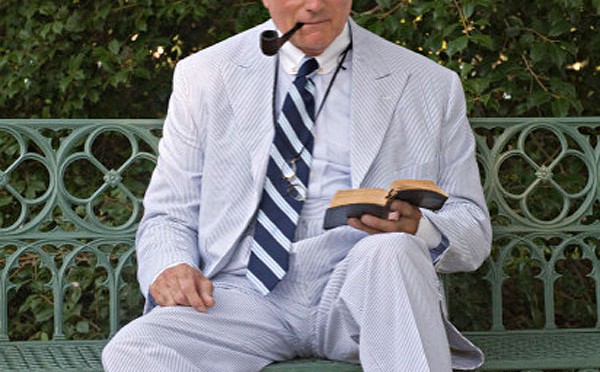

Inspiration intersects with means in a partnership that resurrects a city. Character interpreter Ed Way portrays W.A.R. Goodwin at Colonial Williamsburg.

Podcast (audio): Download (2.8MB)

Subscribe: RSS

Transcript

Lloyd Dobyns: Hi. Welcome to Colonial Williamsburg: Past & Present on history.org. This is “Behind the Scenes” where you meet the people who work here. That’s my job. I’m Lloyd Dobyns and mostly I ask questions.

In 1926, Williamsburg was a boomtown gone bust. Ramshackle houses and slipshod stores shaded streets where traffic rarely stirred. If not for the efforts of one Reverend Goodwin, the town might have been lost to history. Character Interpreter Ed Way portrays Goodwin at Colonial Williamsburg.

I think at Colonial Williamsburg, you're one of the few characters who dresses for 20th century. If you don't dress him for the 18th century, which clearly would not fit, how do you dress for the period of the, what I would call the first third of the 20th century?

Ed Way: Well, I have had a costume made for me by the department for which I work, done by Nathan's of Richmond, a tailor who specializes in 1930s and '40s suits. My cotton seersucker is made from a 1930's pattern. It differs from modern clothes in that it has a higher waist, has suspenders instead of a belt, it has a wide edge or rim cuff on the pants, and sits a little higher off the shoe. Also some differences in the lapels and general design of the coat. It suits me very well.

Lloyd: Do you like it?

Ed: Love it. It's cool, and good for interpreting out of doors, which is what I'm presently doing. It fits me like a glove.

Lloyd: How do you interpret W.A.R. Goodwin?

Ed: He is not easy to do. He was an extraordinary personality. So much of his success as a fundraiser and a preservationist, a restorer of ancient structures had to do with this fantastic personality. He was an ultimate extrovert. Loved people, drew energy and strength from interacting with people. He was charming to the point of being charismatic. Now, I'm portraying him in 1937, at which time he was 68 years old, already in some failing health due to heart failure.

So that gives me a little strength for portraying Goodwin in a somewhat reserved form, as to the man he was earlier in life. But he was an extraordinary man, he was broad-shouldered and husky, enjoyed wonderful health all his life, worked morning, noon, and well into the night. Survived on very little sleep, and never seemed to require a whole lot of rest in any form.

Lloyd: He convinced John D. Rockefeller to finance the restoration of Colonial Williamsburg. Prior to that, he tried to interest the Ford family, and wrote what I have always believed was the least public-relations conscious letter I have ever read to Ford saying, "Since your cars are ruining this town, I thought you might like to restore it."

Ed: I can't imagine what he was thinking with that letter. He had a tendency to be candid about some things. He did correspond for a period of months with Edsall Ford, the son of Henry Ford, in the hope of drawing in the founder of the Ford empire. But he never did so.

He corresponded some with Whitneys and Morgans, and had not been able to find the right man. He needed somebody of enormous wealth who shared his fascination with colonial America, who shared his enormous sense of American heritage, and who was wanting to have an opportunity to enshrine an extraordinary moment in history.

It wouldn't be easy to find someone like this, but the man turned out to be John D. Rockefeller Jr. It's sort of like there was a splendid coincidence. Goodwin had the vision, and desperately wanted a benefactor. Rockefeller, fascinated with history, had the fortune and was waiting for an opportunity to prepare an extraordinary gift for future generations of the American people. Now, people often think that Goodwin gave Rockefeller a hard sell.

