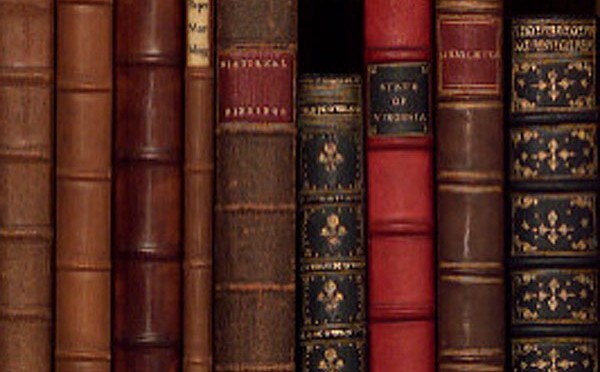

When a single book cost half a year’s wages, tomes were rare treasures. Bruce Plumley describes the bookbinding trade.

Podcast (audio): Download (2.5MB)

Subscribe: RSS

Transcript

Lloyd Dobyns: Hi! Welcome to Colonial Williamsburg: Past & Present on history.org. This is "Behind the Scenes" where you meet the people who work here. That's my job. I'm Lloyd Dobyns, and mostly I ask questions.

Joining me today is Bruce Plumley, a man who can tell a great deal about a book by its cover. At Colonial Williamsburg, he's the master bookbinder, and works with books.

Bruce Plumley: That's correct.

Lloyd: How long have you been doing that?

Bruce: Come the 14th of January next year, 2008, 51 years.

Lloyd: What attracted you to it?

Bruce: My father was a bookbinder before me. So I'm second generation. My mother was also a bookbinder, believe it or not.

Lloyd: Oh really? So that's the whole family.

Bruce: Pretty much, yes.

Lloyd: Did you find it as satisfying as you thought it would be?

Bruce: I found it more satisfying than I thought it was going to be, yes.

Lloyd: Is that, watching your mother and father work, and then …

Bruce: No, because I apprenticed under a different master. I didn't apprentice under my father. Eric Burdette, who was awarded the MBE [The Most Excellent Order of the British Empire] by the queen for his dedication to bookbinding. So, I served under a very famous person in the bookbinding world – not famous to the majority of people.

Lloyd: So you apprenticed in London?

Bruce: No, in South Hampton, in southern England.

Lloyd: When did you come here?

Bruce: I came here in '85. 1985, not 1785.

Lloyd: (Laughs.) That would have been more than 51 years, wouldn't it? What is the hardest part to bookbinding?

Bruce: I guess the designing of it, and also the gold tooling.

Lloyd: Is it tough to work with? It must be.

Bruce: It's tough to work with, but also to get it to adhere to the leather, because it's only 1/250,000 of an inch thick. You have to control your breathing when you're working with it. You can't have any draft whatsoever in the room. If somebody were to open the door when you were working on that book, the gold would just flutter up in the air. You have to try and retrieve it without touching your fingers, because it will stick to your fingers, and then it's ruined.

Lloyd: That would certainly make you hate the person who opened the door.

Bruce: Yes. Or walked past you, you know. Just the movement of the air of somebody walking behind you would be enough to stir up the air.

Lloyd: What are the steps in the process?

Bruce: Well, as a minimum, there are 28 different stages to the book's production. The very first step is to fold paper into multiples of four pages. You know, folded in multiple sections, gathered and collated, then pressed, and then sewn.

Of course, we not only use sewing, but we also glue the book as well with an animal-hide glue. When you've got a combination of both sewing and gluing, the book should last you a long time – two to three hundred years.

Lloyd: Well, that's fairly long.

Bruce: Yes, and the paper will last even longer than that, because the paper is 100 percent rag fiber. Rag fiber paper will last indefinitely. There's no acidity in it, so therefore it doesn't go yellow or brown, or crumble.

Lloyd: For years and years and years, I have been told that eventually most of the books in my library will turn brown, because the paper is not meant to last but "x" number of years.

Bruce: That's right. If it's 150, or less than 150 years old or thereabouts, then you've got wood pulp paper. That's when books will start to deteriorate. Anything that's older than 150 years is more than likely going to be rag fiber paper. Therefore, they will last indefinitely. You can have it rebound every 300 years.

Lloyd: You gave me the first step. What's the last step?

Bruce: Well the last step is to do the decoration on the book, really. If you're going to do it in blind tooling, which is the decoration which is done just by impressing in the leather with a heated tool and moistened leather, that gives you a slightly darker impression where the tool has touched. That's what we call blind tooling. But of course, you can do the same thing in gold. That's the most skilled part of the bookbinding trade, really.

