Political parties were new, the losers became Vice Presidents, and negative campaigning was finding its feet in the election of 1796. Professor Jack Lynch has the history.

Podcast (audio): Download (8.5MB)

Subscribe: RSS

Transcript

Harmony Hunter: Hi, welcome to the podcast. I’m Harmony Hunter. As we look ahead to the presidential elections, it’s also a very good time to look back at America’s first presidential elections. Our guest today is Professor Jack Lynch, who’s compiled a brief history of the first elections in an article for the Autumn Colonial Williamsburg Journal. Professor Lynch, thank you for being our guest today.

Jack Lynch: Thanks for having me.

Harmony: Well it’s surprising how many of the customs and assumptions about elections today were really not present at the very founding of the country. When we look at the very first president, of course, George Washington, he was elected unanimously and without thought of any term limit.

Jack: He was elected unanimously. He wasn’t necessarily elected by popular vote. They hadn’t quite worked that out. He didn’t belong to any party. He didn’t campaign. So many things that we take for granted as being a natural part of elections weren’t there at the beginning. It took a while for them to be worked out.

Harmony: The sense I get from reading your article is that we’re coming from a monarchy, and some of those habits are sort of hard to break. So even though we elected a president, we sort of expect him to be in power for a long time.

Jack: Well, the Constitution provides a mechanism for electing a president, but there’s no evidence anyone really thought through how we would have the end of a term of a president. No one thought about a term limit. No one had any provisions for what happens if someone resigns at any time. It just doesn’t seem to have been on their minds. So they probably were thinking in monarchical terms and only when they faced the actual fact of needing a successor did any of these problems come up.

Harmony: And you point out in your article that in fact we didn’t have term limits until the 22nd amendment in 1951, so theoretically up until 1951, a president could stand for election every four years.

Jack: Yes, there was absolutely nothing to stop it other than the precedent established by George Washington, which is that you run for election twice and then that’s the end of your natural term. But there was nothing legal about that until the middle of the 20th century.

Harmony: And let’s talk about that precedent that George Washington set when he steps down and announces his retirement in his farewell address.

Jack: The Farewell Address, I like to point out that it’s got to be one of the most surprising documents to the people who lived through it. This is an age that produced all sorts of documents that were shocking and surprising in various ways and challenged traditional notions. We don’t often think of Washington’s farewell address as being one of those, but to the world of 1796, this seemed utterly shocking that the head of state was choosing not to be head of state anymore. There was no precedent for that sort of thing.

When he did that, he set in motion the election of 1796, which doesn’t get as much attention as the notorious election of 1800, which is famous for its chaos, but in some ways I think it might be more important.

Harmony: So 1796 becomes a very important election because it establishes so many of, or it’s the first time we see so many of these very familiar trappings of elections. We see parties emerge, we see negative campaigning emerge. Talk about some of the things that are firsts that happened in that election after George Washington steps down.

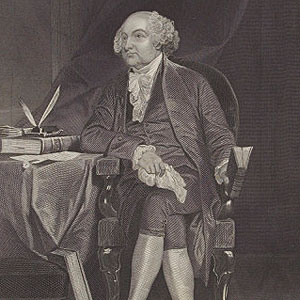

Jack: Sure. Well I’ll start with the things that are still very alien in the election of 1796. For one, the candidates themselves did not campaign. This was Jefferson versus Adams and neither of them made any campaign appearances. That was considered beneath their dignity. There were no party conventions. A lot of the trappings that we associate with elections today still hadn’t been worked out, but we can see an embryo, the very beginning of things like political parties.

Washington did not belong to a party, but by 1796 Adams and Jefferson, even though there was no official affiliation, people recognized them as coming from political parties. There was campaigning. It wasn’t done by the candidates themselves, but they left it to their supporters and often the campaigning was really bitter. There were some positive statements of program, but there were also plenty of bitter attacks on the candidates in the newspapers – makes some of our modern negative campaigning look positively tame by comparison.

Harmony: So when we think it’s bad today we have to remember that that goes back to the very beginning, nearly?

Jack: Nearly to the beginning. Jefferson and Adams certainly did a lot of mudslinging by proxy. Washington, certainly Washington’s first election there wasn’t any negative campaigning. By the middle of his second term there were some pretty bitter attacks even on Saint George Washington. By the time you get to the mid-1790s, oh Lord, they make our negative campaigning look like amateur hour. They were very good at it.

