Revolutionary-era cannon are artifacts of war technology’s evolution. Director of Historic Trades Jay Gaynor and Master Blacksmith Ken Schwarz describe the process of recreating a light infantry three-pounder.

Podcast (audio): Download (3.2MB)

Subscribe: RSS

Transcript

Lloyd Dobyns: Hi. Welcome to Colonial Williamsburg: Past & Present on history.org. This is “Behind the Scenes” where you meet the people who work here. That’s my job. I’m Lloyd Dobyns and mostly I ask questions.

Cannons dot battlefields across the United States, where their presence suggests the violence of combat. But their solid heft is also evidence of the hands of the men who made them. Founders, blacksmiths, wheelwrights, gunsmiths and brickmakers are only a few of the tradesmen who collaborated to produce a weapon familiar to every regiment.

Director of Historic Trades Jay Gaynor and Master Blacksmith Ken Schwarz are here now to talk about their efforts to recreate an 18th-century cannon.

Jay Gaynor: This whole project is possible because of the generosity of the Fredrickson Foundation. They’ve given us the funds that we’ve needed, both to get the materials for the project, to do some of the research for the project, and also document it. So we’re very grateful to them for that.

Lloyd: Who needs to do what, when, to make this a usable cannon?

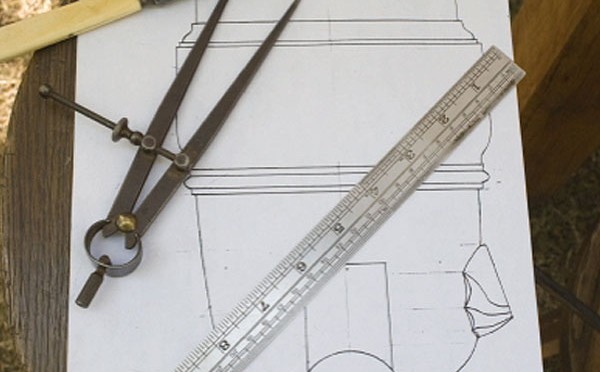

Ken Schwarz: Well, obviously, you have to have the barrel made. The founders have a good start on that. They’re using 18th-century descriptions and illustrations from the time period that show the process of creating a model of the original cannon, then using that model to create a mold for what we’re going to produce, then taking out the model and putting the mold next to the furnace.

The furnace will be used to liquefy the bronze, which will then be poured into the mold and then the mold being a clay, baked clay mold, that will just be broken up afterwards, leaving the shape of the cannon. Then there will be finishing work that entailed cutting of excess material, turning the barrel on a lathe in order to finish the outside and polish the outside. Boring out the hole, the bore of the gun.

So that’s one process. The other process involves primarily the wheelwrights and the blacksmiths creating the wood components of the carriage and then the blacksmiths reinforcing the wooden components with iron bands.

Lloyd: You said, “boring out the barrel,” now I know from having watched, when you’re going to make a round candlestick, you pour two halves, and it’s empty in the middle, and you join them together, finish it off, and there’s the candlestick with a hole in the middle and you don’t have to bore anything.

Ken: Right. When you’re producing a candlestick that way, economy of material use is very important. That’s why you cast the candlestick in two halves, because it leaves the center part of the candlestick hollow. In other words, you can make a full-sized candlestick using less brass, and that’s a cost savings that you pass on to the customer. The candlestick doesn’t require a great deal of strength.

In the case of the gun barrel though, it will require a great deal of strength. You have to make sure that the casting is flawless, so that it doesn’t fail in use. That’s why these are cast solid and then bored out.

Jay: This is a change that takes place about this time, in the mid-18th century again. Up to that point, they had cast the cannon using a core, so that when it was molded, there actually was a hole in the middle of it when it was pulled out of the mold. In doing so, the reason they did that was not to save brass, but because they didn’t have a really effective means of boring that deep hole into the bronze.

By the time we’re talking about, in the 1770s, the practice had shifted to a whole new technology where, instead of lowering the gun barrel onto a turning drill bit, everything was mounted horizontally and actually they turned the cannon barrel and fed it into a stationary bit.

It’s hard to conceptualize theoretically, but that resulted in there being a straight, concentric hole through the cannon, whereas, otherwise, you weren’t assured of that. By being able to cast them solid, you were much more likely to get a good, solid casting without any porosity or honeycombing or whatever in it.

Lloyd: Ok, you now have this solid 41-inch barrel, but it’s not a cannon. There’s nothing for the three-pound shell to come out of. How do you make certain that the bore is straight?

Jay: Exactly. That was one of the big problems with rotating the drill bit into a stationary barrel. But, when you’re rotating the barrel into the bit, the whole physics of that tends to center the bit in the core, or in the casting. So you end up with a hole that’s concentric with the axis of the casting.

It may vary a little bit in diameter, because that’s where the compensation takes place. You’ve got that essentially straight hole through the middle of the gun, and then once that’s there, you can go in with other bits and make sure that it’s all in an even diameter all the way through and that it’s polished.

Lloyd: Do you know how to do that the way they did it?

Jay: We have a decent intellectual understanding of it, but it requires incredible equipment to do it. It’s tons of equipment mounted on stone, because you have to eliminate vibration and so forth. The process is not really too much different from the way a typical machine shop today with modern equipment does any sort of deep hole drilling.

This is the one aspect of this project that we’re going to do in a modern way. Once we get the casting, we’re going to put it on a lathe in our machine shop here and actually drill it using the same theoretical technology as the 18th century, but modern equipment.

Lloyd: Now, I asked you how long it was; I did not ask you how long the bore is. You’ve got a 41-inch cannon – how much of that is actually cannon, if you will?

