Distinguished Visiting Professor Rhys Isaac’s 1970 encounter with Colonial Williamsburg’s Historic Area set the course for his career.

Podcast (audio): Download (3.2MB)

Subscribe: RSS

Transcript

Lloyd Dobyns: Hi! Welcome to Colonial Williamsburg: Past & Present. This is “Behind the Scenes” where you meet the people who work here. That’s my job. I’m Lloyd Dobyns, and mostly I ask questions.

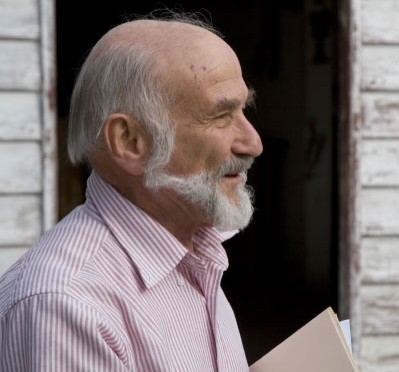

This time, I’m asking Rhys Isaac, who is Distinguished Visiting Professor of Early American History at the College of William and Mary, and winner of the 1983 Pulitzer Prize in History. And for our purposes today, he’s had a long and distinguished association with Colonial Williamsburg, which started when, Rhys?

Rhys Isaac: Well, I came to Williamsburg for the first time in May of 1970. I was just getting into my research in Virginia history, and I guess that started a wonderful kind of reciprocal relationship. Because I was bowled over by the spectacle of the street of restored houses, that kind of presence of the past in this place, and I could walk into buildings I had already been writing scenes from the history as reported in the newspapers and so on.

And I could walk into those buildings and imagine myself back in that time, and that sort of came around, because when I wrote the book that came out of all that, “The Transformation ofVirginia,” which won the Pulitzer Prize, which you mentioned, I was very much inspired, I think, by that experience of Colonial Williamsburg -- by the restoration of Colonial Williamsburg -- to write a book, one of whose main concerns was to recover and to describe the built environment, the settings in which the action of Virginia history happened. And I doubt if I could have had such an inspiration to do that if I hadn’t had this sort of transforming experience myself on the streets in Colonial Williamsburg.

Lloyd: Now, by this time, everybody who’s listening knows that you’re not an American. What would inspire someone with your national background – South African, English, Australian – to write about colonial history?

Rhys: Well that’s right, I was born in South Africa, I had some of my education in England, and I’ve lived in Australia ever since 1963. And it was from Australia that I began this work.

I write about Virginia history because it’s a very big part of the American Revolution, and it’s part of world history. I was actually intent on writing a study of the way the American Revolution triggered off the French Revolution. And I was going to make a particular study of Thomas Jefferson, who was famously, of course, a leading figure in the American Revolution.

But then, as many people know, he went to France as America’s ambassador, and he was very active in consulting with them, and giving advice to the reformers in France in the period leading up to the revolution of 1789. And indeed, he was able to lay articles of the Virginia Declaration of Rights before the national assembly committee that was preparing the French declaration. And some of those articles in the French declaration are taken straight – translated into French – from the Virginia declaration.

So, my project then was to discover Thomas Jefferson in his Virginia origins. So I came to Virginia to do that, and I’ve never got back to France, because Virginia has so absorbed my attention ever since.

Lloyd: (Laughs.) That is a long time to deal with Virginia history. I have read “The Transformation of Virginia: 1740-1790,” and it deals a great deal with ordinary people.

Rhys: That was very much part of, I mean I suppose I was part of a wave of historians who were intent on doing that, an “everybody history.” And so it would be women as well as men, this is coming out of ‘60s,’70s kind of convulsions, and it would deal with the history of everybody -- women as well as men, blacks as well as whites, poor as well as rich.

So that was the ideal, and I guess one of its distinguishing features, though, that undoubtedly was important in its winning the prize, was that I, first of all, became intent on playing the anthropologist to the past. And anthropology, I suppose, has been more intent on dealing with ordinary people than history, in the long haul.

I got to work back in Australia – there’s an important Australian connection -- with a group of like-minded anthropology-oriented historians, and we became a famous little trio, “The Melvin Group of Ethnographic Historians,” and “The Transformation …” is very much a book that comes out of that collaboration, and applied it to Virginia.

Lloyd: I am told, though I haven’t checked this, that because the book is so focused on everybody, everyman, that all the historical interpreters who come here to portray somebody from that period read that book first.

Rhys: Well that’s one of my, I mean, it’s not pure vanity, but it is a great delight that in part of my relationship with Colonial Williamsburg is that that book is, as I say, it got my inspiration to write the book, it had a powerful input from my first and subsequent experiences of Colonial Williamsburg, but it was then as also a great delight that, having written it the way I did, I discovered that it became a kind of handbook for the training of guides and interpreters. And one whom I met a few years ago suddenly discovered who I was, and she said, “Oh, when I was doing my training, everything was ‘Virginia according to Saint Rhys.’” As you can imagine, that was a pleasing comment to get back.

