New questions are raised as old ones are answered in the study of the Frenchman’s Map. Architectural researcher Ed Chappell talks about the document.

Podcast (audio): Download (3.2MB)

Subscribe: RSS

Transcript

Lloyd Dobyns: Hi, welcome to Colonial Williamsburg: Past & Present on history.org. This is "Behind the Scenes" where you meet the people who work here. That's my job. I'm Lloyd Dobyns, and mostly I ask questions.

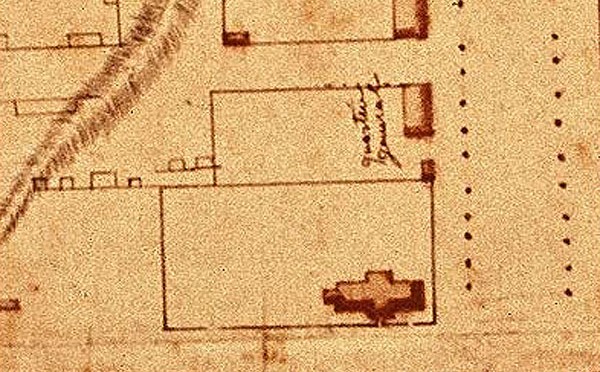

A map was drawn, and then forgotten. For an airless century, it lay tucked in a book, as though holding the page for a reader who would never return. Few documents have been of greater importance to Williamsburg's restoration than this yellowed page, known only as the Frenchman's Map.

Colonial Williamsburg's Ed Chappell, who is Robert's Director of Architectural Research, is here to tell us what that map meant to the men who found it.

It is, in relative terms, I guess a fairly newly-found document compared to when it was prepared. So I don't want to say it's a new document, but it’s sort of newly found.

Ed Chappell: Well I think that's right. There is no early known provenance for this. The first we know is that it was found by a collector in New York, and given to the College of William and Mary, then first focused on with great attention in the late 1920s when the Boston Architects – Perry, Shaw, and Hepburn – worked with W.A. R. Goodwin, John D. Rockefeller, and everyone on the restoration.

It was very useful for them because it sort of captures the town in full glory, in full bloom at the end of the Revolutionary War. So the town suffered some in the Revolutionary period. But it's really the third quarter of the 18th century, the quarter century before the war, that the town fleshes out to the degree that we think of it today. The map captures it at that moment.

Lloyd: The Frenchman's Map is an overhead view looking straight down on the town of Williamsburg as it appeared in 1782. All the buildings are in there, though probably not to scale, I should think. The streets are there and it's all laid out and you know exactly where things are. So if you're trying to restore the town, it's a good reference to go back to and say, "OK, this is here and this is here and this is here, though probably not exactly like this."

Ed: That's right. Sometimes it's remarkably detailed. It's particularly useful when it shows subdivisions of properties with fence lines. Or it shows what appeared to be porches at the fronts of buildings at the east end of Duke of Gloucester Street. Or peculiar little fence lines that open up the street front to the front door. At times it can be remarkably detailed, and then at times it's frustratingly incomplete. It's a grand map.

It's pretty clear that it was never finished. I would say it's about 95 percent finished. There are parts of complexes like Peyton Randolph's site that are largely incomplete. On parts of the map, he shows formally-planted trees, trees planted in a formal pattern, say along Palace Green, along the Custis walk, northeast of the coffeehouse site. But then at other times, he'll leave a large area undefined. It's pretty clear he didn't finish.

Lloyd: You have said "the cartographer" a couple of times. We don't know who he was.

Ed: That's right, that's right. We assume that the person was French, because most of the inscriptions are in French. Although, they're done in a number of hands and there's some English on the drawing.

It really looks like it comes out of the French school of military cartography. European warfare was regularized and developed into sort of a science in the late 17th and 18th century. Part of that kind of professionalization, specialization of the military, was to have the capability to develop these complex plans.

Most of them done by the French army in this region are not this detailed. They tend to show the topography in general terms and the position of the armies, particularly where they're camped. There are a number of them from the Williamsburg area that show this. The streets are sketched out, and usually buildings are not detailed at all. There are a couple of billeting maps, one for Yorktown and another for Hampton. They're clearly meant as maps to define where troops are billeted in existing buildings.

