An early plantation slumbers beneath Williamsburg’s streets and foundations.

Podcast (audio): Download (2.8MB)

Subscribe: RSS

Transcript

Lloyd Dobyns: Hi! Welcome to Colonial Williamsburg: Past & Present on history.org. This is "Behind the Scenes" where you meet the people who work here. That's my job. I'm Lloyd Dobyns, and mostly I ask questions.

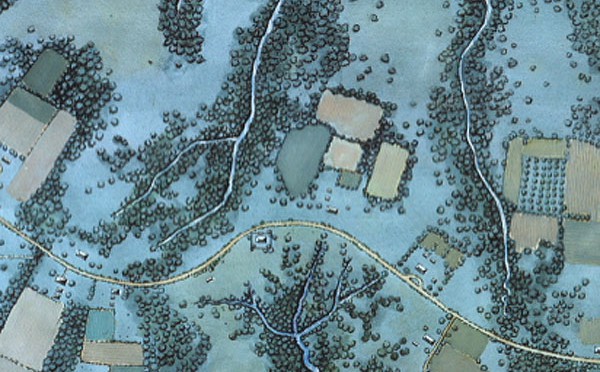

Concealed beneath the geometric grid of Williamsburg's streets is another town, the town that existed before Williamsburg became Virginia's capitol. Traces of this early outpost are few, but a fresh approach to studying the artifacts sheds new light on Middle Plantation.

Kelly Ladd-Kostro, who is the associate curator of archaeological collections, is with me today to talk about the ways that Colonial Williamsburg's archaeologists are piecing together the mystery of this phantom plantation.

The first question, I guess, is was it a phantom plantation, or was it a town?

Kelly Ladd-Kostro: I guess I would say it was neither, to be honest. It was a large place, actually. It came into existence around 1632 as part of 300,000 acres that were enclosed by a palisade. This palisade, the idea behind it was to help protect the people from what they viewed as a potential source of problems through the indigenous peoples in the area. It was really Virginia's first attempt at interior settlement. It wasn't until the 1640s, '50s, and '60s that you really start seeing large numbers of people coming into the area. You have some big hitters, like John Page, who was a lawyer and a planter. You have Thomas Ludwell, who is the secretary of the colony. There were some rather big minds and individuals with a large amount of money coming into the area.

Lloyd: You've obviously done enough research to know who was here. How big a place was it? Did you have a general store, or a tavern?

Kelly: It did. It's interesting you should ask that. We know for a fact that there were taverns and other establishments in the area. Bruton Parish came into being around that time as well, later in the 17th century. The college comes into existence in the late 17th century. We have maps that talk about road systems going from Jamestown into Middle Plantation. There was definitely a great deal of activity taking place here. All that would make you think then, that there should be a large number of archaeological sites somewhere out there, because there was so much activity taking place.

Lloyd: Obviously there aren't, or you wouldn't have brought it up like that.

Kelly: Well, yeah. That's a very good point. We, over the years of digging – now for over 70 years – have come across bits and pieces of Middle Plantation.

Lloyd: You've brought a box. I hope it is of bits and pieces.

Kelly: I did. It is of bits and pieces, but we have archaeological fragments that are bits and pieces. We also have architectural signatures in the ground. By that I mean, in the 18th century when we were digging, we would oftentimes have found what people commonly think of in the Williamsburg area as being 18th-century buildings, so, brick structures. In the 17th century, you were more likely to come across what we describe as post in ground structures. For some of the larger plantations, such as John Page and Ludwell and others, you did have brick as well, which is definitely a sign of wealth. There is some evidence that way in the ground archaeologically, from an architectural standpoint.

But post in ground structures are very, very hard to find as a signature in the ground. Especially if you consider that you had a capitol that came here and planted itself in 1699, on top of this area that had been known as Middle Plantation. Lots of construction, lots of activities for about 80 years. Then you have the 19th and 20th centuries, kind of quiet little southern hamlet here of Williamsburg as a little city, as a little town. In the 1930s, you had the restoration start, which continues on today. That's a lot of impact to have on an area. An archaeological area, if you want to think of it that way, to try to find those signatures, to try to find those sites.

Lloyd: So in fairly close time proximity, you have two distinct types of areas, one on top of the other.

Kelly: They're sandwiched. They're sandwiched on top of each other. You have Middle Plantation, then you have the capitol after 1699, then you have the town here in the modern ages, if you will. Then you have the restoration that takes place, then you have today. That's an awful lot moving around and jarring the earth and impact. Things are stuck into the earth, and moved out, and new buildings over the years. How do you find sites like that when they were made of structures that don't necessarily last, like wood planted into the ground? There were only a few that actually had the brick. That's where the artifacts come in to play.

Lloyd: Post in ground – if I understand correctly, the way you can determine that archaeologically is color. The color of the dirt changes.

Kelly: Soil changes, right.

Lloyd: If you've dug it up to build something new on it, or to put a street across it, you aren't going to have any dirt.

Kelly: Precisely. That's the very thing. If it's been obliterated by all the other activity that's taken place here over the years, what else is there to help you find it?

Lloyd: OK, what else is there to help you?