You see, we don't regard books as being treasures anymore. We can buy them for next to nothing now. Back in the 18th century, and centuries before that, they were real treasures. It was really something to have a book in those days. Most families probably only owned a Bible. Ordinary families, probably the only book they owned. Depends on their interests of course. If you're willing to do without a number of things, then you might be able to have a few more. In general, the family Bible is handed down through the generations, because of its sheer cost in the first place.

Lloyd: What would a family Bible cost?

Bruce: Yes, but usually a family – because it may be the only book they owned – they've had to save up for a long, long period of time, maybe years, before they could afford to have a really nice Bible. Could cost them an absolute fortune. It could cost £6. But you could also buy it for five schillings, in cheap form, then have your favorite bookbinder bind it into something that was unique just for them. But £6 for the ordinary person who was unskilled, white, only earns about £12 to £15 a year, you've got close on half a year's earnings invested in that, just that one book. But the majority of books that we produced here in colonial Williamsburg, 90 percent, or close to 90 percent, were actually blank. They were ledgers and account books for the business people – plantation owners, merchants, doctors, lawyers, seats of government.

Lloyd: How much did, has anyone ever figured out how much Jefferson had invested in books? He started the Library of Congress because he had so many books.

Bruce: That's true. To give you some idea, there are some records a colleague was telling me about. There are some records still in Richmond. An insurance company that insured Monticello, his home, the mansion, for $5,000. He insured his library separately, for $75,000. Fifteen times more than what his mansion was insured for. Could you imagine having that much invested in books?

Of course, he didn't get $75,000 for them. He only got $25,000 for them because he was not only a book collector, but he read virtually every book he owned. He was so enthusiastic, literally about everything he did, he wrote his comments in the margin as soon as he finished reading the page. He'd turn over the next page, read that, and write his comments in the next margin. So he defaced virtually every book he owned. So he only got $25,000 for them.

Lloyd: You've brought a book with you that, I didn't pick it up. It's got a three-dimensional face on the front cover. How do you do that?

Bruce: Well, I had to use a totally different technique than normal bookbinding to be able to do that. Because you can see the face actually stretches through the leather. It looks like somebody's actually been bound into the book. It's been done in sheepskin, and sheepskin is a very flexible skin. It has a lot of stretching qualities, so therefore I was able to stretch it over a face. As you can see by the title, it says, "Let's Face It."

Lloyd: What's the book that you've worked on, anywhere, that you were proudest of when you finished with it?

Bruce: I guess when I get commissioned to do books for royal families. The queen of England, the Queen Mother, and I also did the royal guest book for Prince Charles and Princess Diana's wedding in 1981. So that's kind of like cream on the cake.

There was one book in particular that's actually on permanent exhibition in Vancouver. It was called "Flowers and Heraldry." I did a binding in a sage-colored leather, with a gauntlet, a metal gauntlet holding flowers. "Flowers and Heraldry" across the front board, and that was done in silver kid with the knuckles of the gauntlet done in inlaid gold kid.

It really was, when you looked at the book, it really hit you. I think that's why it got to be on permanent exhibition in Vancouver. But that was a collector that commissioned me to actually do that book. After I finished the book, I kept it for two months, and didn't tell the owner of the book that I finished it, because I had trouble in letting it go.

Lloyd: There's a difficulty if you're trying to make a living. Eventually, you have to sell it, or get your commission. You said things for the royal family. Is that as pleasant as I imagine it would be?

Bruce: It is. Obviously, as I said, it's really the cream on the cake when you get commissioned to do something really, really special. It can take a long time. The queen said, when I did the royal guestbook for Prince Charles and Princess Diana's wedding in 1981, "We're going to give you a free hand, we'll accept whatever you do. But please don't make it too ostentatious."

Lloyd: How could you not make it ostentatious?

Bruce: Exactly, yes. That's limiting you. In other words, anyway, she didn't want gold. She didn't want gold on it. So I made silver frames, sterling silver, and silver clasps inlaid in it with Moroccan goatskin as well. And then, the boards on the inside – the boards were solid wood, English oak, quarter sawn, so it had nice flowering on the inside, and that was French polished with suede flyleaves facing the French polishing. Then, leather on the outside with the silver frames and clasps.

That's what I was trained to do, really, as a bookbinder, as an apprentice with Eric Burdette. He was, as I said, a well-known bookbinder and I'm very proud to say that I was one of his apprentices.