of my favorites is the H and L hinges. This myth states that the colonists were so religious that they put H and L hinges on their doors to stand for Holy Lord. Well an H and L hinge is a stronger hinge than just a plain H hinge that you’re probably all used to seeing but. An extension of this story is that the Holy Lord hinges also protected the house from witches. This is also fairly absurd but these two tales are related to a third one about the paneled doors having been styled to resemble an open Bible, or a cross, or two H’s to stand for heaven and hell, whatever it is it’s all attributed to the colonists’ fervent religious beliefs.

Well first of all, not everyone had fervent religious beliefs and secondly, the H and L hinges are just stronger version of a symmetrical H hinge. They are particularly useful, in fact you’ve got to have them if you’re supporting the weight of a heavy wooden door. The key is the extra supporting arm that fastens to the door and this piece can be on top, but if it’s on top it looks like a H and a like a gamma, a Greek gamma, but on the bottom it looks like an L.

But either way it can be mounted on the other side as a mirror image of those. But it had absolutely no symbolic value at all. None of the myths that go along with doors about paneled doors or Bibles, or crosses have any documentation whatsoever.

Harmony: And some of these persist today in the modern hardware store.

Mary: The myth was mentioned in an online hardware site about buying the H and L hinges and our colonists who were so religious that they put their religious feelings on their doors.

Harmony: One that I’ve actually heard often and was surprised to learn is untrue was about the clay tobacco pipes and the long stems on the pipes.

Mary: Right. That came about for an obvious reason as excavations started here in the 1920s and 1930s the archaeologists found thousands and thousands of bits of white clay pipes, and you’ve probably seen the pictures, it’s a very long clay pipe with a small bowl and you. You needed the long stem because the clay bowl would heat up when the tobacco was burning and it would burn your lips if it were a shorter stem.

The myth started because people applied our own sense of the spread of germs and the spread of disease to what they were seeing in the ground, and it made sense to them that these bits of pipe must have been broken off when the pipe was shared with somebody else so that the disease and the germs wouldn’t. This myth has survived for decades.

But the problem is that the colonists didn’t know anything about germs or how disease was spread. So it never would have occurred to them that sharing the same pipe or the same cup was unsanitary. They shared things that we would not share today very freely.

Harmony: And so the reason for the broken pipe stems is what?

Mary: Is that they’re fragile. They are very easily broken if you’ve ever handled one carelessly, there are reproductions sold in the historic area, and they often break. So especially with the passage of time they would break in the ground.

Harmony: One of the most dramatic myths that you uncovered in your article was the flaming petticoat. The petticoat that bursts into flames and that it’s the leading cause of death for women.

Mary: That was one I had not heard until I heard it from other museums. I had not heard it here in Williamsburg, but apparently it’s quite common and also with reenactors where women work around, in long skirts, work around campfires. And this myth says that that death by petticoat was the leading cause of death for Colonial era women outside of childbirth.

Sometimes they say childbirth was the leading cause of death and sometimes they say it was petticoats catching fire. But historians studied the death records for all colonies and have determined that the leading cause of death for both men and women during the Colonial era was disease. Childbirth did take a shocking toll on women and an unfortunate few women probably did die when their clothing caught fire but the myth is a total exaggeration.

The curators speculate maybe just the horrifying nature of the whole accident makes some rare incidents stick in your mind and makes it more memorable and makes them seem more common.

Harmony: So you’ve had a lot of fun discovering these myths and tracking them down and it’s actually become more than just the article it started out with, it’s become a continuing project for you and you’ve actually started a blog where you’re collecting and discussing myths.

Mary: I have and that other museum professionals from other museums will contribute what they’ve heard and maybe we can debunk a few more.

Harmony: Where can people find your blog if they’d like to weigh in on the discussion?

Mary: www.historymyths.wordpress.com

Harmony: We hope you’ll find Mary’s blog and weigh in with any myths you might have heard or any insights into some of the ones she’s discussed. Mary thanks so much for being here today.

Mary: You’re welcome.