What’s lost is found, safe in a place it never left. Scott Stephenson describes a rediscovery.

Podcast (audio): Download (3.4MB)

Subscribe: RSS

Transcript

Harmony Hunter: Hi, welcome to the podcast. I’m Harmony Hunter, filling in this week for Lloyd Dobyns.

My guest today is Dr. Scott Stephenson, who is director of collections and interpretation for the American Revolution Center at Valley Forge. Scott is joining us today to talk about 18th century woven beadwork from the American Southeast. And Scott, I notice when we’re describing – when you’re describing – this beadwork, you’ve used the phrase “hidden in plain sight” to describe it. Why?

Scott Stephenson: Well, the story began on the back of a polar bear in Scotland, to be completely honest. I was doing research in Scotland, almost 20 years ago now. I was interested in the Seven Years War, the French and Indian War, as it’s called, and was looking for letters that had been written from North America back home, sort of describing life in America and the conduct of the wars. Lots of Scots, of course, served in the British Army, came to North America but kept in touch with their families. So it’s a very rich source of description.

I just happened to go to this one house, a private home in Scotland, and was looking at the papers. Because I’m also very interested in material culture, just asked, “Do have any old things from America here?” So they brought me back into this sort of closet area, and there was literally an old stuffed polar bear on wheels that you could sort of wheel around, and then right behind it was a cabinet with some American Indian items, including a couple of these woven pieces – a garter, and a broad, five-foot long very dramatic sash, or belt that had been woven with thousands of these glass beads.

Harmony: What did you think when that cupboard was opened?

Scott: You always get excited when you see sort of new stuff that hasn’t been published before that’s new. Scotland, maybe because there’s low temperature and low light, the preservation of these items tends to be remarkable. They were sort of collected as curios in the 18th century, and they have not suffered.

You know, we have a lot of heat and humidity and insects here, particularly in the South and in America, but in the North as well. The things just don’t survive in as good a condition. So some of these pieces just look like they had been made yesterday. It was really remarkable.

What was, the sort of “aha” moment was, that same day, seeing these items and realizing, ‘I just saw a reference to these in a letter written in the 1760s by an officer in the British Royal Navy, talking about sending a sash and a pair of garters home to Scotland to be part of this cabinet of curiosities.” So that started a whole, we could be here for four hours as I tell you the sort of all the serendipity and happy accidents along the way, but all of a sudden this sort of constellation of objects, that either through more research yielded direct evidence, or sort of through association and circumstantial evidence, all of the sudden, you could sort of draw a circle around this group of items that all appeared to have been made before 1800 in the Southeast from the Pensacola, St. Augustine area up into Cherokee country and over to the Mississippi. So it was very, very exciting.

Harmony: So this is why it was hidden in plain sight. You just needed to assemble all of those clues, and look at them through one lens.

Scott: Sure. You know, so often, the objects -- the antiques, or the artifacts -- they become separated. You know the first great separation and perhaps the most tragic is their separation from the native communities and cultures that produced them. The second separation is that they are often separated from the context that they have been cared for all these years, which often includes letters and information about where and when they were collected.

So, what would typically happen is these things would, maybe there’s a death in the family and the estate is settled. Objects like that will go off to an auction house somewhere and they’re sold as beautiful items of American Indian production, and they fetch very high value. They fetch very high prices. But there, sitting sort of moldering away on old slips of paper in the closet, is the actual documentation that tells you what this is, or who collected it, or the clues to help plug these things together. This happens sort of several times at key points in what became this project for me.

Sort of encountering these collections, still in the hands of the descendants of the original collectors, with the documentation that allows you to knit it together. So then it made me of course realize that how much do we really know about any of this stuff? So it’s great, fun, detective work.

Harmony: You’ve used the term “material culture” a few times. What does that mean?

Scott: Well, it is really just about any item of dress or the type of domestic wares that you use in your everyday life. It’s the expression of a particular culture through the material world – whether it’s clothing, whether it’s things that you cook in, or the architecture that surrounds you.

Harmony: So the physical surroundings of daily life. What are the objects that you’ve found?