Kelly: That's what's in this box, in fact. There are two things here we've been looking at now for quite some time. This is referred to as a roofing tile, and this is referred to over here as window leads.

Lloyd: OK, I can figure out what both of those are. Roofing tile is fairly obvious. You need to help me here. Were there glass windowpanes then?

Kelly: There were. That's what this first object is, so it's probably the best place to start. These are pieces of lead here that go to something we call casement windows, which was a pretty common style of window in late 16th, 17th, and even into some early 18th-century sites. Over the years, bits and pieces of these little bits of lead have popped up around the foundation. Basically, the idea is you have pieces of glass, and these pieces of glass have to be retained by these bits of lead within a larger frame of wood or metal.

Back in the '60s, Ivor Noel Hume, along with his conservator, was working with some of these little bits of lead one day from a broken window they had found on a site. They were trying to clean it and conserve the lead, and they happened to notice that on this piece of lead, there were actually some numbers and some letters. Right away they thought, "Well that's odd. Why in the world would you have letters and numbers on a piece of lead that makes up a window?" Well, he very quickly started to realize that these were dates. They were dates most likely of when these windows were manufactured. It became a dating tool for us in many instances on sites.

Lloyd: Oh, OK. Because if I found something that looked like that on the ground, I would just pick it up to see if I could skip it across the nearest creek. It means nothing to me.

Kelly: Right, and that's what I said. It's a really plain sort of object. It also is a perfect example of why we keep everything in archaeology. We don't throw away anything. You never know what something's going to tell you. If Ivor Noel Hume had not kept these things in the past, and he and his conservator had not pursued this, they would not have found this clue for us into the past. So, this is one of the ways in which we're trying to find 17th-century sites.

We have found that, for the most part, 17th-century sites have casement windows. They do move a little bit into the 18th century as well, they were still around for some time. Even if these objects don't have dates on them, by their mere presence, it at least helps us start getting an idea that maybe something else is going on there other than an 18th-century site. It's not a for-certain thing, but it gives us a clue. We wanted to have another object to help us tie it together a little better, and that's where the roofing tiles come in.

Lloyd: Roofing tile, you would not skip that across the creek, because it's too big, and it's heavy.

Kelly: No, that's quite big and quite heavy.

Lloyd: So this is off a roof prior to 1699, maybe?

Kelly: Yes. This one actually comes from a roof from 1662.

Lloyd: So we know when this roof is. I don't know if you know, but I'm curious: where were these tiles made?

Kelly: This one was actually made here. As a little sidebar to some of the research we've done, for most of the tiles that we've come across in the Foundation, we've actually done a fair amount of research on them. We've done X-rays where you can actually look at the core of the material and how it's constructed and what's in it, as well as acid testing where we test with 12 different variables to see if we can match it up to different sites. In fact, we know there was a local maker who was making roofing tiles like this, and distributing them throughout Middle Plantation, even at Jamestown.

Lloyd: So that listening to this, you won't be completely lost, It's a roof tile that's shaped somewhat, is red in color, made of clay, I should suspect.

Kelly: Clay. It's referred to as a pan tile. They overlap eachother on the roof.

Lloyd: I would guess 15 to 16 inches long. Maybe eight, nine inches wide.

Kelly: Thereabouts, yes. That's the standard size.

Lloyd: And heavy. I would imagine if you were working all day laying these on a roof, you would be exhausted by the end of the day.

Kelly: Most likely. And it brings up a good point, too. You wouldn't be able to put something this heavy, with as many as it would require to cover your roof, on an insubstantial structure. In the Middle Plantation period, when we were talking about many of these structures being post in ground, well there were also brick for some of these larger plantations that were popping up. There's a question as to why they were doing that. It would be someone who would have the funds to be able to make these or purchase these to put them on their house. It would also have to be a substantial house that could bear the weight of that.

It could also be viewed as a statement. Someone has moved to this area, and they are here. They are permanently here. They are displaying their wealth, and they're displaying a view of Middle Plantation, that it's becoming something of a mover and a shaker.

Lloyd: I've moved here, and I'm important, therefore this place is important. I like that. I love displays of ego, they're such fun. In a way it's nice to know that people back then had the same sort of egos. How many of these have you found, that you could reasonably say, "There must have been six roofs that had roofing tiles?"

Kelly: We've found a number of sites, actually, throughout the Historic Area. Over six sites, at least, that have had these roofs on them. We have found close to a dozen sites at least where we have a combination of the leads and the tiles found together on a site.

The thing to think about it is, we went into this project originally having an idea where we thought there might be 17th-century sites. We had documentation, we had some drawings and maps. We weren't quite certain. We were hoping that if we had some kind of artifact markers or identifiers to be looking for when we're excavating, that maybe if we found those together that would at least give us an idea of where new sites might be that we've not yet excavated. Or, sites that we didn't realize were potential 17th-century sites before. In fact, maybe they are, and we should be looking at them a little differently as well.

Lloyd: That's going to keep you busy for years.

Kelly: Absolutely.

Lloyd: That’s Colonial Williamsburg: Past & Present this time. Visit history.org to learn more. Check back often, we'll post more for you to download and hear.