Lloyd: (Laughs.)Yes, that would be. One of the things I noticed, although it may not be terribly important to the people here; my brother and I were trying to figure out why we so much like to travel, but my mother and father did not. And I quoted to him the line you wrote in it that said Virginians would travel great distances if they wanted to assemble for events and things. And he thought that had it pretty well right.

Rhys: Oh, that’s wonderful to hear. That’s right, I mean, one of the things, as soon as I got a focus on the lived-in landscape of 18th-century Virginia: people lived dispersed. And there were broad fields, and a lot of forest left, and they were very sociable, so you had to walk or ride to find company. And they were great at creating occasions for the assembling of people for conviviality.

Lloyd: This is one of those questions that probably is massively unfair, but I don’t mind: Have you thought about the differences from Virginia and the people of the 1800s to Virginia and the people of the 21st century? Are there any giant comparisons that can be safely made, or is that just ridiculous on its face?

Rhys: No, it’s certainly not ridiculous. It would be hard for me to specify ways in which Virginians, as such, are different. Because I guess I see the Virginians I meet, they have a distinctive accent, which I’ve tried to learn to impersonate. But in general, the way I encounter Virginians, they are part of the modern world. They live in an urban world.

So my answer really would come back in terms of, how do modern inhabitants and citizens of a modern democracy – how do they differ from the people whose way of life I was very precisely trying to piece together from the 18th century? And it is, in the great transformation that sort of happened in the world, democracy superceded monarchy in government. And urbanization superceded a pre-industrial way of life.

Which, not many people are sufficiently aware, that there were no workplaces as such in the 18th century. All the work by which production was done in the 18th century happened in somebody’s household. So you didn’t go out to work. Overwhelmingly, people were in agriculture: they worked on the farm. But if they worked in some manufacture, they worked in the blacksmith’s workshop and lived in his house.

So, the scale of the units of organization were much more differently grouped, in a sense, in that world. And if you think about it, that’s a total difference. Not just in government and ideology, but in the organization of life between the 18th century and the 20th, 21st century.

Lloyd: You said earlier that you came to Williamsburg with the French in mind, and Thomas Jefferson in mind, and you never got back to the French because you just got interested in Virginia in the 18th century. Did you ever get back to Jefferson? I don’t remember that you have a Jefferson book.

Rhys: No, I don’t have a Jefferson book. I have an ambition to write one. I’ve written some essays on what I consider to be, in some sense, my discovery that there are two Monticellos. There’s the one that everybody knows that’s on the American nickel, and you can visit now. But that, of course, was the house he rebuilt after he came back from France.

The first Monticello was, to slightly overstate it -- but not much -- it was a kind of temple of married love that he built for his marriage, which he much celebrated, with Martha and the domestic life they enjoyed. And he only consented to go to France because Martha had died. He said, you know, there’s nothing to keep me here now. He had refused the appointment when it was first offered him. So then she died and he left. So there was a first Monticello, and I’ve written an essay about that -- what was happening with the construction of that house, and so on. I do mean to go forward and write the book that needs to be grown from that essay.

So, yes, I still try to keep in step with Jefferson. And there is, in “The Transformation of Virginia,” there is, I hope, an important sort of like a part of a chapter, but an important part of that chapter that looks at Jefferson, and the very important step that he masterminded of the separation of church and state in Virginia. Which set a model for the United States, and in some sense, for the modern democratic world. And so it was a very important outcome of the revolution in Virginia and it had Jefferson’s stamp on it.

Lloyd: What next?

Rhys: Well, there are two things next. And this comes through my association, very active association with Colonial Williamsburg. I am actually not just a professor in the college, I’m a professor in a program that is joint between the college and Colonial Williamsburg, so I actually teach the museum to the college students as a teacher.

But along with that, I am a research associate of Colonial Williamsburg. And the big engagement of that has been to be one of the little steering committee to write “The Big Book of Williamsburg.” It’s called that, as we will do a history of Williamsburg: how it came into being in 1699, how it developed as the center of government and of fashion and commerce in Virginia, and then of course, we look at its kind of demise, in a sense, when the legislature went from here and this became a sleepy backwater. So, I’m an active participant in the writing of that book, and very much enjoying the teamwork that we’re engaged in to get that book written.

Lloyd: When do you think we could look forward to seeing that?

Rhys: I wish I could say next year or the year after next. With Colonial Williamsburg, it’s a strength, and could be seen as a fault: It does things very thoroughly, and that means they’re not done very fast.

Lloyd: (Laughs.) You can have fast, or you can have complete, but you can’t have fast and complete. That sounds very fascinating, that this is a group effort.

Rhys: Yes, and again, that relates to my overwhelming first experience of Colonial Williamsburg. We’re intent that it will be written not just from archival, paper-based records, but all the kinds of records that Colonial Williamsburg exists to display -- the buildings, the archaeology under the ground, all the kind of evidences of what the past was and what is was like --we’re intent on incorporating into that book. And I suppose we hope to make a model book of that kind of comprehensive history.

Lloyd: Well you’ve got to get it finished up, I want to read it.

Lloyd: That’s Colonial Williamsburg: Past & Present this time. Check history.org often. We’ll post more for you to download and hear.