Goodwin says, "No, I never did much more than talk enthusiastically about my dream and vision." He said it didn't take much to draw Rockefeller in because he was ready. He had the desire for that kind of involvement. Now, they took three walks through the restored area in 1926-'27. Rockefeller says at one point, "Some people get taken for a ride, I got taken for a walk that cost me 68 million," implying that perhaps he was given a hard sell.

Actually that was not the case. The men were part of the same movement: colonial revivalists who loved to look back in the midst of a period of enormous industrial capitalization and to admire and want to create certain aspects of the colonial past – architecture, furniture, art, attitudes, and values. That's what they shared.

Lloyd: I have been told that Rockefeller was interested, to a degree, because it was the only place he had seen or knew of where he could restore a whole village. It wasn't just three buildings and a street, it was the thing, whole thing.

Ed: Absolutely.

Lloyd: Was that part of Goodwin's idea?

Ed: It was, and it was a critical aspect of the presentation to Mr. Rockefeller. Mr. Rockefeller said to Dr. Goodwin, "What is it about Williamsburg that is so unique that I would wish to enter into this enormous restoration project?" And Dr. Goodwin said, "There are indeed many historical sites all over the east coast: Boston and Philadelphia – but the historical sites, the structures, are spread out. How would you ever draw them together into a community when you're talking about such size? But Williamsburg is a little jewel of 300 acres. One-half mile square, and all the history takes place within these convenient boundaries. It's a jewel just waiting to be restored."

I think that was a significant part of Goodwin's presentation that convinced Mr. Rockefeller to undertake what really, nobody had done before: to restore an entire community.

Lloyd: It's really quite clever of Dr. Goodwin to think of that. To say, this is a village that you can rebuild. You can make this a piece of history that people can come and look at and understand. It's all in one place. I wonder where he got that idea?

Ed: Well, he got it from his own study of history. He had been a scholar of history and philosophy and theology from the time he was a teenager. He also was a man very skilled at saying the right things in terms of fundraising. His instincts were good, he knew what to say, and when to say it.

So he just had this talent. It would have served him well in so many fields that could have made him a rich man, but he always, regularly, showed very little interest in money, and for a number of years, refused to allow Mr. Rockefeller to compensate him in any way for his early involvement in the restoration.

Lloyd: Did Dr. Goodwin have a favorite building? Did he prefer one over any of the others?

Ed: He had a favorite spot in Williamsburg, and that was Bassett Hall, the old 585-acre farm on the periphery of the restored area. As a young man in 1903, as a young rector of Bruton Parish, he had been drawn to that site and loved to sit beneath a 300 or 400 year old white oak tree located at the edge of cleared land at the south part and sit under there and do what he called "commune with the ghosts of the past."

He communed with the ghosts, he liked to say, of Jefferson and George Washington, Patrick Henry, George Mason, and James Madison. It was during those times when he would sit under that tree that he first conceived the idea of a restored Williamsburg. So that site, and that old tree, have particular significance to the story of Colonial Williamsburg.

Lloyd: I had never heard that. That was his favorite place?

Ed: Favorite place. And he took Mr. Rockefeller three times to that site, and twice Mrs. Rockefeller was with them, once three of the sons were with them. So it was a special place to the Rockefellers, as well. And ultimately, the Rockefellers purchased Bassett Hall as their own home in Williamsburg, and for 12 years came regularly to Bassett Hall, fall and spring to spend time in this project that had come to occupy a special place in their hearts. They really loved Williamsburg.

Lloyd: WA.R. Goodwin was committed to the restoration of Colonial Williamsburg. Talked John D. Rockefeller Jr. into it, and he did not do it for the money so far as anyone can tell. What was his pride? Did he ever say anything about it?

Ed: I think in his latter years, it was a very satisfying thing. It was taking shape very nicely by 1934. So between '34 and Goodwin's death in '39, as his health was failing, and he had a little more free time, he had opportunity to gaze over this beautifully emerging restored city, and look with some pride at what he had accomplished and was accomplishing with every passing month.

He was a man humble by nature, but I think, like all of us, he couldn't help but to enjoy it when people refer to him as an institution – the man who grasped the vision, the man without whom there would have been no Colonial Williamsburg. It gave him an opportunity to talk with people in his latter years, to reminisce, and to do what we older men love to do: talk about the past.