Alan Simpson, who's the historian who has looked most carefully and thoughtfully at the Frenchman's Map suggests, his best guess, is a billeting map. But it obviously includes many features that are of absolutely no use in billeting troops. You don't really care about elaborate fence lines in that case. You don't really care about the shape of a ravine, or the sort of relationship of the topography to the street line, which is all here.

Now, is that simply because a French cartographer is here, has time, and is being French? Perhaps. I think there's no clear answer on precisely what this was intended for.

Lloyd: Mr. Simpson, he suggests that it might have been a billeting map, and he suggests that there were four people who were in Williamsburg at that time who had the training to do that sort of thing and who had the hand for some of the inscription. But no one's ever tried to figure out which of the four it might have been. Or if indeed it might have been a fifth guy that we've never heard of.

Ed: Right, right. Well, I think this is a topic that is one that will be pursued at some point. I would think that the principal way to attack it is to really look very seriously at French holdings of cartography. They are generous, if not vast. They would provide a really, I think in some ways, useful context to understand how this fits into the larger story of French military cartography.

There's some chance that one would find a paper with the same watermarks, notes in the same hand, and possibly an identity. I think like so many topics here, kind of principal stories, fascinating topics that have engaged people at Colonial Williamsburg for 50 years, many of them retain a rich possibility of new research and development.

Lloyd: I don't know, I suppose somebody at Colonial Williamsburg might someday get a grant to go to France for a year and that would be quite pleasant.

Ed: That would be quite charming, and potentially useful.

Lloyd: One of the things I found fascinating was that there is a date on the map, and it's 17 … one, seven, eight; those are clear. You can't make a mistake. The fourth date could be a one, could be a two, or could be a six. I find it fascinating how the research was done to find out what was the correct form in writing in France at that period for the numbers one, two, and six, and the alternative way to write a two is exactly the way it's written on the map.

Ed: Yes. I think Alan Simpson, perhaps the most useful thing that he accomplished was to argue very persuasively that it is 1782. Makes a lot more sense of it.

Lloyd: If it is a billeting map after the siege at Yorktown, when French troops did in fact come to Williamsburg, it makes a certain amount of sense if it's 1782, and no sense at all if it's 1786, and very little if it's 1781 because there were no French troops to be billeted. They were all on their way to Yorktown.

It's, if you read it and you haven't made up your mind yet, there is a lot to say it's a billeting map by a guy who wanted to do more than just draw buildings. He was interested in some features of why the buildings were where they were. That's kind of interesting to me because the guy is going – whoever he was – if it is a billeting map, he's going way further than was required.

Ed: Yes. I think it continues to be useful to us. It was particularly helpful in the 1920s and '30s when the restoration began. People – researchers, designers, historians – were trying to get a handle on the arrangement of the town and the scale of the lots. Particularly before the age of stratigraphic archaeology – the connection between foundations and other sorts of architectural remains and dateable artifacts – were refined.

It was useful to be able to say, well, this building was on this particular spot in 1782. We don't know when it was built, we don't know when it came down, but we know it was here. So in some ways, I think maybe it was more important then than it is now. But it continues to be very useful to us.

Lloyd: We know it's a Frenchman – we think we know it's a Frenchman – who drew the map. Was he a military officer? We think probably. Was he necessarily a military officer? No. You could be an engineer and not be a military officer. I wish he had at least signed the back of it, so we'd know who'd done it.

Ed: Right. Well it's also this intriguing possibility that somewhere out there in the world is another copy. There are interesting prick holes over the map, and there seem to be a couple periods of those. I suspect that, at least once, as a result of production of measuring the buildings and plotlines that it's at least possible that this was done as a rough draft. And that one moved on to a more elaborate map. Or that they're sketches. Who knows, what is there, 10 percent chance there is one out there? Certainly.

Lloyd: I suppose that it could be. I would like to think that if there is a more polished or finished product, that it was better taken care of than being stuck in a book and left for 100 years.

Ed: Well most documents have their ups and downs, like buildings.

Lloyd: One of the things I think about was, "Well, suppose we hadn’t found the Frenchman's Map? Would we still have been able to restore Williamsburg?" Well, maybe. But I think not as well.

Ed: Yeah. Well any restoration is a result of hopefully many pieces of data.

Lloyd: I've always said when it comes to research there are two things that you need: skill and luck. And you need them in about equal quantities.

Ed: That's right. And some hard work.