Jay: I think it’s about three feet.

Ken: When we cast one of those also, the breech end of the gun is made up as a separate mold. So the length of the barrel is created as a mold that’s hollow all the way through, and then there’s a solid pattern for the cascable, the breech end.

That has to be set in the casting pit first, and then the hollow mold is lowered down on top of that and has to be a good fit, it has to be level and square. So it’ll be bored out to close to where the cascable joins it, and the touchhole would be drilled from there also.

Lloyd: I have read part of the material, and they say this is a three-pounder. What does three pounds refer to?

Jay: Three pounds refers to the weight of the ball that it shoots.

Lloyd: Ok, that was our guess.

Jay: Right, and that’s the way 18th-century artillery is generally classified, is by the weight of the projectile, the solid shot.

Lloyd: Ok, so to give us an idea, was there anything smaller than a three-pounder?

Jay: There were one-pounders, but three pound is basically about as light as field artillery pieces get. The reason for a piece that small, compared to 12 or 24 or 48- pounders, was its mobility, the ability to be able to get it around in a tactical situation.

Lloyd: Was it carried around by men, or horses, or mules, or whoever you could get to pull the thing?

Ken: This particular cannon is made so that it can be moved either way. It’s set up so it can be drawn by horses when you’re going a great distance, but the reference to it being a light three-pounder is the fact that it can be fitted with handles and the whole thing lifted by soldiers and maneuvered by carrying it on their shoulders.

Lloyd: I bet they would have picked horses.

Jay: I think that would be the preference. Actually, it sort of represents a new approach to the use of artillery that was being developed in the mid-18th century. Up to that point, cannons were big and heavy and awkward.What you tended to do is, you put them in position and that was almost a static position, at least for the time being.

The development of these really light guns meant that you could maneuver them out in front of the infantry, you could maneuver them with the infantry themselves, and they were designed to be infantry support weapons, and had that tactical mobility and flexibility that that kind of task demanded.

Lloyd: Did both sides have three-pounders?

Jay: We had three-pounders after Saratoga, because the first 20 of the type of barrel pattern that we’re going to cast, were supplied to General Burgoyne for his march out of Washington. With the surrender at Saratoga, I believe we acquired 20 of them.

Lloyd: Well, that’s as good a way as any.

Jay: They ended up exchanging hands. There’s all kinds of tales, if you read the literature that’s put together on it. You know, one side would have them in a particular battle, they unfortunately – or fortunately – lost, the other side acquired them, they used them for a while, then they were lost again, so they traded hands off and on all throughout the whole war.

Lloyd: What made you decide to build one?

Jay: It actually was a fairly unusual weapon. Three-pounders had been in place before this time, but they were much larger, bigger guns. The ones that we’re reproducing were actually developed for use in North America. Almost all of them were produced in 1775, 1776, and almost all of them came over here. Their production really stopped after that. It is kind of an anomaly in the whole family of cannon.

Lloyd: How long is it, and how much does it weigh?

Jay: The barrel’s about 41 or 42 inches long, so, you know, not terribly long. The barrel weighs a little bit over 200 pounds, so it’s very manageable by a couple of guys. The wheel diameter is about three feet, I think. Maybe a little bit more than that.

Lloyd: So it is a thoroughly manageable gun.

Jay: You aim the whole thing, the whole carriage. But yeah, one guy can pick up the back end of it and roughly point it where it needs to go.

Lloyd: You stuff powder into the barrel, then you load your shot. Is there anything else that needs doing, or is that it?

Ken: Then, so, when you load that way, you have the powder – and that’s usually wrapped in often a cloth package – and then the projectile is seeded securely on top of that. The touchhole, or the vent that I referred to, will be filled with gunpowder.

So you reach down in the vent with a little iron pin, pierce the wrapping of the powder, and then fill the vent with loose gunpowder. There’s usually a little flat area on top of the vent that you fill with powder. When that’s touched off with a burning slow match, the gunpowder burns down through the vent. When it reaches the powder charge, that’s when the explosion occurs.

Lloyd: And the projectile leaves the cannon, instead of the cannon leaving the projectile.

Jay: Right. Although, the cannon does kick. Even this little cannon with a relatively light ball will recoil significantly. You don’t want to be right behind it when it goes off.

Lloyd: I would presume the artillerymen would have learned that probably the hard way.

Jay: That’s what the whole drill is all about, is how to keep those guys not only efficient and slick in their operations, but safe. What’s also unusual about the gun itself – is, it was really meant to be a self-contained unit. Once you had the gun, and all of its fittings, and the limber, you had, that included ammunition ready to go, because it was meant to be deployed quickly and into action quickly, so in some cases it was the components Ken just talked about were actually assembled.

You had iron shot, or the case, which is like a big shotgun shell, sitting on a wooden base. Then this powder bag is tied to that. So literally, it was a one-piece bit of ammunition, which speeded up fire tremendously. One of the neat things about the gun, in addition to all the things that Ken talked about, and it’s manageable size and as a manageable project, is, we have a huge amount of information about it, per se.

So, we know the type of ammunition that was packed with it, where it was packed, how much it weighed. It was supplied with block and tackle to move it around. It was supplied with man harness to drag it around. It was supplied with an oversized musket for sort of, added defensive capability.

We know how all of it was stowed on the gun, we know the drill that was used to load and fire the thing. We’ve got this huge amount of information. Probably much more so than just about anything else I can think of that is that complex, in terms of all the components of the overall piece.

Lloyd: Follow the progress of the cannon’s construction on the blog at history.org/cannon. Listen to next week’s program for a continuation of our discussion with Jay Gaynor and Ken Schwarz.