Harmony: And so the first two political parties that really emerge there are the Federalists and the Democratic Republicans. Can we see traces of the DNA of the modern Democratic and Republican parties in those two parties?

Jack: Well it’s always dangerous to try to map parties from 200 years ago onto the parties today. Once we start doing that we start glossing over important differences. But the Federalist party believed in a strong central government. The Democratic Republican party, which we usually just call Republican for short, the Republican party believed in less centrality in the government, more things left up to states and individual jurisdictions.

There were plenty of differences in their attitudes, so to some extent insofar as we imagine the modern left being more associated with the strong central government, at least on what we call domestic issues, and the modern right being more associated with devolution of power to the states. I guess there are some similarities.

Harmony: I wonder if we can surmise that the development of party politics would actually have been a disappointment to Washington, who advised against parties and factions?

Jack: There is nothing about parties in any of our founding documents and this wasn’t so much an oversight on their part as an expression of a conviction that parties were necessarily bad things. The 18th century thought party was the same as faction, and faction meant putting the interests of the few over the interests of the many. So there’s a lot of writing in Britain and in America in the 18th century about parties and about faction, but virtually everyone took it for granted that it was a bad thing. So Washington himself didn’t belong to a party, and Washington himself in his farewell address gives plenty of advice for the young nation, but one of the things he advices is to avoid faction.

Harmony: So we’re up to the election, we’ve got John Adams standing against Thomas Jefferson. There is a lot of mud being thrown. What are some of the allegations against the character or the outlook of both of those candidates? What are people saying about them?

Jack: Well this is during the French Revolution, so that was an important background to the American elections. Jefferson tended to support the cause of the French Revolution, Adams didn’t. Adams was more friendly toward Great Britain. So when the two parties, the nacent parties went at one another, Jefferson was a radical, he was an atheist, he believed in tearing down all systems. He was all in favor of the revolutionary terror.

To hear Jefferson’s supporters describe Adams, he was a monarchist, he did not believe in democracy or freedom. He believed in keeping George III in place. So that was an important background, but once people started these attacks they began to spin out all sorts of fantasies about wild anti-religious beliefs on the part of Jefferson and so on. They often went over the top. It was pretty remarkable.

Harmony: So they finally make it. You say they campaign for seven weeks. They get to the election, and I love the twist at the end of this story which is that Adams, of course, wins, but Thomas Jefferson comes in second, and what’s the implication of coming in second at this point in our Constitution?

Jack: Well, remember before the 12th Amendment to the Constitution, the provision is whoever gets the most votes in the electoral college is president and whoever gets the second most votes in the electoral college is vice president. And this seems to us so obviously absurd. I mean if you think about recent elections the tickets we’d have – we would have the Obama-McCain administration, or we would have the Bush-Kerry administration.

When we think of it in our modern terms it’s such an obviously stupid idea. We can’t imagine why they did it, but if you remember that they thought parties were a bad thing, then it makes a kind of sense. If people don’t represent particular bodies of interest, if they’re not representing particular minorities then, well, it makes sense that the most powerful person should be whoever got the largest number of votes, and the supporter of that should be whoever came in second, because they all share the same interests.

That was the vision of the Founders, that we would all have the same interests in mind and we would simply put our first and second choices in place. Once we had parties, though, it became obvious that would never work and in fact we ended up with a situation where Adams wins a narrow victory over Jefferson. Jefferson from another party becomes Adams’ Vice President and really does not like it one bit.

Harmony: It’s so fascinating and eye opening to look at America first beginning to exercise these provisions that it’s built for itself and we figure out how to run an election, how to run this government that we’ve created and you point out that this is actually the first time in the history of modern democracy that there’s a peaceful transfer of power.

Jack: It is a remarkable thing. We are so accustomed to elections going comparatively smoothly. We’ll set aside out own chaos of the 2000 election as something of a blip, but we’re so accustomed to elections happening and a smooth transition of power from one party to the other that we forget what an oddity that was in historical terms. There was no instance of a large nation having one political interest peacefully hand the reins to its bitterest enemy. Mind you, there were changes of regime in all sorts of countries, but they tended to come either through revolution or through assassinations or something like that. The very fact that this worked is downright astonishing.

Harmony: Professor Lynch, thank you for being our guest today. If you’d like to read more about the election of 1796, look for his article in the Autumn 2012 Colonial Williamsburg Journal titled “A Great Deal of Noise, Whipping and Spurring.” Professor Lynch, thank you for being here today.

Jack: Oh it’s been great talking to you. Thank you.