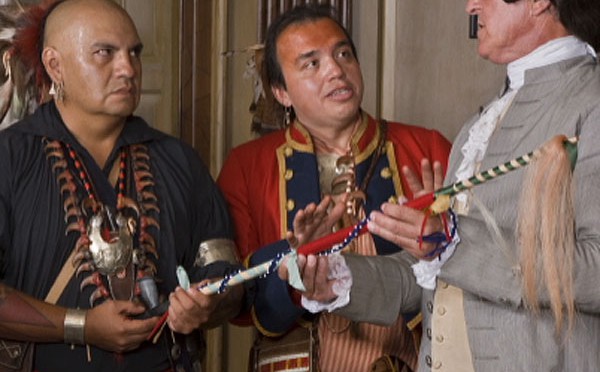

Scott: They’re a combination of garters, which are worn around the knee, that are used in most cultures to keep socks up, or other garments in place. There are sashes that might be worn around the waist or over the shoulder, also small pouches. What distinguishes these items is that they’re constructed – their appearance is almost that it’s almost solid glass beads. They’re generally small colored glass beads: white, black, a deep red garnet color very common.

They’re woven so they become a kind of textile, but they’re not woven on a loom, it’s actually handwork. Various techniques of handweaving, of using often wool or fibers that are produced from native plants or things that are received through trade with Europeans, and glass beads. So quite a few items received in trade with Europeans but then are combined together in a very unique native expression, artistic expression. They’re really quite beautiful.

Harmony: Are we talking about utilitarian items, or ceremonial?

Scott: Well it’s difficult. We have to be careful in separating the secular and the spiritual, both for European cultures in the 18th century – I think we live in an era in which the separation of church and state is sort of taken for granted. So even for Europeans in the period, that may not have been a real distinction for many people. I think it’s fair to say, particularly in native America, what’s considered sort of utilitarian and ceremonial or spiritual may not be a real distinction.

A lot of these items have really lost their cultural context, because they, because like all cultures, native culture was not frozen in time. People changed, their material culture changed under the stresses of the colonial experience for native people and forced migration and amalgamation of different groups. You had new influences coming in, new types of items and clothing, fashion.

So one of the reasons it’s been difficult to recognize these pieces is because they, by and large, for most groups, stopped being made in the early 19th century in favor of other types of decorative arts. Those became the sort of recognized tribal styles that you would often see. If you went to Oklahoma today and many of the distinct tribal styles of Southeastern Indian peoples are not necessarily what you would have seen in 1750. You might have seen them in 1850.

Harmony: Thinking about that cultural flux, what do the items that you found, what do they tell you?

Scott: One of the things that it really got me thinking about is the connections between native people. If you think about waterways not as barriers like we do today, that have to be bridged, but as highways that connect people together, of course you can get on a river in Minnesota and go to Louisiana. So, the superficial resemblance between these things, both in terms of the technique and the appearance, speaks to the great connections between native people.

They were not living in just isolation waiting to be encountered by Europeans. There was this sort of rich, interconnected world Europeans came into, and that really speaks to great connections and great cultural dynamism in adapting new materials, making new items, interpreting old. Many of these have old designs that go back to pre-Columbian pottery and other art, so there’s traditional aspects and innovative aspects as well.

Harmony: What makes this beadwork so rare?

Scott: I think it’s a combination of things. These items were often collected in the 18th century. This was the era before sort of anthropology, before you are collecting items of human culture for the purpose of documenting the lives and cultures of peoples around the world. They tend to be collected as curios, they were often called savage curiosities. There’s not a lot of concern about who specifically, what specific group made this. What community did this item come from? It’s just, it is an 18th century tourist item, in a sense.

I think you also have climatic issues that just the survival rate of things in general, whether it’s euro-American or American Indian in the South tend to not be as good as in colder climates. That would be my guess, that it’s a combination of those things.

But again, going back to the title, “Hidden in Plain Sight,” I do believe that there are probably lots of other items that are sort of mis-catalogued at the moment. We may, in fact, have a much larger body of material culture for the native people of southeastern North America than we think we do.

Harmony: Thanks for being with us today.

Scott: Thank you.